Hydrogen refueling stations and natural gas stations represent two distinct paths toward cleaner transportation. While both aim to reduce fossil fuel dependence, they differ significantly in technology, infrastructure needs, environmental benefits, and real-world applications. This article breaks down the pros, cons, and future outlook of each.

Key Takeaways

- Hydrogen stations support zero-emission fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) that emit only water vapor. They are ideal for heavy-duty transport and long-range applications but require costly infrastructure and energy-intensive hydrogen production.

- Natural gas stations power compressed natural gas (CNG) and liquefied natural gas (LNG) vehicles. They offer lower emissions than gasoline and are more widely available, especially for fleet and public transit use.

- Hydrogen production is still largely dependent on fossil fuels. Over 95% of hydrogen today comes from natural gas via steam methane reforming, limiting its green potential unless paired with carbon capture or renewable energy.

- Refueling time is comparable between hydrogen and natural gas. Both can refuel in under 10 minutes, making them practical for commercial and long-haul vehicles.

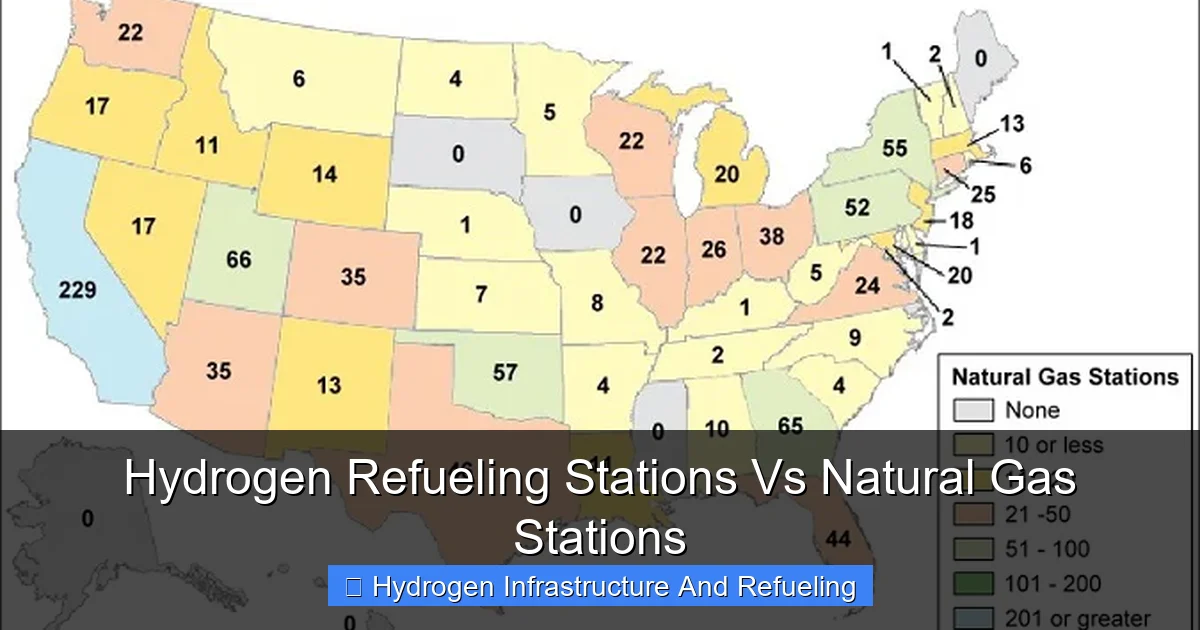

- Infrastructure development lags for both, but natural gas has a head start. There are thousands of natural gas stations in the U.S. versus fewer than 100 hydrogen stations, mostly in California.

- Cost remains a major barrier for hydrogen. Building a hydrogen station can cost $1–3 million, compared to $500,000–$1 million for a natural gas station.

- The future may include hybrid or dual-fuel solutions. Some companies are exploring stations that offer both hydrogen and CNG to serve diverse vehicle types and ease the transition.

📑 Table of Contents

- Hydrogen Refueling Stations Vs Natural Gas Stations: A Comprehensive Comparison

- How Hydrogen Refueling Stations Work

- How Natural Gas Stations Work

- Environmental Impact: Emissions and Sustainability

- Infrastructure and Accessibility

- Cost Analysis: Upfront and Operational Expenses

- Future Outlook: Which Path Will Dominate?

- Conclusion

Hydrogen Refueling Stations Vs Natural Gas Stations: A Comprehensive Comparison

As the world races to cut carbon emissions and combat climate change, the transportation sector is undergoing a major transformation. Electric vehicles (EVs) have dominated headlines, but two alternative fueling technologies—hydrogen refueling stations and natural gas stations—are quietly gaining traction, especially for heavy-duty and long-range applications. While both offer cleaner alternatives to gasoline and diesel, they differ dramatically in how they work, how they’re built, and how they impact the environment.

Hydrogen refueling stations support fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), which generate electricity on board using hydrogen and oxygen, emitting only water vapor. Natural gas stations, on the other hand, fuel vehicles that burn compressed natural gas (CNG) or liquefied natural gas (LNG), reducing tailpipe emissions compared to conventional fuels but still releasing carbon dioxide. The choice between these two isn’t just technical—it’s strategic, economic, and environmental.

This article dives deep into the world of hydrogen refueling stations versus natural gas stations. We’ll explore how each works, their infrastructure requirements, environmental impacts, costs, real-world use cases, and what the future might hold. Whether you’re a fleet manager, policymaker, or simply curious about the future of clean transportation, this guide will help you understand which path—or combination—might lead us toward a more sustainable future.

How Hydrogen Refueling Stations Work

Visual guide about Hydrogen Refueling Stations Vs Natural Gas Stations

Image source: energy.gov

Hydrogen refueling stations are the backbone of the fuel cell electric vehicle (FCEV) ecosystem. Unlike battery electric vehicles that store energy in large batteries, FCEVs generate electricity through a chemical reaction inside a fuel cell stack. This reaction combines hydrogen (H₂) from the tank with oxygen (O₂) from the air, producing electricity, heat, and water as the only byproduct.

The Refueling Process

Refueling a hydrogen vehicle is surprisingly similar to filling up a gasoline car. The driver pulls up to a dispenser, connects a nozzle to the vehicle’s fuel inlet, and initiates the transfer. High-pressure hydrogen—typically stored at 350 or 700 bar—flows from the station into the vehicle’s onboard tanks. The entire process takes 3 to 5 minutes for passenger cars and up to 10 minutes for larger vehicles like buses or trucks.

One key difference? Safety. Hydrogen is the lightest and most flammable element, so stations are equipped with advanced leak detection, ventilation systems, and emergency shut-offs. Despite these concerns, hydrogen has a strong safety record when handled properly, thanks to strict codes and standards like those from the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA).

Hydrogen Production and Delivery

Here’s where things get complicated. Hydrogen doesn’t exist in pure form in nature—it must be extracted from other compounds. Today, over 95% of hydrogen is produced via steam methane reforming (SMR), a process that uses natural gas as a feedstock. This “gray hydrogen” still emits CO₂, undermining its environmental benefits.

However, “green hydrogen”—produced using renewable electricity to split water via electrolysis—is growing in popularity. While still a small fraction of total production, green hydrogen offers a truly zero-emission pathway, especially when powered by wind, solar, or hydroelectric energy.

Hydrogen can be delivered to stations via pipelines (rare), tube trailers (common), or produced on-site using electrolyzers. On-site production reduces transportation costs and emissions but requires significant space and energy.

Real-World Examples

California leads the U.S. in hydrogen infrastructure, with over 60 operational stations—mostly in the Bay Area and Los Angeles. Companies like Toyota, Hyundai, and Honda offer FCEVs like the Mirai and NEXO, which are primarily leased or sold in these regions. In Europe, Germany’s H2 Mobility initiative aims to build a nationwide network of 100 stations by 2025. Japan and South Korea are also investing heavily in hydrogen, with plans to support everything from cars to buses and even ships.

How Natural Gas Stations Work

Natural gas stations are more familiar and widely available than hydrogen stations. They support vehicles that run on compressed natural gas (CNG) or liquefied natural gas (LNG), both of which are primarily composed of methane (CH₄). While not zero-emission, natural gas burns cleaner than gasoline or diesel, producing up to 25% fewer greenhouse gases and significantly lower levels of nitrogen oxides (NOx) and particulate matter.

The Refueling Process

Refueling a CNG or LNG vehicle is also quick and straightforward. CNG is stored at high pressure (3,000–3,600 psi) in onboard tanks, while LNG is kept at cryogenic temperatures (-260°F) in insulated tanks. Both can be dispensed in under 10 minutes, making them ideal for fleet vehicles like buses, delivery trucks, and taxis.

CNG is more common for light- and medium-duty vehicles due to its lower energy density. LNG, with its higher energy content, is preferred for long-haul trucks and marine applications. Many stations offer both options, allowing fleets to choose based on range and vehicle type.

Natural Gas Production and Delivery

Natural gas is extracted from underground reservoirs through drilling and hydraulic fracturing (fracking). It’s then processed to remove impurities and delivered via pipelines to distribution centers and refueling stations. Some stations compress or liquefy gas on-site, while others receive pre-processed fuel via tanker trucks.

One advantage of natural gas infrastructure is its existing backbone. The U.S. has over 180,000 miles of natural gas pipelines, making it easier and cheaper to expand refueling networks compared to building entirely new hydrogen systems.

Real-World Examples

Natural gas vehicles (NGVs) are already in widespread use. In the U.S., over 170,000 NGVs are on the road, including city buses, garbage trucks, and delivery vans. Companies like UPS and Waste Management have large CNG fleets, citing lower fuel costs and reduced emissions. In countries like Iran, China, and Argentina, NGVs make up a significant portion of the vehicle fleet due to government incentives and abundant natural gas reserves.

Environmental Impact: Emissions and Sustainability

When it comes to environmental performance, hydrogen and natural gas stations offer different trade-offs. The key question isn’t just about tailpipe emissions—it’s about the full lifecycle, from production to delivery to use.

Hydrogen: The Promise of Zero Emissions

FCEVs emit only water vapor during operation, making them truly zero-emission at the tailpipe. But the environmental benefit depends heavily on how the hydrogen is made. Gray hydrogen, produced from natural gas, can result in higher lifecycle emissions than diesel in some cases due to methane leaks and CO₂ release.

Blue hydrogen, which uses carbon capture and storage (CCS) to trap emissions from SMR, reduces CO₂ output by up to 90%. Green hydrogen, powered by renewables, is the gold standard—offering near-zero emissions across the board.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), green hydrogen could supply up to 24% of global energy needs by 2050, but it currently accounts for less than 1% of production. Scaling it up will require massive investments in renewable energy and electrolyzer technology.

Natural Gas: Cleaner, But Not Clean

Natural gas vehicles emit fewer pollutants than gasoline or diesel, but they’re not emissions-free. CNG produces about 25% less CO₂ than gasoline, while LNG offers similar reductions. However, methane—the main component of natural gas—is a potent greenhouse gas, with over 80 times the warming power of CO₂ over a 20-year period. Leaks during extraction, transportation, and refueling can significantly offset the climate benefits.

That said, natural gas can play a transitional role. It’s a “bridge fuel” that reduces emissions today while zero-emission technologies mature. For fleets that need long range and quick refueling, NGVs offer a practical step toward sustainability.

Lifecycle Comparison

A 2022 study by the Union of Concerned Scientists found that FCEVs powered by green hydrogen have the lowest lifecycle emissions—lower than battery EVs in some regions. However, FCEVs using gray hydrogen can be worse than gasoline vehicles. NGVs, while cleaner than diesel, still fall short of true zero-emission goals.

The takeaway? Both technologies can be part of a cleaner future, but only if paired with sustainable production methods and strict emissions controls.

Infrastructure and Accessibility

Infrastructure is one of the biggest hurdles for both hydrogen and natural gas stations. Building a refueling network requires massive investment, regulatory support, and public acceptance.

Hydrogen Infrastructure Challenges

Hydrogen stations are expensive and complex. The average cost ranges from $1 million to $3 million per station, depending on size and technology. That’s 2–6 times more than a typical natural gas station. High costs stem from specialized materials (hydrogen embrittles steel), safety systems, and low demand.

As of 2024, the U.S. has fewer than 100 hydrogen stations, with over 90% in California. Europe and Asia have more, but the global network remains sparse. This “chicken-and-egg” problem—few stations mean few vehicles, and few vehicles mean little incentive to build stations—slows adoption.

Natural Gas Infrastructure Advantages

Natural gas stations are far more common. The U.S. has over 1,800 public and private CNG stations, with many more planned. Costs are lower—typically $500,000 to $1 million—and the existing pipeline network reduces delivery challenges.

Many natural gas stations are co-located with gasoline stations or fleet depots, making them convenient for commercial users. Some even offer time-fill systems, where vehicles refuel slowly overnight, reducing peak demand and costs.

Future Expansion and Integration

The future may see hybrid stations that offer both hydrogen and natural gas. Pilot projects in California and Germany are testing multi-fuel stations to serve diverse vehicle types. Additionally, renewable natural gas (RNG)—produced from organic waste—can further reduce emissions and improve sustainability.

Governments are stepping in with incentives. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits for hydrogen production and station development. The European Union’s REPowerEU plan aims to boost green hydrogen capacity to 10 million tons by 2030.

Cost Analysis: Upfront and Operational Expenses

Cost is a critical factor in the adoption of any fueling technology. Let’s break down the expenses for hydrogen and natural gas stations.

Capital Costs

– Hydrogen Station: $1–3 million per station. Includes compressors, storage tanks, dispensers, safety systems, and land. On-site electrolysis adds $500,000–$1 million.

– Natural Gas Station: $500,000–$1 million. Lower due to simpler technology and existing infrastructure.

Operational Costs

– Hydrogen: High energy use for compression and cooling. Green hydrogen production can cost $3–$6 per kilogram, though prices are falling. Maintenance is complex and specialized.

– Natural Gas: Lower energy costs. CNG prices average $2–$3 per gasoline gallon equivalent (GGE), often cheaper than diesel. Maintenance is routine and widely available.

Vehicle Costs

FCEVs like the Toyota Mirai start around $50,000—much higher than comparable EVs or NGVs. CNG vehicles, such as the Ford F-150, cost $5,000–$10,000 more than gasoline versions but offer fuel savings over time.

For fleets, the total cost of ownership (TCO) often favors natural gas due to lower fuel and maintenance costs. However, as hydrogen production scales and technology improves, FCEVs could become more competitive.

Future Outlook: Which Path Will Dominate?

The race between hydrogen and natural gas stations isn’t a zero-sum game. Both have roles to play in the transition to sustainable transportation.

Hydrogen’s Niche

Hydrogen excels in applications where batteries fall short: long-haul trucking, aviation, shipping, and heavy industry. Its high energy density and fast refueling make it ideal for vehicles that need to travel far and return quickly. Companies like Nikola and Hyundai are developing hydrogen-powered trucks, while Airbus plans hydrogen-powered aircraft by 2035.

Natural Gas as a Bridge

Natural gas will likely remain a transitional fuel, especially for fleets and regions with abundant gas reserves. RNG can further reduce emissions, and dual-fuel systems may allow vehicles to switch between CNG and hydrogen as infrastructure evolves.

Policy and Innovation

Government support will be crucial. Incentives for green hydrogen, carbon pricing, and fleet mandates can accelerate adoption. Meanwhile, advances in electrolysis, fuel cells, and storage will drive down costs and improve efficiency.

The future may not be hydrogen or natural gas—but both, working together to decarbonize transport.

Conclusion

Hydrogen refueling stations and natural gas stations represent two different visions for cleaner transportation. Hydrogen offers the promise of zero emissions and high energy density, but faces steep costs and infrastructure challenges. Natural gas provides a practical, lower-cost alternative with immediate emissions reductions, though it’s not a long-term solution.

The choice between them depends on use case, geography, and policy. For now, natural gas has the edge in availability and affordability, while hydrogen leads in innovation and potential. As technology advances and sustainability goals tighten, we may see a hybrid future where both fuels coexist, each serving the roles they do best.

The road to decarbonization won’t be paved by a single fuel. It will be built on diversity, innovation, and a commitment to progress—one refueling station at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are hydrogen refueling stations safe?

Yes, hydrogen refueling stations are designed with multiple safety features, including leak detection, ventilation, and automatic shut-offs. Hydrogen disperses quickly into the air, reducing fire risk, and strict safety standards ensure reliable operation.

How long does it take to refuel a hydrogen vehicle?

Refueling a hydrogen vehicle takes 3 to 5 minutes for passenger cars and up to 10 minutes for larger vehicles like buses or trucks—similar to gasoline refueling and much faster than most EV charging.

Can natural gas vehicles use renewable natural gas (RNG)?

Yes, many CNG and LNG vehicles can run on renewable natural gas, which is produced from organic waste like landfills, farms, and wastewater. RNG can reduce lifecycle emissions by up to 80% compared to fossil fuels.

Why are there so few hydrogen stations?

Hydrogen stations are expensive to build and require specialized technology. Low vehicle demand and limited production capacity have slowed expansion, though government incentives and growing interest in FCEVs are helping.

Is hydrogen more expensive than natural gas?

Yes, hydrogen is currently more expensive to produce and dispense. Green hydrogen costs $3–$6 per kilogram, while CNG costs $2–$3 per gasoline gallon equivalent. However, prices are expected to fall as technology improves.

Can a station offer both hydrogen and natural gas?

Yes, some pilot stations are testing dual-fuel capabilities to serve both FCEVs and NGVs. This approach can maximize infrastructure use and support a smoother transition to cleaner fuels.