Hydrogen vehicles are emerging as a powerful solution in the global shift toward clean energy. By producing only water as emissions and offering quick refueling, they complement electric vehicles in decarbonizing transport and supporting a sustainable energy future.

The world is in the middle of a major energy shift. Fossil fuels, which have powered our economies for over a century, are being phased out in favor of cleaner, more sustainable alternatives. From solar panels to wind turbines, renewable energy sources are becoming the backbone of modern power systems. But one challenge remains: how do we decarbonize sectors that are hard to electrify, like long-haul trucking, aviation, and heavy industry? That’s where hydrogen vehicles come in.

Hydrogen vehicles—particularly fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs)—are gaining attention as a promising part of the clean energy puzzle. Unlike traditional gasoline cars, they don’t burn fuel. Instead, they use hydrogen gas and oxygen from the air to generate electricity through a chemical reaction in a fuel cell. The only byproduct? Pure water. This makes them a zero-emission option that could play a vital role in reducing transportation’s carbon footprint.

But hydrogen isn’t a silver bullet. It comes with challenges—high production costs, limited infrastructure, and questions about efficiency. Still, as technology improves and governments invest in clean energy, hydrogen vehicles are moving from the fringe to the mainstream. Whether you’re a driver, a policymaker, or just someone curious about the future of transportation, understanding hydrogen’s role in the energy transition is essential.

Key Takeaways

- Zero tailpipe emissions: Hydrogen vehicles emit only water vapor, making them ideal for reducing urban air pollution and greenhouse gases.

- Fast refueling and long range: Unlike battery-electric vehicles, hydrogen cars can be refueled in minutes and travel 300–400 miles on a single tank.

- Complementary to battery EVs: Hydrogen excels in heavy-duty transport, aviation, and shipping—sectors where batteries face limitations.

- Green hydrogen is key: For true sustainability, hydrogen must be produced using renewable energy (green hydrogen), not fossil fuels.

- Infrastructure challenges remain: Limited refueling stations and high production costs currently hinder widespread adoption.

- Government and industry support growing: Countries like Japan, Germany, and South Korea are investing heavily in hydrogen infrastructure and vehicle development.

- Future potential in energy storage: Excess renewable energy can be stored as hydrogen, helping balance the grid and support energy transition goals.

📑 Table of Contents

What Are Hydrogen Vehicles?

Hydrogen vehicles are a type of zero-emission vehicle that uses hydrogen gas as their primary fuel source. There are two main types: hydrogen internal combustion engines (H2ICE) and fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs). While H2ICE vehicles burn hydrogen in a modified engine—similar to how gasoline engines work—FCEVs are far more common and efficient.

In a fuel cell vehicle, hydrogen is stored in high-pressure tanks and fed into a fuel cell stack. Inside the stack, hydrogen molecules are split into protons and electrons. The protons pass through a membrane, while the electrons create an electric current that powers the vehicle’s motor. When the protons and electrons reunite with oxygen from the air, they form water—emitted as vapor from the tailpipe. No combustion, no pollution.

The most well-known hydrogen vehicle on the market today is the Toyota Mirai. Launched in 2014, it offers a driving range of over 400 miles and can be refueled in under five minutes—something no battery-electric vehicle (BEV) can match. Hyundai’s NEXO and the Honda Clarity Fuel Cell are other examples, though availability is still limited to select regions.

One of the biggest advantages of hydrogen vehicles is their versatility. They can be used in passenger cars, buses, trucks, trains, and even ships. For example, Alstom’s Coradia iLint is a hydrogen-powered train operating in Germany, replacing diesel trains on non-electrified rail lines. In California, hydrogen fuel cell buses are being tested in public transit systems to reduce emissions in urban areas.

How Do Hydrogen Fuel Cells Work?

At the heart of every hydrogen vehicle is the fuel cell—a device that converts chemical energy into electricity. The most common type used in vehicles is the proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cell.

Here’s how it works in simple terms:

– Hydrogen gas (H₂) enters the fuel cell at the anode (negative side).

– A catalyst—usually platinum—splits the hydrogen molecules into protons and electrons.

– The protons move through the membrane to the cathode (positive side), while the electrons are forced to travel through an external circuit, creating an electric current.

– At the cathode, the electrons and protons combine with oxygen (O₂) from the air to form water (H₂O).

This process is silent, efficient, and produces no harmful emissions. The electricity generated powers the vehicle’s motor, just like in a battery-electric car. The only difference is that the energy source—hydrogen—is stored on board and replenished at a refueling station.

Fuel cells are modular, meaning multiple cells can be stacked together to increase power output. A typical passenger vehicle might use a stack of 300–400 individual cells. The efficiency of a fuel cell is around 60%, which is significantly higher than the 20–30% efficiency of internal combustion engines.

Types of Hydrogen Vehicles

Not all hydrogen vehicles are the same. They vary by application, design, and fuel source. Here are the main categories:

– Passenger Cars: These are the most visible hydrogen vehicles, like the Toyota Mirai and Hyundai NEXO. They’re designed for everyday use, with comfort, safety, and performance comparable to conventional cars.

– Commercial Vehicles: Heavy-duty trucks, delivery vans, and buses benefit greatly from hydrogen. Companies like Nikola and Kenworth are developing hydrogen-powered trucks for long-haul freight. Refueling time and range make hydrogen ideal for logistics.

– Public Transit: Cities are testing hydrogen buses to reduce emissions. For example, London has deployed hydrogen double-decker buses, and cities in China and South Korea are expanding their fleets.

– Rail and Maritime: Trains and ships face unique challenges in electrification due to weight and range. Hydrogen offers a viable alternative. The Coradia iLint train in Germany and the Energy Observer catamaran—powered entirely by hydrogen—are pioneering examples.

– Aviation and Drones: While still in early stages, hydrogen is being explored for aircraft. Airbus aims to launch a hydrogen-powered commercial plane by 2035. Drones using hydrogen fuel cells can fly longer than battery-powered models.

Each of these applications leverages hydrogen’s strengths: high energy density, fast refueling, and zero emissions at the point of use.

Hydrogen Production: Green, Blue, and Grey

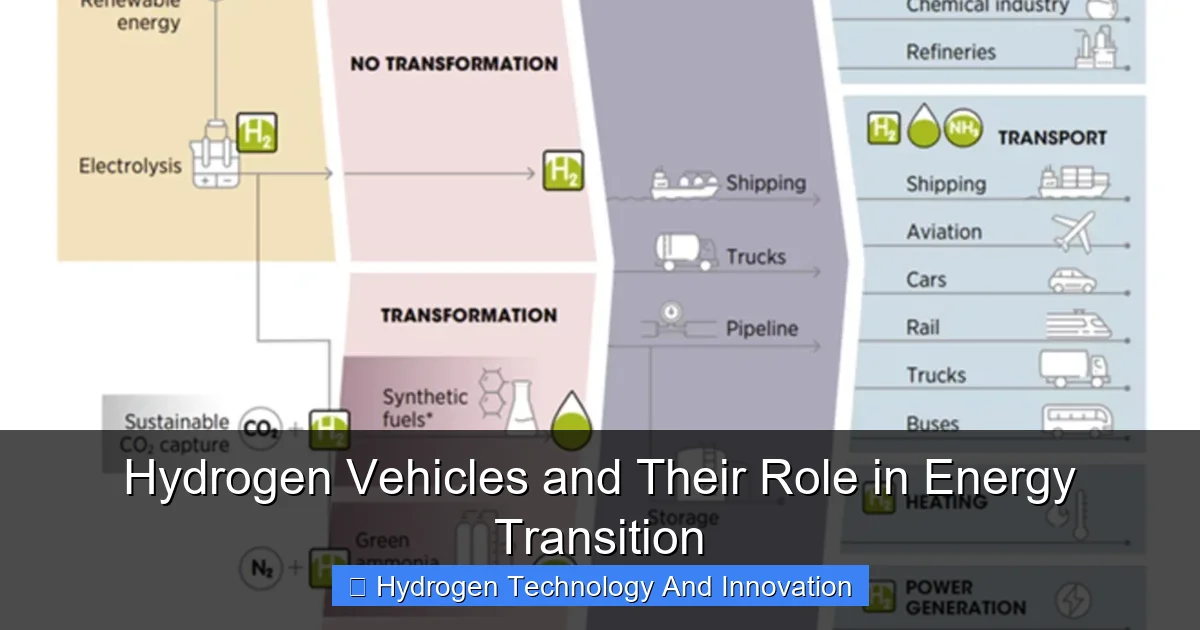

Visual guide about Hydrogen Vehicles and Their Role in Energy Transition

Image source: daily.fattail.com.au

To understand the true environmental impact of hydrogen vehicles, we need to look at how hydrogen is made. Not all hydrogen is created equal. The color-coded system helps distinguish between different production methods:

– Grey Hydrogen: This is the most common and cheapest form, produced from natural gas through a process called steam methane reforming (SMR). It emits large amounts of CO₂—about 10 kg of CO₂ per kg of hydrogen. While it powers some current hydrogen vehicles, it undermines climate goals.

– Blue Hydrogen: Similar to grey hydrogen, but the CO₂ emissions are captured and stored underground (carbon capture and storage, or CCS). This reduces emissions by up to 90%, making it a transitional option. However, it still relies on fossil fuels.

– Green Hydrogen: Produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electrolysis, powered entirely by renewable energy (solar, wind, hydro). This is the only truly sustainable method. It’s currently more expensive, but costs are falling as renewable energy becomes cheaper and electrolyzer technology improves.

For hydrogen vehicles to play a meaningful role in the energy transition, the shift to green hydrogen is essential. Without it, the environmental benefits are limited.

The Cost Challenge

Green hydrogen is still more expensive than grey or blue hydrogen. As of 2023, green hydrogen costs between $3 and $8 per kilogram, compared to $1–$2 for grey hydrogen. The main drivers of cost are:

– High electricity prices for electrolysis

– Expensive electrolyzers (the machines that split water)

– Limited scale of production

However, experts predict that green hydrogen could drop to $1–$2 per kg by 2030, thanks to falling renewable energy costs and technological advances. Government incentives, like the U.S. Inflation Reduction Act and the European Green Deal, are accelerating this transition.

Storage and Transportation

Hydrogen is the lightest element and highly flammable, which makes storing and transporting it challenging. It must be compressed to high pressures (700 bar for vehicles) or cooled to liquid form (-253°C), both of which require energy and specialized equipment.

Pipelines can transport hydrogen over long distances, but most existing gas pipelines aren’t suitable without modifications. New infrastructure is being developed, such as the HyDeal project in Europe, which aims to create a solar-powered hydrogen supply chain across Spain, France, and Germany.

For vehicles, hydrogen is stored in carbon-fiber tanks that are designed to withstand crashes and leaks. These tanks are rigorously tested and considered safe, but public perception remains a hurdle.

Advantages of Hydrogen Vehicles

Hydrogen vehicles offer several compelling benefits that make them a strong contender in the clean transportation landscape.

Zero Tailpipe Emissions

The most obvious advantage is environmental. Hydrogen vehicles emit only water vapor and warm air. No CO₂, no nitrogen oxides (NOx), no particulate matter. This makes them ideal for improving air quality in cities, where vehicle emissions contribute to smog and respiratory diseases.

In urban areas with high traffic density, replacing diesel buses and trucks with hydrogen models could have an immediate health benefit. For example, a single hydrogen bus can eliminate the equivalent of 50 gasoline cars in terms of emissions.

Fast Refueling

One of the biggest drawbacks of battery-electric vehicles is charging time. Even with fast chargers, it can take 30 minutes to an hour to recharge a car. For commercial fleets or long-distance travel, this downtime is a major limitation.

Hydrogen vehicles, on the other hand, can be refueled in 3–5 minutes—just like a gasoline car. This makes them practical for taxi fleets, delivery services, and road trips. Imagine pulling into a station, filling up in minutes, and driving 400 miles without stopping. That’s the promise of hydrogen.

Long Driving Range

Most hydrogen vehicles offer a range of 300–400 miles on a single tank. The Toyota Mirai, for instance, has an EPA-estimated range of 402 miles. This is significantly more than many battery-electric cars, especially in cold weather, where battery performance drops.

For drivers who frequently travel long distances or live in areas with sparse charging infrastructure, hydrogen offers a reliable alternative.

Energy Density

Hydrogen has a very high energy density by weight—about three times that of gasoline. This makes it ideal for heavy-duty applications where weight is a concern, such as aviation, shipping, and freight transport. Batteries, by contrast, are heavy and take up space, limiting their use in these sectors.

Grid Support and Energy Storage

Hydrogen isn’t just for vehicles. It can also store excess renewable energy. When solar or wind farms generate more power than the grid needs, that energy can be used to produce hydrogen via electrolysis. The hydrogen can then be stored and used later—either to generate electricity in fuel cells or to power vehicles.

This “power-to-gas” approach helps balance the grid and reduces reliance on fossil fuel backups. In Germany, pilot projects are using hydrogen to store wind energy during off-peak hours.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their promise, hydrogen vehicles face significant hurdles that must be overcome for widespread adoption.

Limited Refueling Infrastructure

The biggest barrier today is the lack of hydrogen refueling stations. As of 2023, there are fewer than 1,000 hydrogen stations worldwide, with most concentrated in California, Japan, Germany, and South Korea. In the U.S., over 90% of stations are in California.

Building a nationwide network requires massive investment. Each station costs $1–$2 million to build, and there’s little incentive for private companies to invest without demand. This creates a “chicken-and-egg” problem: no stations mean no cars, and no cars mean no stations.

High Production and Vehicle Costs

Hydrogen vehicles are expensive. The Toyota Mirai starts at around $50,000, and commercial hydrogen trucks can cost over $300,000—far more than their diesel counterparts. Fuel cells rely on rare materials like platinum, which drives up costs.

Similarly, green hydrogen production is still costly. While prices are falling, it’s not yet competitive with fossil fuels without subsidies.

Energy Efficiency Concerns

Hydrogen is less efficient than battery-electric vehicles when you consider the full energy chain. Here’s why:

– Producing hydrogen via electrolysis is about 70–80% efficient.

– Compressing and transporting hydrogen loses another 10–15%.

– Converting hydrogen back to electricity in a fuel cell is 50–60% efficient.

Overall, only about 30–35% of the original renewable energy makes it to the wheels. In contrast, battery-electric vehicles are 77–80% efficient from grid to wheel.

This means hydrogen requires more renewable energy to deliver the same amount of useful power. For passenger cars, this inefficiency is a drawback. But for heavy transport, the benefits of fast refueling and range may outweigh the losses.

Safety and Public Perception

Hydrogen is flammable and requires careful handling. While modern hydrogen tanks are designed to be safe—tested for crashes, fires, and leaks—public fears persist, often fueled by misinformation (like the Hindenburg disaster, which involved a different gas).

Education and transparent safety standards are key to building public trust. In reality, hydrogen is no more dangerous than gasoline when handled properly.

Global Efforts and Future Outlook

Governments and industries around the world are investing in hydrogen as part of their climate strategies.

Government Initiatives

– European Union: The EU’s Hydrogen Strategy aims to install 40 GW of electrolyzers by 2030 and deploy hydrogen in transport, industry, and energy storage.

– United States: The Inflation Reduction Act offers tax credits of up to $3 per kg for green hydrogen, making it more competitive.

– Japan and South Korea: Both countries have national hydrogen roadmaps. Japan plans to have 800,000 hydrogen vehicles by 2030, while South Korea aims for 2.9 million by 2040.

– China: The world’s largest auto market is investing heavily in hydrogen, especially for trucks and buses.

Industry Collaboration

Automakers are partnering to scale up production. The Hydrogen Council, a global coalition of over 100 companies, is driving investment and innovation. Toyota, Hyundai, and BMW are leading in FCEV development, while Shell, BP, and TotalEnergies are building hydrogen refueling networks.

Startups are also playing a role. Companies like Plug Power and Bloom Energy are advancing electrolyzer and fuel cell technology, while Nikola and Hyzon Motors focus on hydrogen trucks.

The Road Ahead

Hydrogen vehicles won’t replace battery-electric cars for everyday use. But they will likely complement them, especially in sectors where batteries fall short. By 2030, we could see hydrogen-powered trucks on highways, hydrogen buses in cities, and even hydrogen ferries crossing oceans.

The key to success will be scaling up green hydrogen production, reducing costs, and building infrastructure. With the right policies and investments, hydrogen can become a cornerstone of the clean energy transition.

Conclusion

Hydrogen vehicles are more than just a futuristic concept—they’re a practical part of the solution to climate change. With zero emissions, fast refueling, and long range, they offer unique advantages that battery-electric vehicles can’t match, especially in heavy transport and industrial applications.

But their success depends on overcoming real challenges: high costs, limited infrastructure, and the need for green hydrogen. This requires coordinated action from governments, industries, and consumers.

As the world races to meet net-zero goals, hydrogen vehicles will play a vital role in decarbonizing the hardest-to-electrify sectors. They won’t replace all cars, but they will help build a cleaner, more resilient energy system. The journey is just beginning, but the destination—a sustainable, hydrogen-powered future—is within reach.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are hydrogen vehicles safe?

Yes, hydrogen vehicles are designed with multiple safety features, including reinforced tanks and leak detection systems. They undergo rigorous testing and are considered as safe as conventional vehicles when properly maintained.

How long does it take to refuel a hydrogen car?

Refueling a hydrogen vehicle takes about 3 to 5 minutes, similar to filling up a gasoline car. This is much faster than charging a battery-electric vehicle.

Can hydrogen vehicles work in cold weather?

Yes, hydrogen vehicles perform well in cold climates. Unlike batteries, fuel cells are not significantly affected by low temperatures, making them reliable in winter conditions.

Where can I refuel a hydrogen car?

Hydrogen refueling stations are currently limited, with most located in California, Japan, Germany, and South Korea. Expansion is ongoing, but infrastructure remains a challenge in many regions.

Is hydrogen better than batteries for electric vehicles?

It depends on the use case. Batteries are more efficient for passenger cars and short trips. Hydrogen excels in long-range, heavy-duty applications where fast refueling and high energy density are critical.

How is green hydrogen produced?

Green hydrogen is made by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electrolysis, powered entirely by renewable energy sources like wind or solar. This method produces no carbon emissions.