Hydrogen fuel cells are made through a precise process involving advanced materials, membrane assembly, and quality control. This clean energy technology converts hydrogen and oxygen into electricity, water, and heat—offering a sustainable alternative to fossil fuels.

Key Takeaways

- Hydrogen fuel cells rely on electrochemical reactions: They generate electricity by combining hydrogen and oxygen, producing only water and heat as byproducts.

- The core component is the membrane electrode assembly (MEA): This includes the proton exchange membrane, catalyst layers, and gas diffusion layers, all working together to facilitate the reaction.

- Platinum-based catalysts are commonly used: Though expensive, they efficiently speed up the reaction; researchers are developing alternatives to reduce costs.

- Manufacturing requires precision and clean environments: Dust or contamination can ruin performance, so production occurs in controlled, cleanroom-like settings.

- Fuel cells are modular and scalable: Multiple cells can be stacked to increase power output for vehicles, buildings, or industrial applications.

- Quality testing is critical: Each cell undergoes rigorous performance and durability checks before being deployed.

- Innovation is driving down costs and improving efficiency: Advances in materials science and manufacturing are making hydrogen fuel cells more accessible and practical.

📑 Table of Contents

Introduction to Hydrogen Fuel Cells

Imagine a world where cars run on water, factories operate without smoke, and homes are powered by clean energy—no emissions, no pollution, just quiet, efficient electricity. That’s the promise of hydrogen fuel cells, a revolutionary technology that’s been quietly advancing for decades and is now stepping into the spotlight as a key player in the clean energy transition.

At their core, hydrogen fuel cells are devices that convert chemical energy into electrical energy through a clean electrochemical process. Unlike batteries, which store energy, fuel cells generate electricity as long as they have a supply of hydrogen and oxygen. The only byproducts? Water and a little heat. This makes them incredibly attractive for reducing greenhouse gas emissions, especially in transportation, backup power systems, and even aerospace applications.

But how exactly are these futuristic power sources made? The process is a blend of chemistry, engineering, and precision manufacturing. From selecting the right materials to assembling delicate components in dust-free environments, every step matters. In this article, we’ll take you behind the scenes to explore the fascinating journey of how hydrogen fuel cells are made—from raw materials to finished products ready to power the future.

The Science Behind Hydrogen Fuel Cells

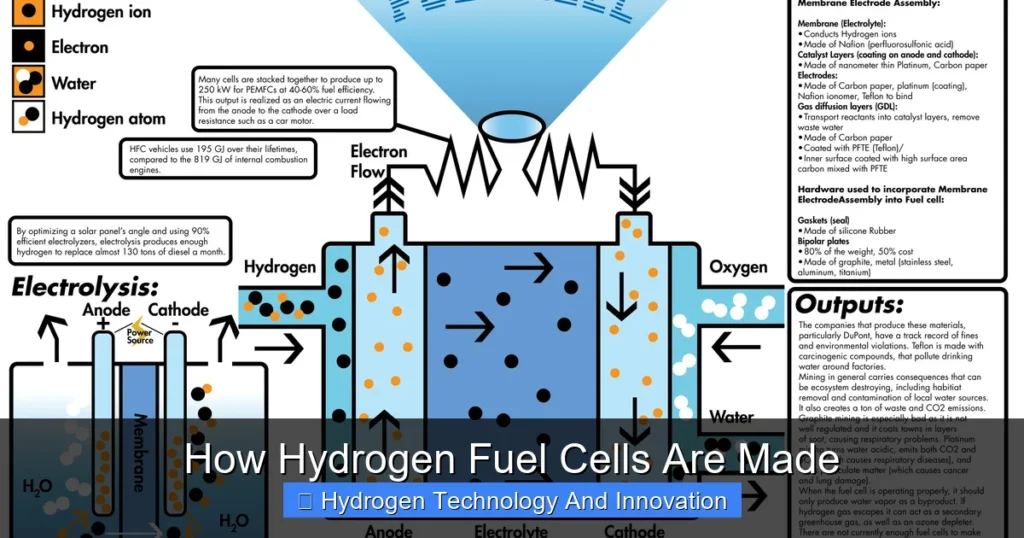

Visual guide about How Hydrogen Fuel Cells Are Made

Image source: sustainablepowernews.com

Before diving into the manufacturing process, it’s important to understand how hydrogen fuel cells work. This foundational knowledge helps explain why certain materials and techniques are essential during production.

At the heart of every hydrogen fuel cell is an electrochemical reaction. Hydrogen gas (H₂) is fed into the anode side of the cell, while oxygen (from the air) enters the cathode side. The anode is coated with a catalyst—usually platinum—that splits the hydrogen molecules into protons and electrons. The protons travel through a special membrane to the cathode, while the electrons are forced to travel through an external circuit, creating an electric current that can power devices.

On the cathode side, the protons, electrons, and oxygen combine to form water (H₂O), which is released as a harmless byproduct. This entire process happens without combustion, making it far cleaner than burning fossil fuels.

There are several types of hydrogen fuel cells, but the most common and widely used is the Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC). It operates at relatively low temperatures (60–80°C), starts quickly, and is ideal for vehicles and portable power systems. Other types include Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFCs), which operate at high temperatures and are better suited for stationary power generation.

Understanding this science is crucial because every step in manufacturing is designed to optimize this reaction. The materials must conduct electricity, resist corrosion, and allow gases to flow freely—all while maintaining structural integrity over thousands of hours of use.

Core Components of a Hydrogen Fuel Cell

A hydrogen fuel cell may seem simple in concept, but it’s made up of several精密 components that must work in perfect harmony. Let’s break down the key parts and their roles.

Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA)

The MEA is the heart of the fuel cell. It’s a sandwich-like structure that includes three critical layers: the proton exchange membrane (PEM), the anode catalyst layer, and the cathode catalyst layer.

The PEM is a thin, polymer-based film that allows only protons (positively charged hydrogen ions) to pass through while blocking electrons. This selective permeability is what forces electrons to travel through an external circuit, generating electricity. The most commonly used PEM material is Nafion, a fluoropolymer developed by DuPont.

The catalyst layers are where the magic happens. The anode catalyst splits hydrogen into protons and electrons, while the cathode catalyst helps combine protons, electrons, and oxygen to form water. Platinum is the go-to catalyst because of its high efficiency, but it’s also expensive and scarce. Researchers are actively working on alternatives like platinum alloys, non-precious metals, and even carbon-based catalysts to reduce costs.

Gas Diffusion Layers (GDLs)

Sandwiched on either side of the MEA are the gas diffusion layers. These porous carbon-based materials allow hydrogen and oxygen to spread evenly across the catalyst layers while also conducting electrons and removing water produced during the reaction.

GDLs must balance several functions: they need to be conductive, permeable to gases, and hydrophobic (water-repelling) to prevent flooding, which can block gas flow and reduce performance. They’re typically made from carbon paper or carbon cloth, treated with a hydrophobic coating like polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE).

Bipolar Plates

On the outer sides of the GDLs are the bipolar plates. These plates serve multiple purposes: they distribute gases to the electrodes, conduct electricity between adjacent cells, remove heat, and provide structural support.

Bipolar plates can be made from graphite, metals (like stainless steel or titanium), or composites. Graphite plates offer excellent conductivity and corrosion resistance but are brittle and expensive to machine. Metal plates are stronger and cheaper but require coatings to prevent corrosion. Composite plates aim to combine the best of both worlds.

Each plate has flow channels etched or stamped into its surface. These channels guide hydrogen and oxygen to the GDLs, ensuring even distribution and efficient reaction. The design of these channels—whether serpentine, parallel, or interdigitated—can significantly impact performance.

Seals and Gaskets

To keep gases contained and prevent leaks, seals and gaskets are placed around the edges of each component. These are typically made from silicone, fluorocarbon, or other elastomers that can withstand the operating conditions and remain flexible over time.

Even tiny leaks can reduce efficiency or create safety hazards, so precision in sealing is critical. Automated dispensing systems are often used to apply sealants with consistent thickness and placement.

Step-by-Step Manufacturing Process

Now that we know the components, let’s walk through how hydrogen fuel cells are actually made. The process is highly technical and requires strict quality control at every stage.

1. Material Preparation and Cleaning

Manufacturing begins with sourcing and preparing raw materials. The proton exchange membrane, carbon paper for GDLs, catalyst inks, and plate materials must all meet exact specifications. Any impurities or inconsistencies can lead to poor performance or early failure.

Before assembly, all components are thoroughly cleaned using solvents or plasma treatment to remove dust, oils, and other contaminants. Even a speck of dirt can interfere with the electrochemical reaction, so cleanliness is non-negotiable.

2. Catalyst Coating

The next step is applying the catalyst to the membrane or GDL. This is typically done using a process called “ink coating.” A catalyst ink—a mixture of platinum nanoparticles, carbon support, ionomer (a polymer similar to the PEM), and solvents—is spread evenly over the surface.

Techniques like spray coating, screen printing, or slot-die coating are used, depending on the desired thickness and precision. The coated material is then dried in a controlled environment to evaporate solvents and form a uniform catalyst layer.

Some manufacturers use a decal transfer method, where the catalyst is first coated onto a transfer film and then heat-pressed onto the membrane. This allows for better control and reduces waste.

3. Membrane Electrode Assembly (MEA) Fabrication

Once the catalyst layers are ready, they are bonded to the proton exchange membrane. This is usually done using a hot-pressing technique, where heat and pressure are applied to fuse the layers together.

The result is a single, integrated MEA that’s about as thick as a sheet of paper but packed with functionality. The MEA must be handled carefully to avoid wrinkles, tears, or contamination.

4. Gas Diffusion Layer Integration

Next, the GDLs are placed on either side of the MEA. They’re aligned precisely and sometimes bonded using light pressure or adhesives. The GDLs must make good contact with the catalyst layers to ensure efficient electron transfer and gas diffusion.

Some manufacturers use a “five-layer MEA,” where the GDLs are pre-bonded to the catalyst layers before final assembly. This can improve consistency and reduce handling errors.

5. Bipolar Plate Assembly

With the MEA and GDLs ready, the bipolar plates are added. Each plate is positioned on either side of the MEA-GDL sandwich, with flow channels facing inward.

Seals or gaskets are applied to the edges of the plates to create a gas-tight seal. Automated dispensing systems ensure consistent application, and vision systems may be used to verify placement.

6. Stacking and Compression

For most applications, a single fuel cell doesn’t produce enough voltage. That’s why multiple cells are stacked together in a “fuel cell stack.” Each cell is separated by a bipolar plate, which also serves as the anode for one cell and the cathode for the next.

The stack is compressed using end plates and tie rods or clamps. The compression must be uniform to ensure good electrical contact and prevent leaks, but not so tight that it damages the delicate MEA.

The number of cells in a stack depends on the desired power output. A small portable generator might use 10–20 cells, while a hydrogen-powered bus could have over 300.

7. Final Assembly and Integration

Once the stack is assembled, it’s integrated into a housing that includes gas inlets and outlets, electrical connections, and cooling channels. Cooling is essential because even though PEM fuel cells run at low temperatures, heat buildup can degrade performance.

Sensors and control systems are added to monitor temperature, pressure, humidity, and voltage. These systems help optimize performance and protect the fuel cell from damage.

Quality Control and Testing

Making a hydrogen fuel cell isn’t just about assembling parts—it’s about ensuring each unit performs reliably under real-world conditions. That’s why rigorous testing is a critical part of the manufacturing process.

Leak Testing

Before any electrical testing, the fuel cell stack undergoes leak testing. Hydrogen is flammable, so even small leaks can be dangerous. Helium or nitrogen is often used as a tracer gas to detect leaks in seals and joints.

Performance Testing

The stack is then connected to a test station that simulates real operating conditions. Hydrogen and air are supplied at controlled rates, and the electrical output is measured across a range of loads.

Key performance metrics include:

– Open-circuit voltage (OCV): The voltage when no current is drawn.

– Polarization curve: Shows how voltage drops as current increases.

– Power density: Watts per square centimeter of active area.

– Efficiency: How much of the hydrogen’s energy is converted to electricity.

Durability and Stress Testing

Fuel cells must last thousands of hours. To test longevity, manufacturers run accelerated stress tests that simulate years of use in a matter of weeks. These tests include:

– Thermal cycling: Repeated heating and cooling to check for material fatigue.

– Load cycling: Rapid changes in power demand to mimic real driving conditions.

– Humidity cycling: Alternating between dry and wet conditions to test membrane durability.

Environmental Testing

Fuel cells are also tested under extreme conditions—high altitude, freezing temperatures, or high humidity—to ensure they work in diverse environments.

Only after passing all these tests is a fuel cell approved for use. Any units that fail are analyzed to identify manufacturing flaws and improve the process.

Challenges in Hydrogen Fuel Cell Manufacturing

Despite the progress, making hydrogen fuel cells at scale remains challenging. Several hurdles must be overcome to make the technology more affordable and widespread.

Cost of Materials

Platinum is one of the biggest cost drivers. While it’s highly effective, it’s also rare and expensive—currently over $30,000 per kilogram. Researchers are exploring ways to reduce platinum loading or replace it entirely with cheaper catalysts like iron-nitrogen-carbon (Fe-N-C) materials.

The proton exchange membrane is another cost factor. Nafion is effective but pricey. Alternatives like sulfonated polyether ether ketone (SPEEK) are being studied, though they often have lower conductivity or durability.

Manufacturing Precision

Fuel cells require micron-level precision. Uneven catalyst coatings, misaligned layers, or inconsistent compression can lead to hot spots, reduced efficiency, or premature failure. This demands advanced equipment and skilled technicians.

Scalability

While small-scale production is feasible, scaling up to mass production—like what’s needed for the automotive industry—is complex. Automated assembly lines are being developed, but they must balance speed with precision.

Supply Chain and Sustainability

The supply of critical materials like platinum and fluoropolymers is limited and concentrated in a few countries. There are also environmental concerns around mining and disposal. Recycling programs for used fuel cells are still in early stages.

Future Innovations and Trends

The future of hydrogen fuel cell manufacturing is bright, thanks to ongoing research and innovation.

Advanced Materials

Scientists are developing new catalysts that use less or no platinum. For example, researchers at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) have created a cobalt-based catalyst that performs nearly as well as platinum. Others are exploring nanostructured materials and single-atom catalysts for higher efficiency.

New membrane materials with higher proton conductivity and better water management are also in development. These could allow fuel cells to operate at higher temperatures or in drier conditions, expanding their applications.

Additive Manufacturing (3D Printing)

3D printing is opening new possibilities for fuel cell design. Complex flow channels, lightweight structures, and integrated components can be printed in a single step, reducing assembly time and material waste.

Companies like Scribble and Additive Manufacturing Customized Machines (AMCM) are already using 3D printing to produce bipolar plates and other parts.

Automation and AI

Artificial intelligence is being used to optimize manufacturing processes. Machine learning algorithms can analyze test data to predict failures, improve coating uniformity, and reduce defects.

Robotic assembly systems are also becoming more common, especially in high-volume production. These systems can handle delicate components with precision and consistency.

Green Hydrogen Integration

As green hydrogen—produced using renewable energy—becomes more available, the entire fuel cell ecosystem is becoming more sustainable. This creates a virtuous cycle: cleaner hydrogen leads to cleaner fuel cells, which in turn support more renewable energy adoption.

Conclusion

Hydrogen fuel cells represent a clean, efficient, and versatile energy solution with the potential to transform industries from transportation to power generation. While the technology has been around for decades, it’s only now reaching the maturity needed for widespread adoption.

The process of making hydrogen fuel cells is a marvel of modern engineering—combining advanced materials,精密 manufacturing, and rigorous testing. From the delicate membrane electrode assembly to the robust bipolar plates, every component plays a vital role in converting hydrogen into usable electricity.

Despite challenges like cost, scalability, and material scarcity, innovation is driving rapid progress. New catalysts, 3D printing, and automation are making fuel cells more affordable and reliable. As green hydrogen production scales up, the dream of a zero-emission energy future becomes more tangible.

Whether you’re a scientist, engineer, policymaker, or just someone curious about clean energy, understanding how hydrogen fuel cells are made offers valuable insight into one of the most promising technologies of our time. The journey from raw materials to a working fuel cell stack is complex, but the payoff—clean, quiet, and sustainable power—is worth every effort.

Frequently Asked Questions

What are hydrogen fuel cells made of?

Hydrogen fuel cells are made of several key components: a proton exchange membrane (PEM), catalyst layers (usually platinum-based), gas diffusion layers (carbon paper or cloth), and bipolar plates (graphite, metal, or composite). These parts work together to convert hydrogen and oxygen into electricity, water, and heat.

How long does it take to manufacture a hydrogen fuel cell?

The manufacturing time varies depending on the scale and complexity, but a single fuel cell stack can take several hours to assemble, including coating, pressing, stacking, and testing. Mass production with automation can reduce this time significantly.

Why are platinum catalysts used in fuel cells?

Platinum is used because it efficiently speeds up the electrochemical reactions at the anode and cathode. It’s highly conductive and stable under operating conditions, though researchers are developing cheaper alternatives to reduce costs.

Can hydrogen fuel cells be recycled?

Yes, many components of hydrogen fuel cells—especially platinum and carbon materials—can be recycled. However, recycling infrastructure is still developing, and more standardized processes are needed to make it economically viable.

Are hydrogen fuel cells safe to manufacture?

Yes, with proper safety protocols. Hydrogen is flammable, so manufacturers use leak detection systems, ventilation, and explosion-proof equipment. Cleanroom environments and automated handling also reduce risks to workers.

What industries use hydrogen fuel cells?

Hydrogen fuel cells are used in transportation (cars, buses, trucks, trains), backup power systems, portable generators, aerospace, and marine applications. They’re also being explored for use in buildings and industrial processes.