Hydrogen refueling stations face major hurdles including high costs, complex storage, safety risks, and limited infrastructure. Despite the promise of clean energy, building a reliable hydrogen network remains a significant challenge.

Key Takeaways

- High Capital and Operational Costs: Building and maintaining hydrogen refueling stations is expensive due to specialized equipment, energy-intensive production, and low demand.

- Hydrogen Storage and Transportation Difficulties: Hydrogen’s low density and high flammability require advanced storage solutions like high-pressure tanks or cryogenic systems, making transport complex and costly.

- Safety Concerns and Public Perception: Despite strong safety protocols, hydrogen’s flammability and past incidents like the Hindenburg create public fear, requiring rigorous standards and education.

- Limited Infrastructure and Scalability Issues: The sparse network of stations hinders adoption, and scaling up requires massive investment and coordination across industries.

- Energy Inefficiency in Production: Most hydrogen is produced from fossil fuels, and even green hydrogen via electrolysis loses significant energy, reducing overall efficiency.

- Regulatory and Standardization Gaps: Inconsistent regulations and lack of global standards slow deployment and increase compliance costs for operators.

- Competition with Battery Electric Vehicles: The rapid growth of EVs challenges hydrogen’s role in transportation, especially for passenger cars.

📑 Table of Contents

- What Are the Challenges of Hydrogen Refueling Stations?

- High Capital and Operational Costs

- Hydrogen Storage and Transportation Difficulties

- Safety Concerns and Public Perception

- Limited Infrastructure and Scalability Issues

- Energy Inefficiency in Production

- Regulatory and Standardization Gaps

- Competition with Battery Electric Vehicles

- Conclusion

What Are the Challenges of Hydrogen Refueling Stations?

Imagine pulling up to a fueling station, but instead of gasoline or electricity, you’re filling your car with hydrogen—clean, quiet, and emission-free. Sounds futuristic, right? That future is already here in a few places, but it’s not without serious roadblocks. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) promise a greener alternative to traditional combustion engines and even battery electric vehicles (EVs), especially for long-haul trucks, buses, and industrial equipment. But for hydrogen to go mainstream, we need a reliable network of refueling stations. And that’s where the real challenges begin.

Hydrogen refueling stations are the backbone of the hydrogen economy. Without them, even the most advanced fuel cell vehicles can’t operate. Yet, despite growing interest and investment, these stations remain rare, expensive, and technically complex. From production to delivery, storage to safety, every step in the hydrogen supply chain presents unique obstacles. This article dives deep into the major challenges facing hydrogen refueling stations today—exploring why they’re so hard to build, maintain, and scale.

Whether you’re a policymaker, engineer, investor, or just curious about clean energy, understanding these challenges is key to seeing where hydrogen fits in our sustainable future. Let’s break down the hurdles—and see what’s being done to overcome them.

High Capital and Operational Costs

One of the biggest barriers to hydrogen refueling stations is cost—both upfront and ongoing. Building a single hydrogen station can cost anywhere from $1 million to $3 million, depending on size, location, and technology. That’s significantly more than a typical gasoline station or even a fast-charging EV station. For comparison, a high-speed EV charger might cost $50,000 to $150,000, while a hydrogen station requires far more specialized equipment.

Why Are Hydrogen Stations So Expensive?

The high price tag comes from several factors. First, hydrogen must be produced, stored, and dispensed under extreme conditions. Most stations use high-pressure compressors to store hydrogen at 350 or 700 bar (5,000 to 10,000 psi)—pressures far greater than those in natural gas systems. These compressors are complex, energy-intensive, and expensive to install and maintain.

Second, hydrogen is highly reactive and can embrittle metals, meaning all components—from pipes to valves to storage tanks—must be made from specialized, corrosion-resistant materials like stainless steel or advanced composites. These materials aren’t cheap, and they’re not always readily available in large quantities.

Third, many hydrogen stations are still in the pilot or demonstration phase, meaning they benefit from little to no economies of scale. Suppliers charge premium prices because demand is low and production volumes are small. As long as only a few stations are built, manufacturers can’t reduce costs through mass production.

Operational Expenses Add Up

It’s not just the initial build that’s costly—running a hydrogen station is expensive too. Electricity is a major expense, especially if the station produces hydrogen on-site via electrolysis. Electrolysis splits water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity, and if that power comes from the grid (rather than renewable sources), it can be pricey and carbon-intensive.

Then there’s maintenance. Hydrogen systems require frequent inspections and servicing due to the high pressures and potential for leaks. Technicians need special training to handle hydrogen safely, and qualified personnel are still relatively rare. Downtime for repairs can be longer and more disruptive than at conventional stations.

Fuel delivery is another cost driver. If hydrogen isn’t produced on-site, it must be transported from a central production facility—usually by truck in compressed or liquid form. This adds transportation costs, fuel for delivery vehicles, and the risk of supply delays. In remote areas, these logistics become even more challenging.

Low Utilization Rates Worsen the Problem

Even if a station is built, it may not get much use. As of 2023, there are fewer than 200 hydrogen refueling stations in the United States, and most serve only a handful of vehicles per day. This low utilization means the station can’t spread its high fixed costs over many customers, making it harder to turn a profit.

For example, the California Fuel Cell Partnership reports that many stations in the state operate at less than 20% capacity. Without more fuel cell vehicles on the road, stations struggle to justify their existence—let alone expand. It’s a classic chicken-and-egg problem: people won’t buy FCEVs without stations, but companies won’t build stations without customers.

Hydrogen Storage and Transportation Difficulties

Hydrogen might be the lightest element in the universe, but storing and moving it is anything but simple. Its physical properties make it one of the most challenging fuels to handle at scale.

The Problem with Hydrogen’s Low Density

Hydrogen has an incredibly low energy density by volume. At ambient temperature and pressure, a cubic meter of hydrogen contains far less energy than the same volume of gasoline or even natural gas. To make it practical for vehicles, hydrogen must be compressed or liquefied.

Most hydrogen refueling stations store fuel in high-pressure gaseous form—typically at 350 or 700 bar. This requires massive, reinforced tanks and powerful compressors. Compressing hydrogen to these pressures consumes a lot of energy—up to 10–15% of the fuel’s total energy content. That’s a significant efficiency loss before the fuel even reaches the vehicle.

Alternatively, hydrogen can be cooled to -253°C (-423°F) to become a liquid. Liquid hydrogen (LH2) takes up much less space, making it easier to transport. But liquefaction is even more energy-intensive, using about 30% of the hydrogen’s energy. Plus, LH2 tanks must be heavily insulated to prevent boil-off—hydrogen slowly evaporates even in the best containers.

Transportation Challenges

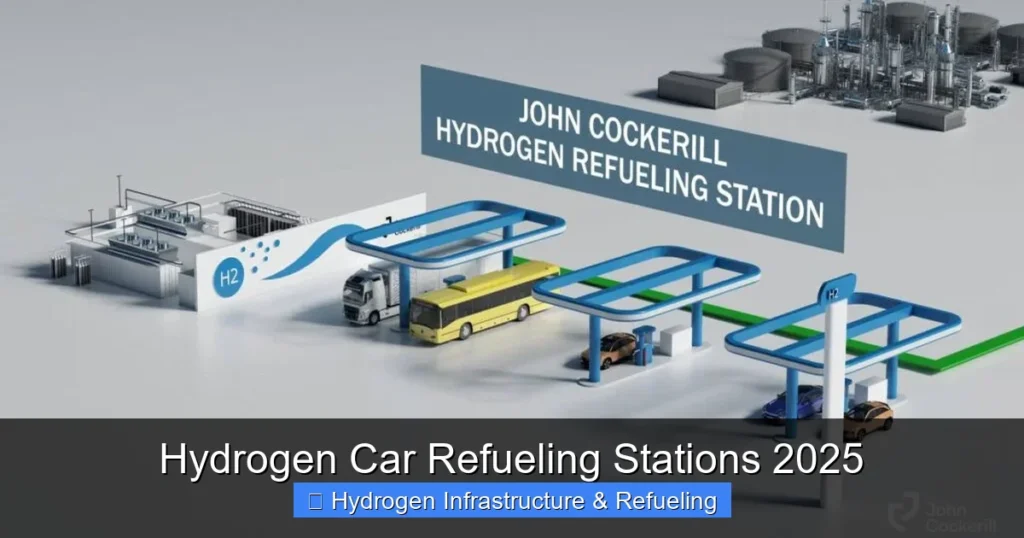

Getting hydrogen from production sites to refueling stations is a logistical headache. There are three main methods: tube trailers (for compressed gas), cryogenic tankers (for liquid hydrogen), and pipelines.

Tube trailers are the most common for short distances. They carry multiple high-pressure cylinders on a truck, but each trailer holds only a few hundred kilograms of hydrogen—enough for maybe 50–100 vehicle fills. That’s not much, especially compared to a gasoline tanker that can deliver thousands of gallons.

Cryogenic tankers can carry more hydrogen by volume, but they’re expensive, complex, and require careful handling to avoid leaks or pressure buildup. Plus, liquid hydrogen must be kept extremely cold, which limits how long it can be stored during transport.

Pipelines are the most efficient way to move large volumes of hydrogen over long distances—similar to natural gas pipelines. But building a hydrogen pipeline network is a massive infrastructure project. Hydrogen can damage existing natural gas pipelines through embrittlement, so new pipelines must be specially designed or retrofitted. Only a few hydrogen pipelines exist today, mostly in industrial areas like the Gulf Coast.

On-Site Production vs. Delivery

Some stations produce hydrogen on-site using electrolysis, powered by solar or wind energy. This avoids transportation costs and reduces emissions—if the electricity is clean. But on-site production requires space, equipment, and a reliable power supply. It also means the station must manage both hydrogen production and dispensing, increasing complexity.

Other stations rely on delivered hydrogen, which introduces supply chain risks. If a delivery truck is delayed or a production plant goes offline, the station may run out of fuel. This unpredictability makes it hard to guarantee service, especially in rural or underserved areas.

Safety Concerns and Public Perception

Hydrogen is highly flammable—it ignites easily and burns with a nearly invisible flame. These properties raise legitimate safety concerns, both for station operators and the public.

Understanding Hydrogen’s Risks

Hydrogen has a wide flammability range (4% to 75% in air), meaning it can ignite even at low concentrations. It also has a low ignition energy—just a small spark can set it off. And because it’s so light, it disperses quickly into the air, which can be both a blessing and a curse. On one hand, it reduces the risk of pooling and explosion. On the other, it can spread unnoticed, increasing the chance of ignition in enclosed spaces.

Despite these risks, hydrogen is not inherently more dangerous than other fuels. Gasoline, natural gas, and even lithium-ion batteries all pose fire and explosion hazards. The key is proper design, monitoring, and maintenance.

Modern hydrogen stations include multiple safety systems: leak detectors, automatic shut-off valves, ventilation systems, and fire suppression equipment. Sensors continuously monitor for hydrogen leaks, and if a problem is detected, the system can isolate the fuel source and alert operators.

Public Fear and Misinformation

Even with strong safety records, public perception remains a hurdle. Many people associate hydrogen with the Hindenburg disaster of 1937, when a German airship filled with hydrogen caught fire and crashed. While the Hindenburg’s design flaws and use of flammable materials contributed to the tragedy, modern hydrogen systems are far safer.

Still, the image of a fiery explosion sticks in people’s minds. Overcoming this stigma requires education and transparency. Station operators must communicate how safety systems work, share incident data, and engage with communities before building new stations.

In some cases, local opposition has delayed or blocked hydrogen projects. Residents worry about leaks, explosions, or property devaluation. Addressing these concerns early—through public meetings, safety demonstrations, and third-party audits—can help build trust.

Regulatory and Certification Challenges

Safety regulations for hydrogen are still evolving. Different countries and even states have varying standards for station design, operation, and inspection. This inconsistency makes it harder for companies to deploy stations at scale.

For example, the U.S. follows guidelines from the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA 2), but local fire marshals may interpret them differently. In Europe, the ISO/TS 19887 standard provides guidance, but implementation varies by country.

Certification processes can be slow and costly. Equipment must be tested and approved by multiple agencies, and changes to station design may require re-certification. These delays add time and expense to every project.

Limited Infrastructure and Scalability Issues

Even in countries leading the hydrogen push—like Japan, South Korea, and Germany—the number of refueling stations is still small. The U.S. has fewer than 100 public hydrogen stations, mostly in California. China is building rapidly but still has only a few hundred. This sparse network makes long-distance travel nearly impossible for FCEV owners.

The Chicken-and-Egg Problem

The lack of stations discourages consumers from buying hydrogen vehicles. Why invest in a car you can’t refuel outside your city? Automakers, in turn, are hesitant to produce more FCEVs without a reliable fueling network. This creates a cycle of low demand and low investment.

Some regions are trying to break this cycle with government support. California, for instance, has funded over 100 hydrogen stations through its Clean Transportation Program. But even there, growth has been slow. Stations open, then close due to low use or technical issues. Others operate intermittently, frustrating drivers.

Geographic and Urban Challenges

Building stations in cities is especially tough. Urban areas have high land costs, strict zoning laws, and limited space. A hydrogen station needs room for storage tanks, compressors, dispensers, and safety setbacks—often requiring a larger footprint than a gas station.

In rural areas, the problem is the opposite: low population density means fewer potential customers. A station might serve only a few vehicles per week, making it hard to justify the investment.

Scalability Requires Coordination

Scaling up hydrogen infrastructure isn’t just about building more stations. It requires coordination across industries: energy producers, automakers, fuel distributors, regulators, and utilities. Each plays a role in the supply chain, and delays in one area can stall the entire system.

For example, if electrolyzer manufacturers can’t keep up with demand, stations that rely on on-site production will face delays. If automakers don’t increase FCEV production, stations won’t get enough customers. And if utilities don’t provide affordable renewable power, green hydrogen won’t be cost-competitive.

Energy Inefficiency in Production

Hydrogen is often called a “clean fuel” because fuel cell vehicles emit only water. But that’s only half the story. The environmental impact depends heavily on how the hydrogen is made.

Grey, Blue, and Green Hydrogen

Most hydrogen today is “grey”—produced from natural gas through steam methane reforming (SMR). This process emits large amounts of CO₂, making it far from clean. In fact, producing one kilogram of grey hydrogen can release 9–12 kg of CO₂.

“Blue” hydrogen uses the same process but captures and stores the CO₂ emissions. It’s cleaner than grey hydrogen but still relies on fossil fuels and requires carbon capture infrastructure, which is expensive and not yet widely deployed.

“Green” hydrogen is produced via electrolysis using renewable electricity. It’s truly emissions-free—if the power comes from wind, solar, or hydro. But green hydrogen is currently expensive, accounting for less than 1% of global production.

The Efficiency Problem

Even green hydrogen isn’t perfectly efficient. Electrolysis converts about 70–80% of electrical energy into hydrogen. Then, compressing or liquefying the hydrogen loses another 10–30%. Finally, converting hydrogen back to electricity in a fuel cell is only 50–60% efficient.

So, from electricity to wheel, the total efficiency of a hydrogen FCEV might be 25–35%. In contrast, a battery electric vehicle (BEV) can achieve 70–90% efficiency—electricity goes straight from the grid to the battery to the motor.

This means hydrogen requires far more energy to deliver the same amount of transportation. For every mile driven, a hydrogen car might use two to three times more electricity than an EV.

Opportunity Cost of Energy Use

Using renewable energy to make hydrogen means that energy isn’t available for other uses—like powering homes, businesses, or charging EVs. In a world with limited clean energy, this raises questions about priority. Should we use wind and solar to directly electrify transportation, or convert it to hydrogen for fuel cells?

Experts argue that hydrogen makes the most sense for applications that are hard to electrify—like aviation, shipping, and heavy industry. For passenger cars, batteries are often more efficient and practical.

Regulatory and Standardization Gaps

Clear, consistent rules are essential for building a safe and reliable hydrogen infrastructure. But today, regulations are fragmented and still developing.

Inconsistent Global Standards

Different countries have different rules for hydrogen production, storage, transportation, and dispensing. This makes it hard for companies to design equipment that works worldwide. A compressor built for the U.S. market might not meet European safety standards, and vice versa.

Even within countries, regulations can vary. In the U.S., states like California have aggressive hydrogen goals and supportive policies, while others have little interest or infrastructure. This patchwork approach slows national progress.

Lack of Harmonized Codes

Technical standards—like those for hydrogen purity, dispenser interfaces, or tank certification—are still being refined. The Society of Automotive Engineers (SAE) and International Organization for Standardization (ISO) have published guidelines, but adoption isn’t universal.

For example, hydrogen dispensers must meet strict requirements for flow rate, pressure, and communication with vehicles. But if standards change, existing equipment may need upgrades or replacement—adding cost and complexity.

Permitting and Approval Delays

Getting a hydrogen station approved can take months or even years. Permitting involves multiple agencies: fire departments, environmental regulators, zoning boards, and utility companies. Each has its own requirements, and delays in one can hold up the whole project.

In some cases, local officials lack experience with hydrogen and may impose overly strict conditions or reject applications outright. Education and outreach are essential to streamline the process.

Competition with Battery Electric Vehicles

Perhaps the biggest challenge to hydrogen refueling stations is the rapid rise of battery electric vehicles (BEVs). EVs have surged in popularity, supported by falling battery costs, growing charging networks, and strong government incentives.

Why BEVs Are Winning (For Now)

BEVs are simpler, more efficient, and cheaper to operate than FCEVs. They don’t require complex fuel cells, high-pressure tanks, or hydrogen infrastructure. Charging at home is convenient, and public networks are expanding quickly.

For most drivers—especially in cities—BEVs meet their needs. Daily commutes, errands, and short trips don’t require the range or refueling speed that hydrogen offers. And with fast chargers now delivering 80% charge in 20–30 minutes, the gap is narrowing.

Where Hydrogen Still Has an Edge

Hydrogen isn’t dead—it just has a narrower role. FCEVs can refuel in 3–5 minutes and offer ranges of 300–400 miles, similar to gasoline cars. This makes them attractive for long-haul trucking, buses, and fleet vehicles that can’t afford long charging stops.

Some experts believe hydrogen will complement batteries, not compete with them. Heavy-duty transport, aviation, and industrial processes may be better suited to hydrogen due to energy density and refueling speed.

But for passenger cars, the momentum is with BEVs. Unless hydrogen stations become far more common and affordable, most consumers will choose the simpler, more established option.

Conclusion

Hydrogen refueling stations hold great promise for a clean energy future. They could enable zero-emission transportation, reduce dependence on fossil fuels, and support renewable energy integration. But that future is still far from reality.

The challenges are real and multifaceted: high costs, complex storage, safety concerns, limited infrastructure, energy inefficiency, regulatory gaps, and fierce competition from batteries. Overcoming these hurdles will require innovation, investment, and collaboration across industries and governments.

Progress is being made. Countries like Japan and South Korea are building national hydrogen strategies. Companies like Toyota, Hyundai, and Nikola are advancing fuel cell technology. And new projects are exploring green hydrogen production at scale.

But for hydrogen to succeed, we need more than technology—we need a shift in mindset. Policymakers must create stable, supportive regulations. Investors must fund long-term infrastructure. And the public must learn to trust hydrogen as a safe, viable fuel.

The road ahead is long, but not impossible. With the right approach, hydrogen refueling stations could one day be as common as gas pumps—powering a cleaner, more sustainable world.

Frequently Asked Questions

Why are hydrogen refueling stations so expensive to build?

Hydrogen stations require specialized, high-pressure equipment, corrosion-resistant materials, and advanced safety systems, all of which drive up costs. Additionally, low demand and lack of economies of scale keep prices high.

Is hydrogen safe to use at refueling stations?

Yes, when properly managed. Modern stations include leak detectors, automatic shut-offs, and ventilation systems. Hydrogen disperses quickly, reducing explosion risk, but strict safety protocols are essential.

How is hydrogen transported to refueling stations?

Hydrogen is typically delivered by tube trailers (compressed gas) or cryogenic tankers (liquid hydrogen). Pipelines are efficient but rare and expensive to build.

Can hydrogen stations produce fuel on-site?

Yes, some stations use electrolysis to split water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. This avoids transportation costs but requires space, equipment, and a reliable power source.

Why aren’t there more hydrogen refueling stations?

High costs, low vehicle adoption, and limited infrastructure create a chicken-and-egg problem. Without enough FCEVs, stations can’t justify investment, and without stations, consumers won’t buy FCEVs.

Will hydrogen ever compete with electric vehicles?

For passenger cars, battery EVs are currently more efficient and practical. Hydrogen may find a stronger role in heavy-duty transport, aviation, and industries where batteries are less viable.