Hydrogen fuel cells and electric batteries both aim to cut emissions, but they differ in efficiency, refueling, and use cases. While batteries win in energy conversion, hydrogen excels in long-haul transport and quick refueling.

Key Takeaways

- Energy Efficiency: Electric batteries are 70–90% efficient, while hydrogen fuel cells average 25–35% well-to-wheel efficiency.

- Refueling Time: Hydrogen vehicles refuel in 3–5 minutes, similar to gasoline, while fast-charging batteries take 20–40 minutes.

- Range and Weight: Hydrogen-powered vehicles offer longer ranges and lighter storage, ideal for trucks and buses.

- Environmental Impact: Both are clean at the tailpipe, but battery EVs rely on grid electricity, while hydrogen’s footprint depends on production methods.

- Cost and Infrastructure: Battery charging networks are widespread; hydrogen refueling stations are limited and expensive to build.

- Best Use Cases: Batteries dominate passenger cars; hydrogen shines in aviation, shipping, and heavy industry.

- Future Outlook: Advances in green hydrogen and solid-state batteries could shift the balance in the next decade.

📑 Table of Contents

- How Efficient Are Hydrogen Fuel Cells Compared to Electric Batteries?

- Understanding the Basics: How Each Technology Works

- Efficiency Breakdown: Numbers That Matter

- Refueling and Convenience: Time Matters

- Environmental Impact: Clean at the Tailpipe, But What About the Source?

- Cost and Infrastructure: The Practical Reality

- Best Use Cases: Where Each Technology Shines

- The Road Ahead: Innovation and Trends

- Conclusion: Efficiency Isn’t Everything—But It Matters

How Efficient Are Hydrogen Fuel Cells Compared to Electric Batteries?

Imagine you’re standing at a crossroads. On one path, electric vehicles (EVs) powered by lithium-ion batteries silently glide past, charging at home or at fast stations. On the other, hydrogen-powered trucks and buses refuel in minutes, emitting nothing but water vapor. Both promise a cleaner future, but which path is more efficient?

The race between hydrogen fuel cells and electric batteries isn’t just about technology—it’s about energy, time, cost, and real-world usability. As the world pushes toward net-zero emissions, understanding the strengths and weaknesses of each system is crucial. Are hydrogen fuel cells truly a viable alternative, or are batteries the clear winner?

In this article, we’ll break down the efficiency of hydrogen fuel cells versus electric batteries, not just in theory, but in practice. We’ll explore how energy flows from source to wheel, compare refueling and range, and examine which technology fits different needs. Whether you’re a curious consumer, a fleet manager, or a policy planner, this guide will help you make sense of the clean energy puzzle.

Understanding the Basics: How Each Technology Works

Visual guide about How Efficient Are Hydrogen Fuel Cells Compared to Electric Batteries?

Image source: images.theecoexperts.co.uk

Before diving into efficiency, let’s clarify how hydrogen fuel cells and electric batteries actually work. Think of them as two different ways to store and use energy.

Electric Batteries: Storing Energy Directly

Electric batteries, like the lithium-ion ones in your phone or EV, store electrical energy chemically. When you plug in your car, electricity from the grid charges the battery. When you drive, the battery releases that stored energy to power an electric motor.

It’s a straightforward process: electricity in, electricity out. Because there are fewer energy conversions, batteries are highly efficient. Most of the energy you put in gets used to move the car—minimal waste.

Hydrogen Fuel Cells: Converting Gas to Electricity

Hydrogen fuel cells work differently. They don’t store electricity—they generate it. Hydrogen gas is fed into the fuel cell, where it reacts with oxygen from the air. This chemical reaction produces electricity, water, and heat. The electricity then powers the vehicle’s motor.

But here’s the catch: hydrogen isn’t found freely in nature. It must be produced, usually by splitting water (electrolysis) or extracting it from natural gas (steam methane reforming). Each step—production, compression, transport, and conversion—loses energy.

So while the fuel cell itself is efficient (about 60% efficient at converting hydrogen to electricity), the full “well-to-wheel” process is much less so.

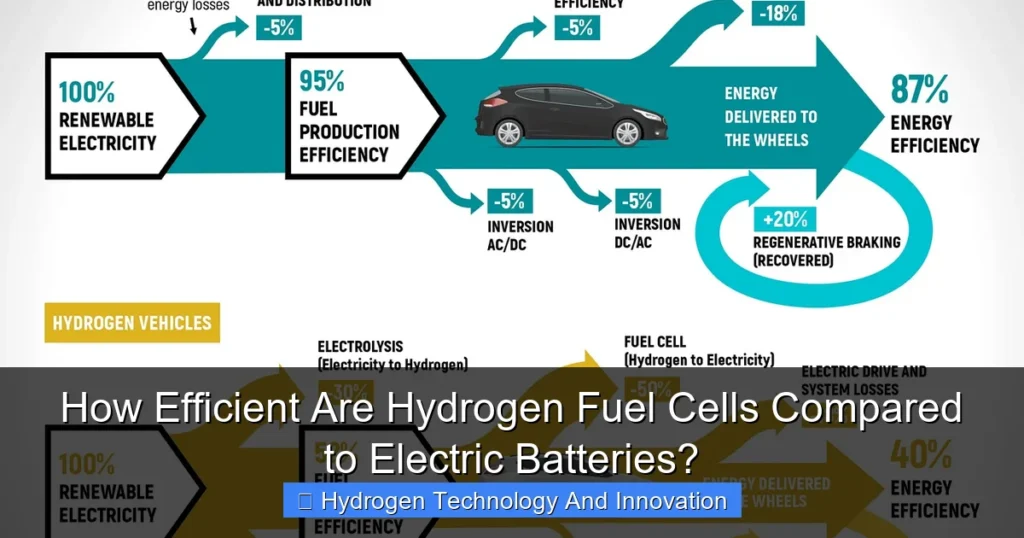

The Energy Flow: From Source to Motion

To compare efficiency fairly, we need to look at the entire energy journey—from the original energy source (like solar panels or natural gas) all the way to the wheels turning.

For electric vehicles, the path is:

– Electricity generated (e.g., from solar or wind)

– Transmitted to a charging station

– Stored in the battery

– Used to power the motor

For hydrogen vehicles, the path is longer:

– Electricity used to produce hydrogen (via electrolysis)

– Hydrogen compressed and transported

– Stored in the vehicle’s tank

– Converted back to electricity in the fuel cell

– Powers the motor

Each step introduces losses. That’s why, when you trace the energy from source to wheel, hydrogen comes out far behind batteries in overall efficiency.

Efficiency Breakdown: Numbers That Matter

Let’s get into the numbers. Efficiency isn’t just a technical detail—it affects cost, range, and environmental impact.

Well-to-Wheel Efficiency: The Full Picture

Well-to-wheel efficiency measures how much of the original energy actually moves the vehicle. It includes production, transport, storage, and conversion.

– **Electric vehicles (battery EVs):** 70–90% efficient

– **Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs):** 25–35% efficient

That’s a huge gap. For every 100 units of energy used to charge an EV, 70–90 units reach the wheels. For hydrogen, only 25–35 units make it.

Why the difference? Batteries skip multiple conversion steps. Hydrogen requires energy to produce, compress, transport, and convert—each step losing 10–30% of the energy.

Round-Trip Efficiency: Charging and Discharging

Round-trip efficiency measures how much energy is lost when storing and retrieving power.

– **Lithium-ion batteries:** 85–95% efficient

– **Hydrogen (electrolysis + fuel cell):** 30–40% efficient

If you use solar power to charge a battery, you lose only 5–15% of the energy. If you use that same solar power to make hydrogen, then convert it back to electricity, you lose 60–70%.

This makes batteries far better for storing renewable energy—whether in vehicles or on the grid.

Real-World Examples: Tesla vs. Toyota Mirai

Let’s compare two real vehicles:

– **Tesla Model 3 (battery EV):** Uses about 25 kWh per 100 miles. With a 75 kWh battery, it gets ~300 miles of range.

– **Toyota Mirai (hydrogen FCEV):** Uses about 1 kg of hydrogen per 60 miles. With a 5.6 kg tank, it gets ~300 miles.

But producing 1 kg of hydrogen via electrolysis takes about 50–55 kWh of electricity. So to go 60 miles, the Mirai uses 50+ kWh of electricity—more than double the Tesla’s 25 kWh.

Even if the hydrogen is made from renewable energy, the inefficiency means you need twice as much solar or wind power to fuel a hydrogen car.

Refueling and Convenience: Time Matters

Efficiency isn’t just about energy—it’s about time, convenience, and usability.

Refueling Speed: Minutes vs. Minutes?

One of hydrogen’s biggest selling points is fast refueling.

– **Hydrogen vehicles:** 3–5 minutes to fill up, just like gasoline.

– **Battery EVs (fast charging):** 20–40 minutes for 10–80% charge.

For long trips or commercial fleets, this is a game-changer. A delivery truck can’t wait an hour to charge—it needs to keep moving.

But fast charging is improving. New EVs like the Hyundai Ioniq 5 or Porsche Taycan can charge from 10% to 80% in under 20 minutes. And ultra-fast chargers (350 kW) are rolling out across highways.

Still, hydrogen wins on speed—for now.

Charging at Home vs. Hydrogen Stations

Most EV owners charge at home overnight. It’s cheap, convenient, and uses off-peak electricity.

Hydrogen? There are fewer than 100 public hydrogen stations in the U.S., mostly in California. You can’t install a hydrogen pump in your garage. Refueling means driving to a station—often far from home.

This limits hydrogen’s appeal for everyday drivers. But for fleets operating from a central depot, on-site hydrogen production or delivery could make sense.

Range Anxiety: How Far Can You Go?

Both technologies offer decent range.

– **Battery EVs:** 250–400+ miles (Tesla, Lucid, etc.)

– **Hydrogen FCEVs:** 300–400 miles (Toyota Mirai, Hyundai NEXO)

But cold weather affects batteries more. Lithium-ion batteries lose 20–40% range in freezing temps. Hydrogen vehicles are less impacted, making them better for cold climates.

Also, hydrogen tanks are lighter than large battery packs. For heavy vehicles like trucks or buses, this means more payload capacity.

Environmental Impact: Clean at the Tailpipe, But What About the Source?

Both hydrogen and battery EVs emit zero pollutants while driving. But the real environmental impact depends on how the energy is produced.

Green Hydrogen vs. Grid Electricity

– **Battery EVs:** Run on electricity from the grid. If your grid uses coal, your EV isn’t truly clean. But as grids get greener (more solar, wind, nuclear), EVs get cleaner too.

– **Hydrogen:** Can be “green” if made with renewable electricity (green hydrogen), “blue” if made from natural gas with carbon capture, or “gray” if made from fossil fuels without capture.

Currently, over 95% of hydrogen is gray—produced from natural gas, emitting CO₂. Green hydrogen is growing but still expensive and limited.

So while a hydrogen car emits only water, the process to make its fuel may be polluting.

Lifecycle Emissions: Manufacturing Matters

Batteries require mining lithium, cobalt, and nickel—energy-intensive processes with environmental and ethical concerns.

Hydrogen fuel cells use platinum, a rare and expensive metal. But newer designs are reducing or eliminating platinum use.

Both technologies have manufacturing footprints. But over their lifetime, EVs typically have lower total emissions—especially as grids decarbonize.

Recycling and End-of-Life

Battery recycling is advancing. Companies like Redwood Materials and Li-Cycle are recovering up to 95% of battery materials.

Hydrogen tanks and fuel cells are also recyclable, but the infrastructure is less developed.

In the long run, both can be sustainable—but batteries are further along.

Cost and Infrastructure: The Practical Reality

Efficiency and emissions matter, but so do dollars and cents.

Vehicle and Fuel Costs

– **Battery EVs:** $30,000–$100,000+. Electricity costs ~$0.10–$0.20 per kWh. A 300-mile trip costs ~$10–$15.

– **Hydrogen FCEVs:** $50,000–$70,000+. Hydrogen costs ~$12–$16 per kg. A 300-mile trip costs ~$60–$80.

Hydrogen is 4–6 times more expensive per mile than electricity. And FCEVs are pricier upfront.

Infrastructure Investment

– **EV charging:** Over 150,000 public chargers in the U.S. Home charging is free to install (with incentives). Utilities and governments are expanding fast-charging networks.

– **Hydrogen stations:** Fewer than 100 in the U.S. Each station costs $1–$2 million to build. Hydrogen transport and storage add complexity.

The U.S. Department of Energy’s H₂@Scale initiative aims to expand hydrogen infrastructure, but progress is slow.

Scalability and Energy Security

Batteries can use existing electrical grids. Adding solar panels or wind farms boosts EV sustainability.

Hydrogen requires new infrastructure: electrolyzers, pipelines, compression stations. It’s harder to scale quickly.

But hydrogen can store excess renewable energy for days or weeks—something batteries struggle with. This makes hydrogen valuable for grid stability and seasonal storage.

Best Use Cases: Where Each Technology Shines

No single technology fits all needs. The key is matching the right tool to the job.

Passenger Vehicles: Batteries Dominate

For most drivers, battery EVs are the clear choice. They’re efficient, cheaper to run, and convenient with home charging. Models like the Tesla Model Y, Ford Mustang Mach-E, and Chevrolet Bolt offer great range and performance.

Hydrogen cars like the Toyota Mirai are niche—appealing to early adopters or those in areas with hydrogen stations.

Heavy-Duty Transport: Hydrogen’s Niche

Trucks, buses, and trains benefit from hydrogen’s fast refueling and long range.

– **Trucks:** Companies like Nikola and Hyundai are testing hydrogen-powered semis for long-haul routes.

– **Buses:** Cities like London and Tokyo use hydrogen buses for zero-emission public transit.

– **Trains:** Alstom’s Coradia iLint runs on hydrogen in Germany, replacing diesel trains.

These vehicles operate on fixed routes with central refueling—perfect for hydrogen.

Aviation and Shipping: The Future Frontier

Batteries are too heavy for planes and ships. Hydrogen (especially liquid hydrogen or ammonia) is a leading candidate for decarbonizing these sectors.

– **Airbus** aims to launch a hydrogen-powered passenger plane by 2035.

– **Maersk** is investing in green ammonia (made from hydrogen) for cargo ships.

These industries need energy-dense fuels—something batteries can’t provide.

Industrial and Grid Applications

Hydrogen can power steel mills, chemical plants, and data centers. It can also store surplus renewable energy for weeks—helping balance the grid.

Batteries are better for short-term storage (hours), while hydrogen excels at long-duration storage.

The Road Ahead: Innovation and Trends

The efficiency gap between hydrogen and batteries may narrow—but slowly.

Advances in Hydrogen Technology

– **Green hydrogen:** Costs are falling. The Inflation Reduction Act offers $3/kg tax credits for clean hydrogen, making it competitive.

– **Solid oxide fuel cells:** More efficient and can use multiple fuels.

– **Ammonia and liquid organic carriers:** Easier to transport than pure hydrogen.

If green hydrogen becomes cheap and abundant, FCEVs could become more viable.

Battery Breakthroughs

– **Solid-state batteries:** Higher energy density, faster charging, safer. Toyota and QuantumScape aim for 2027–2030 production.

– **Silicon anodes and lithium-sulfur:** Could double range and reduce costs.

– **Recycling and second-life use:** Old EV batteries can power homes or grids.

These innovations will boost battery efficiency and sustainability.

Policy and Market Forces

Governments are investing in both technologies.

– The U.S. National Clean Hydrogen Strategy aims for 10 million tons of clean hydrogen by 2030.

– The EU’s Fit for 55 plan supports EVs and hydrogen infrastructure.

– China leads in EV production and is expanding hydrogen pilots.

Market adoption will depend on cost, infrastructure, and consumer choice.

Conclusion: Efficiency Isn’t Everything—But It Matters

So, how efficient are hydrogen fuel cells compared to electric batteries? The answer is clear: batteries are far more efficient—often 2–3 times more—from energy source to motion.

But efficiency isn’t the only factor. Refueling speed, range, weight, and use case matter too. For daily driving and passenger cars, batteries win on efficiency, cost, and convenience. For heavy transport, aviation, and long-duration storage, hydrogen offers unique advantages.

The future isn’t about choosing one over the other. It’s about using the right tool for the job. Batteries will dominate personal mobility. Hydrogen will power the hard-to-electrify sectors.

As technology improves and infrastructure grows, both will play key roles in a clean energy future. The goal isn’t to pick a winner—it’s to build a smarter, more sustainable system.

Whether you’re buying a car, managing a fleet, or shaping policy, understanding these differences helps you make better decisions. The road to zero emissions has many paths. Efficiency lights the way—but so do innovation, investment, and intention.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are hydrogen fuel cells more efficient than batteries?

No, hydrogen fuel cells are significantly less efficient than electric batteries. While batteries are 70–90% efficient from source to wheel, hydrogen fuel cells average only 25–35% due to energy losses in production, compression, and conversion.

Why are hydrogen vehicles less efficient?

Hydrogen requires multiple energy-intensive steps: producing hydrogen via electrolysis, compressing and transporting it, and converting it back to electricity in the fuel cell. Each step loses energy, reducing overall efficiency.

Can hydrogen ever be as efficient as batteries?

Unlikely in passenger vehicles, but advances in green hydrogen production and fuel cell technology could improve efficiency. However, batteries will likely remain more efficient for most applications due to fewer conversion steps.

Is hydrogen better for long-haul trucking?

Yes, hydrogen’s fast refueling and lighter weight make it better suited for long-haul trucks and buses, where downtime and payload matter. Batteries are heavier and take longer to charge.

What’s the environmental impact of hydrogen vs. batteries?

Both are clean at the tailpipe, but batteries rely on grid electricity (which is getting greener), while most hydrogen is currently made from fossil fuels. Green hydrogen, made with renewables, is cleaner but still less efficient.

Will hydrogen replace electric batteries?

No, hydrogen won’t replace batteries. Instead, the two will complement each other—batteries for cars and short-term storage, hydrogen for heavy transport, aviation, and long-duration energy storage.