Hydrogen cars and electric vehicles (EVs) both aim to reduce emissions, but they differ significantly in environmental impact, energy efficiency, and infrastructure. While hydrogen fuel cell vehicles emit only water, their overall green credentials depend heavily on how the hydrogen is produced. In contrast, EVs are generally more energy-efficient and benefit from cleaner electricity grids over time.

Key Takeaways

- Hydrogen production is energy-intensive: Most hydrogen today comes from natural gas, which releases carbon dioxide, making it less eco-friendly unless green hydrogen (from renewable energy) is used.

- Electric vehicles are more energy-efficient: EVs convert about 77% of electrical energy to power at the wheels, compared to only 25–35% for hydrogen cars due to multiple energy conversion steps.

- Charging infrastructure favors EVs: Electric charging stations are far more widespread and easier to install than hydrogen refueling networks, which are still in early development.

- Hydrogen excels in long-range and heavy-duty transport: For trucks, buses, and long-haul freight, hydrogen may offer faster refueling and better range than current battery technology.

- Lifecycle emissions matter: Both vehicle types must be evaluated from manufacturing to disposal, including battery production and hydrogen storage, to assess true environmental impact.

- Renewable energy is the game-changer: The environmental benefit of both technologies increases dramatically as electricity grids shift to wind, solar, and other clean sources.

- Policy and innovation will shape the future: Government support, technological advances, and consumer adoption will determine whether hydrogen or electric dominates the clean transport landscape.

Quick Answers to Common Questions

Are hydrogen cars really zero-emission?

Only at the tailpipe. While they emit only water vapor when driving, most hydrogen today is produced from natural gas, which releases CO₂. True zero emissions require green hydrogen made with renewable energy.

Can hydrogen cars charge at home?

No. Unlike EVs, hydrogen cars cannot be refueled at home. They require specialized high-pressure refueling stations, which are currently very limited.

Which is cheaper to operate: hydrogen or electric cars?

Electric cars are generally cheaper to operate. Electricity is less expensive than hydrogen per mile, and EVs are more energy-efficient, reducing fuel and maintenance costs.

How long does it take to refuel a hydrogen car?

About 3–5 minutes — similar to gasoline. This is faster than most EV charging, though ultra-fast chargers can get an EV to 80% in 20–30 minutes.

Will hydrogen cars replace electric cars?

Unlikely for passenger vehicles. EVs are more efficient and better supported by infrastructure. Hydrogen may complement EVs in heavy transport and niche applications.

📑 Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Race Toward Cleaner Transportation

- How Hydrogen Cars Work — And Their Environmental Footprint

- Electric Vehicles: Efficiency and the Grid Factor

- Comparing Lifecycle Emissions: EVs vs. Hydrogen Cars

- Where Hydrogen Cars Shine: Niche Applications

- The Role of Policy and Innovation

- Conclusion: Which Is Better for the Environment?

Introduction: The Race Toward Cleaner Transportation

The world is shifting gears. As climate change accelerates and air pollution becomes a growing concern in cities, the automotive industry is under pressure to go green. Two leading contenders have emerged in the race to replace gasoline and diesel vehicles: battery electric vehicles (EVs) and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs). Both promise zero tailpipe emissions, but they take very different paths to get there.

Electric cars, like Teslas and Nissan Leafs, run on rechargeable batteries and electric motors. They’re already common on roads worldwide, supported by expanding charging networks and falling battery costs. Hydrogen cars, such as the Toyota Mirai or Hyundai Nexo, use fuel cells to generate electricity from hydrogen gas, emitting only water vapor. They’re rarer but gaining attention, especially for long-distance and heavy-duty applications.

So, which is truly better for the environment? The answer isn’t black and white. It depends on how the energy is produced, how efficiently it’s used, and what happens over the full lifecycle of the vehicle. This article dives deep into the environmental pros and cons of hydrogen and electric cars, helping you understand which technology might lead us toward a cleaner, greener future.

How Hydrogen Cars Work — And Their Environmental Footprint

Visual guide about Are Hydrogen Cars Better for the Environment Than Electric?

Image source: img.drivemag.net

To judge whether hydrogen cars are better for the environment, we first need to understand how they operate. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles use a chemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen to produce electricity, which powers an electric motor. The only byproduct? Water. That sounds perfect — no CO₂, no smog, just clean water dripping from the tailpipe.

But here’s the catch: the hydrogen itself has to come from somewhere. And right now, most of it doesn’t come from clean sources.

The Problem with “Grey” and “Blue” Hydrogen

About 95% of the world’s hydrogen is currently produced through a process called steam methane reforming (SMR), which uses natural gas as a feedstock. This method releases significant amounts of carbon dioxide — up to 12 kilograms of CO₂ for every kilogram of hydrogen produced. This type is known as “grey hydrogen.”

Some newer methods capture and store the CO₂ emissions, creating “blue hydrogen.” While this reduces the carbon footprint, it’s not zero-emission, and the capture process is energy-intensive and not yet widely deployed.

Only a small fraction of hydrogen today is “green hydrogen” — produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using renewable electricity (like wind or solar). This method is clean but expensive and energy-intensive. Until green hydrogen becomes the norm, most hydrogen cars are running on a fuel that’s far from green.

Energy Losses in the Hydrogen Chain

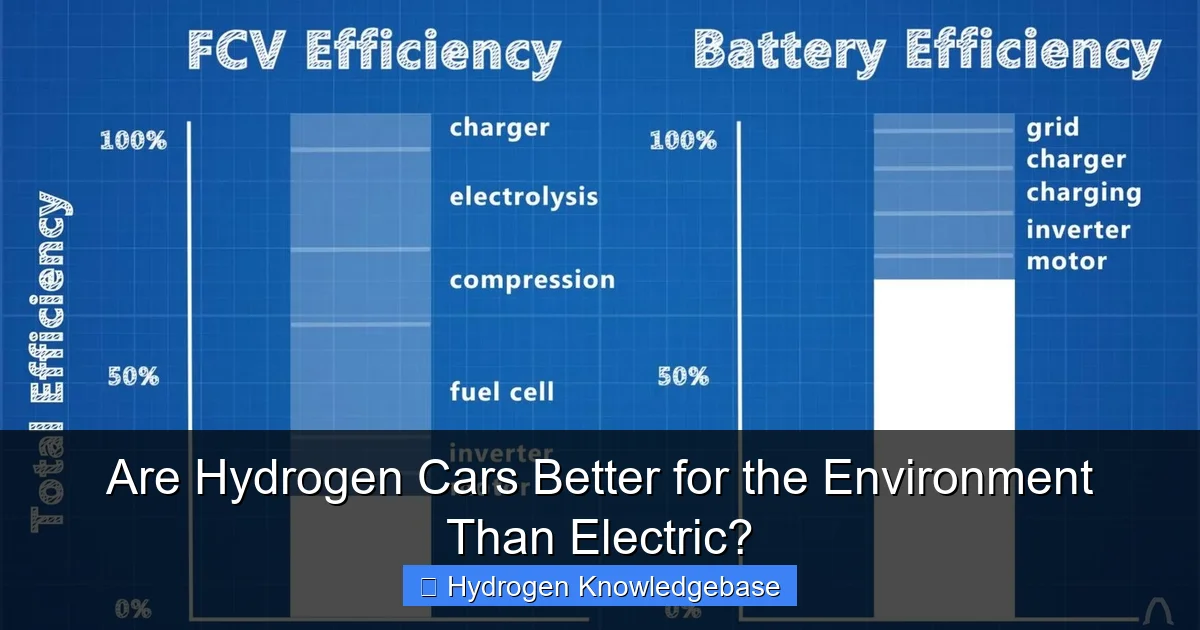

Even if green hydrogen becomes widespread, hydrogen cars face a major efficiency hurdle. The journey from renewable energy to motion in a hydrogen car involves several energy conversion steps:

1. Electricity is used to produce hydrogen via electrolysis (about 70–80% efficient).

2. The hydrogen is compressed, stored, and transported (losing another 10–15% of energy).

3. At the fuel cell, hydrogen is converted back into electricity (about 60% efficient).

4. The electricity powers the motor (about 90% efficient).

When you add it all up, only about 25–35% of the original renewable energy actually makes it to the wheels. That’s a huge loss compared to electric vehicles.

Storage and Infrastructure Challenges

Hydrogen is a tricky substance to store and transport. It’s the lightest element, which means it takes up a lot of space unless compressed or liquefied. High-pressure tanks are heavy and expensive, and hydrogen can leak easily, posing safety concerns.

Building a hydrogen refueling network is also a massive challenge. Unlike electricity, which flows through existing power grids, hydrogen requires entirely new infrastructure — production plants, pipelines, compression stations, and retail pumps. As of 2024, there are fewer than 200 hydrogen refueling stations in the entire United States, mostly in California. In contrast, there are over 150,000 public EV charging ports nationwide.

This lack of infrastructure makes hydrogen cars impractical for most drivers today, even if the technology were perfectly clean.

Electric Vehicles: Efficiency and the Grid Factor

Electric vehicles have a clear advantage when it comes to energy efficiency. An EV converts about 77% of the electrical energy from the grid to power at the wheels. That’s more than double the efficiency of hydrogen cars.

But efficiency isn’t the whole story. The environmental impact of EVs depends heavily on how the electricity they use is generated.

Grid Cleanliness Matters

If an EV is charged using electricity from coal-fired power plants, its carbon footprint increases significantly. However, as the world shifts toward renewable energy, the average carbon intensity of electricity grids is dropping. In countries like Norway, where over 90% of electricity comes from hydropower, EVs are extremely clean. Even in the U.S., where the grid is still mixed, studies show that EVs produce fewer emissions over their lifetime than gasoline cars — and the gap is widening as renewables grow.

For example, a 2023 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation (ICCT) found that the average EV in Europe emits 66–69% less CO₂ over its lifetime than a comparable gasoline car. In the U.S., the reduction is about 60–68%. These numbers will only improve as grids get cleaner.

Battery Production: The Environmental Cost

One of the biggest criticisms of EVs is the environmental impact of battery manufacturing. Producing lithium-ion batteries requires mining for lithium, cobalt, nickel, and other materials. These processes can be energy-intensive and have social and ecological consequences, especially in regions with weak environmental regulations.

However, battery technology is improving rapidly. Newer chemistries use less cobalt, and recycling programs are expanding. Companies like Redwood Materials and Li-Cycle are building large-scale battery recycling facilities to recover valuable materials and reduce the need for new mining.

Moreover, the carbon debt from battery production is typically paid back within 6–24 months of driving, depending on the local grid. After that, EVs continue to operate with very low emissions.

Charging Infrastructure and Convenience

EVs benefit from a rapidly growing charging network. Home charging is convenient and cost-effective — most EV owners charge overnight in their garage or driveway. Public fast chargers are also spreading, with companies like Tesla, Electrify America, and ChargePoint expanding coverage.

This convenience makes EVs practical for daily use, commuting, and even long trips. While charging takes longer than refueling with gasoline or hydrogen, improvements in battery technology and ultra-fast charging (10–80% in 20–30 minutes) are narrowing the gap.

Comparing Lifecycle Emissions: EVs vs. Hydrogen Cars

To truly assess environmental impact, we need to look at the full lifecycle of each vehicle — from raw material extraction and manufacturing to operation and end-of-life disposal.

Manufacturing Phase

Both EVs and hydrogen cars have higher manufacturing emissions than conventional vehicles due to their advanced technology. EVs require large batteries, while hydrogen cars need complex fuel cells and high-pressure tanks.

However, studies consistently show that EVs have a lower manufacturing footprint than hydrogen cars. A 2022 report by the Union of Concerned Scientists found that producing an EV generates about 15–68% more emissions than a gasoline car, depending on battery size. For hydrogen cars, the increase is even higher — up to 80% more — due to the energy-intensive production of fuel cells and hydrogen storage systems.

Operational Phase

This is where the biggest differences emerge. Over their lifetime, EVs typically produce far fewer emissions than hydrogen cars — unless the hydrogen is 100% green and produced with surplus renewable energy.

Let’s break it down with an example:

– A typical EV driven 150,000 miles in the U.S. emits about 50–60 metric tons of CO₂ over its lifetime (including manufacturing).

– A hydrogen car using grey hydrogen emits about 100–120 metric tons — more than a gasoline car.

– A hydrogen car using green hydrogen drops to around 40–50 metric tons, making it competitive with EVs.

But green hydrogen is still rare and expensive. Until it becomes mainstream, hydrogen cars can’t claim a clear environmental win.

End-of-Life and Recycling

Both vehicle types face challenges in recycling. EV batteries can be recycled to recover up to 95% of materials like lithium, cobalt, and nickel. Hydrogen fuel cells contain platinum, a rare and expensive metal, which can also be recovered.

However, recycling infrastructure is still developing. As demand grows, both industries are investing in closed-loop systems to minimize waste and reduce reliance on mining.

Where Hydrogen Cars Shine: Niche Applications

While hydrogen cars may not be the best choice for everyday passenger vehicles, they have strong potential in specific sectors.

Heavy-Duty and Long-Haul Transport

Trucks, buses, and trains that travel long distances or carry heavy loads face unique challenges. Batteries are heavy and take a long time to charge, making them less practical for freight transport. A Class 8 truck might need a battery weighing several tons to achieve a 500-mile range — reducing cargo capacity and increasing costs.

Hydrogen, on the other hand, offers high energy density and quick refueling. A hydrogen-powered truck can refuel in 10–15 minutes and travel 500–700 miles — similar to diesel. Companies like Nikola, Toyota, and Hyundai are developing hydrogen trucks for this reason.

Aviation and Maritime Use

Electric planes are still in early development due to battery weight limitations. Hydrogen, especially in liquid form or as a feedstock for synthetic fuels, could play a key role in decarbonizing aviation and shipping. Airbus, for example, is exploring hydrogen-powered aircraft for short-haul flights by 2035.

Energy Storage and Grid Balancing

Hydrogen isn’t just for cars. It can also store excess renewable energy. When wind or solar production is high, surplus electricity can power electrolysis to produce hydrogen, which is stored and later used in fuel cells or industrial processes. This helps balance the grid and reduce curtailment of renewables.

In this role, hydrogen supports the clean energy transition — even if it’s not always used in vehicles.

The Role of Policy and Innovation

The future of hydrogen and electric vehicles depends not just on technology, but on policy, investment, and consumer behavior.

Government Support and Incentives

Governments around the world are investing in both technologies. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits for EV purchases and funding for clean hydrogen production. The European Union has launched the Hydrogen Strategy, aiming to install 40 gigawatts of electrolyzers by 2030.

However, most incentives still favor EVs due to their maturity and scalability. Hydrogen remains a longer-term bet, requiring significant upfront investment.

Technological Breakthroughs

Innovation could change the game. Solid-state batteries promise higher energy density, faster charging, and lower costs for EVs. On the hydrogen side, advances in electrolysis, fuel cell durability, and hydrogen storage could improve efficiency and reduce costs.

Green hydrogen production is also scaling up. Projects like the HyDeal Ambition in Europe aim to produce green hydrogen at $1.50 per kilogram by 2030 — competitive with grey hydrogen today.

Consumer Adoption and Awareness

Public perception plays a big role. EVs are already familiar to many drivers, while hydrogen cars remain a novelty. Education, test drives, and visible infrastructure will be key to building trust in hydrogen technology.

Conclusion: Which Is Better for the Environment?

So, are hydrogen cars better for the environment than electric? The short answer is: not yet — and not for most people.

Electric vehicles are currently the more environmentally friendly option for passenger cars. They’re more energy-efficient, supported by cleaner grids, and backed by mature infrastructure. Their lifecycle emissions are lower, especially as battery recycling and renewable energy grow.

Hydrogen cars have potential, particularly in heavy transport and industrial applications, but they face major hurdles. Most hydrogen today is produced from fossil fuels, and the energy losses in production, storage, and conversion make them less efficient than EVs. Unless green hydrogen becomes cheap and abundant, hydrogen cars won’t outperform electric ones on environmental grounds.

That said, the future isn’t a zero-sum game. Both technologies have roles to play. EVs will likely dominate personal transportation, while hydrogen could power trucks, ships, and planes. The real winner will be the planet — if we invest wisely, prioritize renewables, and build a truly sustainable energy system.

The path to zero emissions isn’t about choosing one technology over another. It’s about using the right tool for the right job — and doing it with clean energy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is green hydrogen?

Green hydrogen is produced by splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using renewable electricity, such as wind or solar power. It emits no carbon dioxide during production and is the cleanest form of hydrogen available.

Are hydrogen cars safe?

Yes, hydrogen cars are designed with multiple safety features, including leak detection, ventilation systems, and reinforced tanks. Studies show they are as safe as conventional vehicles when properly maintained.

How many hydrogen refueling stations exist in the U.S.?

As of 2024, there are fewer than 200 hydrogen refueling stations in the U.S., with over 90% located in California. This limited network makes hydrogen cars impractical for most drivers.

Do hydrogen cars have a longer range than EVs?

Some hydrogen cars offer ranges of 300–400 miles, comparable to long-range EVs. However, real-world range depends on driving conditions, and hydrogen infrastructure limits long-distance travel.

Can existing gas stations be converted to hydrogen stations?

It’s technically possible but expensive. Hydrogen requires high-pressure storage, specialized pumps, and safety systems. Most conversions would require significant investment and regulatory approval.

What happens to hydrogen fuel cells at the end of their life?

Fuel cells contain valuable materials like platinum, which can be recovered and recycled. Recycling programs are still developing, but they offer a way to reduce waste and recover critical resources.