Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) offer zero-emission driving with fast refueling and long range, but face hurdles like limited infrastructure and high costs. While promising for heavy transport and commercial use, widespread adoption depends on technological advances, policy support, and green hydrogen production scaling up.

Imagine pulling up to a pump, filling your car in under five minutes, and driving 350 miles—all while emitting nothing but clean water vapor. Sounds like science fiction, right? But that’s exactly what hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) promise. As the world races to cut carbon emissions and ditch fossil fuels, hydrogen has emerged as a potential game-changer in clean transportation. But are hydrogen fuel cell vehicles the future—or just a flash in the pan?

You’ve probably heard more about electric vehicles (EVs) powered by batteries. They’re everywhere now—Teslas, Ford Lightnings, and even electric school buses. But hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are quietly gaining attention, especially in industries where battery weight, charging time, and range matter most. From delivery trucks to city buses, hydrogen is being tested as a practical alternative. Yet, despite the buzz, FCEVs still make up less than 0.1% of new car sales globally. So what’s holding them back? And could they still win the clean transport race?

The truth is, hydrogen isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. It has real strengths—especially for long-haul and heavy-duty transport—but also serious challenges, from cost to infrastructure. In this article, we’ll dive deep into whether hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are truly the future, exploring how they work, where they shine, and what needs to happen for them to go mainstream.

Key Takeaways

- Zero tailpipe emissions: FCEVs emit only water vapor, making them environmentally friendly during operation.

- Fast refueling and long range: Unlike battery EVs, hydrogen cars can refuel in minutes and travel 300–400 miles per tank.

- Limited infrastructure: Fewer than 200 hydrogen refueling stations exist in the U.S., mostly in California.

- High production and vehicle costs: Green hydrogen is expensive to produce, and FCEVs remain pricier than EVs or gas cars.

- Best suited for heavy-duty transport: Trucks, buses, and trains benefit more from hydrogen’s energy density and quick refueling.

- Energy efficiency challenges: Hydrogen production and conversion lose more energy than direct battery charging.

- Future depends on green hydrogen: Widespread adoption requires scaling renewable-powered electrolysis to cut emissions and costs.

Quick Answers to Common Questions

How do hydrogen fuel cell vehicles produce electricity?

They use a fuel cell stack to combine hydrogen and oxygen, creating electricity, water, and heat—no combustion involved.

Are hydrogen cars really zero-emission?

Yes, during operation—they only emit water vapor. But emissions depend on how the hydrogen is produced.

Why aren’t there more hydrogen refueling stations?

High costs, low demand, and technical challenges in storing and transporting hydrogen limit station development.

Can I charge a hydrogen car at home?

No—hydrogen must be refueled at specialized stations. Home refueling systems are not yet practical or widely available.

Will hydrogen cars ever be as common as EVs?

Unlikely for passenger cars, but they could dominate in trucks, buses, and other heavy-duty applications.

📑 Table of Contents

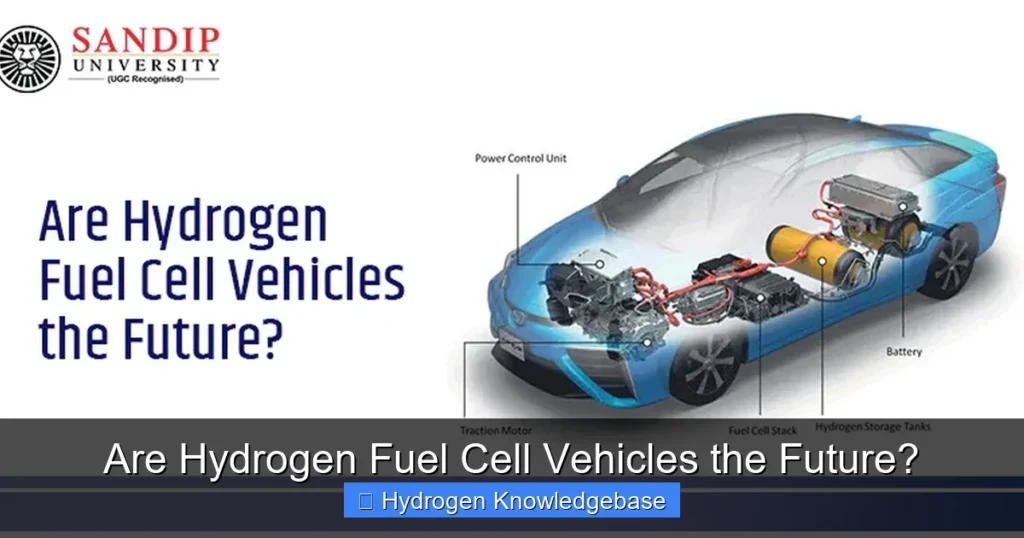

How Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles Work

At first glance, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles might seem like magic. But the science behind them is actually pretty straightforward—and incredibly clean.

The Basics of the Fuel Cell

A hydrogen fuel cell vehicle runs on electricity, just like a battery EV. But instead of storing power in a large battery, it generates electricity on demand using hydrogen gas. Inside the car is a device called a fuel cell stack. This stack combines hydrogen from the onboard tank with oxygen from the air. The chemical reaction produces electricity, water, and a little heat—nothing else.

The electricity powers an electric motor that drives the wheels. The only thing that comes out of the tailpipe? Pure water vapor. No carbon dioxide, no nitrogen oxides, no soot. It’s as clean as it gets during operation.

Refueling vs. Charging

One of the biggest advantages of FCEVs is how they’re refueled. Instead of plugging in and waiting 30 minutes to several hours (even with fast chargers), you fill up with hydrogen gas in about 3 to 5 minutes—just like a gasoline car. That’s a huge win for drivers who need to get back on the road quickly.

For example, the Toyota Mirai, one of the most popular FCEVs, can go from empty to full in under five minutes and travel up to 400 miles. Compare that to a Tesla Model 3, which might take 20–30 minutes at a Supercharger to reach 80% charge—and even less range in cold weather. For long-distance travelers or commercial fleets, that time savings adds up fast.

Energy Storage and Range

Hydrogen is incredibly energy-dense by weight. A small amount of hydrogen holds a lot of energy—about three times more than gasoline by mass. That makes it ideal for vehicles that need to carry heavy loads or travel long distances without frequent stops.

While most battery EVs max out around 250–300 miles per charge, many FCEVs easily exceed 300 miles, with some prototypes pushing past 500. That’s why companies like Hyundai and Nikola are betting big on hydrogen-powered trucks. A Class 8 semi-truck with a battery might need a 1,000-kWh pack—weighing several tons and taking hours to charge. A hydrogen version could match that range with a lighter tank and a 10-minute fill-up.

Environmental Benefits and Challenges

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles sound great on paper—zero emissions, fast refueling, long range. But are they really as green as they seem?

Zero Tailpipe Emissions

Let’s start with the obvious: FCEVs produce no harmful emissions while driving. No CO₂, no particulate matter, no smog-forming pollutants. That’s a massive win for air quality, especially in cities where diesel trucks and buses contribute heavily to pollution.

Visual guide about Are Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles the Future?

Image source: sustainableamerica.org

In places like Los Angeles or Tokyo, where air quality is a major concern, hydrogen buses and taxis are already in use. The only thing coming out of the exhaust is water—literally. Some cities even collect the water vapor and use it to clean windshields or water plants.

The Problem with “Grey” Hydrogen

Here’s the catch: while the car itself is clean, the hydrogen fuel often isn’t. Today, over 95% of hydrogen is produced using natural gas in a process called steam methane reforming. This method releases carbon dioxide—lots of it. In fact, producing one kilogram of “grey” hydrogen can emit up to 12 kg of CO₂.

So if your hydrogen comes from fossil fuels, the environmental benefit shrinks dramatically. It’s like driving an EV powered entirely by coal. The car is clean, but the energy source isn’t.

The Promise of Green Hydrogen

The real future of clean hydrogen lies in “green” hydrogen—produced using renewable energy like wind or solar to power electrolysis. Electrolysis splits water (H₂O) into hydrogen and oxygen, with no emissions if the electricity is clean.

Green hydrogen is still expensive—about $4–6 per kilogram, compared to $1–2 for grey hydrogen. But costs are falling fast. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), green hydrogen could drop below $2/kg by 2030 if renewable energy prices keep falling and electrolyzer production scales up.

Countries like Germany, Japan, and Australia are investing billions in green hydrogen projects. For example, Australia’s Asian Renewable Energy Hub plans to produce hydrogen using 26 gigawatts of wind and solar—enough to power millions of vehicles.

Energy Efficiency: A Hidden Drawback

Even with green hydrogen, FCEVs aren’t the most energy-efficient option. Here’s why: producing hydrogen, compressing it, transporting it, and converting it back to electricity in the fuel cell loses a lot of energy—up to 60% from source to wheel.

In contrast, battery EVs use about 77% of the energy from the grid to power the wheels. That’s a big difference. So while hydrogen can be clean, it’s not the most efficient way to use renewable energy.

That’s why many experts argue that hydrogen should be reserved for applications where batteries struggle—like aviation, shipping, and heavy freight—rather than passenger cars.

Current State of Hydrogen Infrastructure

You can have the cleanest car in the world, but if you can’t refuel it, it’s useless. And right now, hydrogen infrastructure is one of the biggest roadblocks.

Limited Refueling Stations

As of 2024, there are fewer than 200 hydrogen refueling stations in the United States—and over 80% are in California. That means if you live in Texas, New York, or Florida, you’re out of luck. Even in California, stations are clustered around major cities like Los Angeles and San Francisco.

Compare that to over 150,000 gas stations nationwide or more than 60,000 public EV chargers. The gap is enormous. Without a reliable network, consumers simply won’t buy FCEVs—no matter how clean or fast they are.

High Costs of Building Stations

Building a hydrogen station isn’t cheap. A single station can cost $1–3 million, depending on size and technology. That’s 10 to 30 times more than a fast EV charger. And because demand is low, few companies are willing to invest.

Hydrogen is also tricky to store and transport. It’s a tiny, leak-prone molecule that requires high-pressure tanks or cryogenic cooling. That adds complexity and cost to the supply chain.

Progress and Pilot Projects

Despite the challenges, progress is being made. California has committed $20 million a year to expand its hydrogen network, with a goal of 200 stations by 2025. Japan has over 160 stations and aims for 1,000 by 2030. Germany is building a national hydrogen highway with support from the EU.

Private companies are also stepping in. Shell, Air Liquide, and Toyota are partnering on hydrogen hubs in California and Europe. In 2023, Hyundai launched a hydrogen-powered truck fleet in Switzerland, supported by a network of refueling stations along major freight routes.

These pilot projects show that with the right investment and policy support, hydrogen infrastructure can grow—but it will take time and coordination.

Hydrogen vs. Battery Electric Vehicles

The big question isn’t just whether hydrogen works—it’s whether it’s better than what we already have. And that means comparing FCEVs to battery electric vehicles (BEVs).

Refueling Time and Range

This is where hydrogen shines. A 5-minute fill-up and 300+ mile range beat most BEVs hands down. For long-haul trucking, delivery vans, or ride-sharing fleets, that’s a game-changer. Imagine a UPS truck that can run all day without stopping for hours to charge.

But for daily commuting? Most people drive less than 40 miles a day. For that, a 200-mile EV is more than enough—and you can charge at home overnight for pennies.

Cost and Affordability

Right now, FCEVs are expensive. The Toyota Mirai starts around $50,000, and the Hyundai NEXO is similar. That’s before any incentives. In contrast, many EVs—like the Chevy Bolt or Tesla Model 3—start under $40,000, with tax credits bringing them even lower.

Hydrogen fuel is also pricey. In California, it costs about $16 per kilogram. A Mirai uses about 1 kg per 60–70 miles, so a full tank (about 5 kg) costs $80 and gets you 300–350 miles. That’s roughly double the cost per mile of electricity for an EV.

Environmental Impact

If hydrogen comes from renewables, FCEVs can be very clean. But as we’ve seen, most hydrogen today is grey—so BEVs often have a lower carbon footprint, especially if charged with clean energy.

Over time, as green hydrogen scales, this could change. But for now, BEVs are the more sustainable choice for most drivers.

Vehicle Weight and Space

Battery packs are heavy. A large EV battery can weigh over 1,000 pounds. That’s fine for a passenger car, but for trucks or buses, it reduces payload and efficiency.

Hydrogen tanks are lighter and take up less space. That’s why hydrogen is being explored for aviation and shipping, where every pound counts. Airbus, for example, is developing hydrogen-powered planes for 2035.

Real-World Applications and Success Stories

While passenger FCEVs are still niche, hydrogen is finding real success in other areas.

Heavy-Duty Trucks and Freight

Companies like Nikola, Hyundai, and Toyota are developing hydrogen-powered semi-trucks. These vehicles need long range, fast refueling, and high payload—exactly where hydrogen excels.

In 2023, Hyundai delivered 48 hydrogen trucks to Switzerland, where they’re used for regional freight. The trucks refuel in 15 minutes and have a range of over 250 miles. Similar projects are underway in Germany, the U.S., and South Korea.

Public Transit and Buses

Cities around the world are testing hydrogen buses. London, Berlin, and Tokyo all have hydrogen bus fleets. These buses reduce urban pollution and can refuel quickly at central depots.

In California, the Orange County Transportation Authority runs hydrogen buses that serve over 100,000 passengers a month—with zero emissions.

Trains and Maritime Transport

Hydrogen is also being used in trains. Germany’s Coradia iLint is the world’s first hydrogen-powered passenger train, running on routes where electrification isn’t feasible.

In shipping, companies like Maersk and CMA CGM are exploring hydrogen and ammonia (a hydrogen carrier) as clean fuels for cargo ships. These vessels travel long distances and can’t rely on batteries.

The Road Ahead: Can Hydrogen Win?

So, are hydrogen fuel cell vehicles the future? The answer isn’t a simple yes or no.

Hydrogen has a clear role—especially in heavy transport, aviation, and industries where batteries fall short. But for everyday passenger cars, battery EVs are currently more practical, affordable, and efficient.

The future of hydrogen depends on three things: scaling green hydrogen production, building out refueling infrastructure, and reducing costs. With strong policy support, international cooperation, and technological innovation, hydrogen could become a key part of the clean energy transition.

But it won’t replace batteries—it will complement them. The future of clean transport isn’t one technology; it’s a mix. And hydrogen, with its unique strengths, has a place in that mix.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle?

A hydrogen fuel cell vehicle (FCEV) is an electric car that generates its own electricity using hydrogen gas and oxygen. It emits only water vapor and no harmful pollutants during operation.

How long does it take to refuel a hydrogen car?

Refueling takes about 3 to 5 minutes, similar to filling a gasoline car. This is much faster than charging a battery EV.

Is hydrogen fuel safe?

Yes, hydrogen is safe when handled properly. It’s lighter than air and disperses quickly if leaked. Modern FCEVs have multiple safety systems to prevent accidents.

Why is hydrogen fuel so expensive?

Production, compression, and transportation costs are high. Green hydrogen, made with renewable energy, is especially costly but expected to drop in price.

Can hydrogen be produced sustainably?

Yes, through electrolysis powered by wind, solar, or hydroelectric energy. This “green hydrogen” produces no carbon emissions.

Which companies make hydrogen fuel cell vehicles?

Toyota (Mirai), Hyundai (NEXO), and Honda (Clarity) are the main automakers producing FCEVs for consumers. Several companies also make hydrogen trucks and buses.