Hydrogen cars offer a promising path toward sustainable transportation by producing zero tailpipe emissions and leveraging clean energy. While challenges like infrastructure and production methods remain, advancements in green hydrogen and fuel cell technology are accelerating their potential as a key player in the green mobility revolution.

Imagine driving a car that runs on clean energy, refuels in minutes, and leaves behind nothing but water vapor. No smog, no noise, no guilt. That’s the promise of hydrogen cars—vehicles powered by hydrogen fuel cells that generate electricity on board, emitting only pure H₂O. As the world races to cut carbon emissions and combat climate change, hydrogen technology is emerging as a powerful contender in the sustainable transportation race. While electric vehicles (EVs) dominate headlines, hydrogen-powered cars offer a different, complementary solution—especially for long-haul travel, heavy transport, and regions with limited charging infrastructure.

But are hydrogen cars truly sustainable? That’s the million-dollar question. The answer isn’t black and white. It depends on how the hydrogen is made, how efficiently it’s used, and whether the supporting systems—like refueling stations and renewable energy grids—can scale up in time. Unlike battery electric vehicles, which store energy in large batteries, hydrogen cars generate electricity through a chemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen inside a fuel cell. This process is clean at the tailpipe, but the sustainability of the entire lifecycle hinges on the source of the hydrogen itself.

Key Takeaways

- Zero tailpipe emissions: Hydrogen cars emit only water vapor, making them environmentally friendly during operation.

- Green hydrogen is key: Sustainability depends on producing hydrogen using renewable energy sources like wind and solar.

- Faster refueling than EVs: Hydrogen vehicles can refuel in 3–5 minutes, similar to gasoline cars, offering convenience for long-distance travel.

- Limited infrastructure: Currently, hydrogen refueling stations are scarce, especially outside major urban areas.

- High upfront costs: Fuel cell vehicles are more expensive than battery electric vehicles due to complex technology and low production scale.

- Heavy-duty applications shine: Hydrogen excels in trucks, buses, and industrial vehicles where battery weight and charging time are limiting factors.

- Government support is growing: Countries like Japan, Germany, and South Korea are investing heavily in hydrogen infrastructure and innovation.

📑 Table of Contents

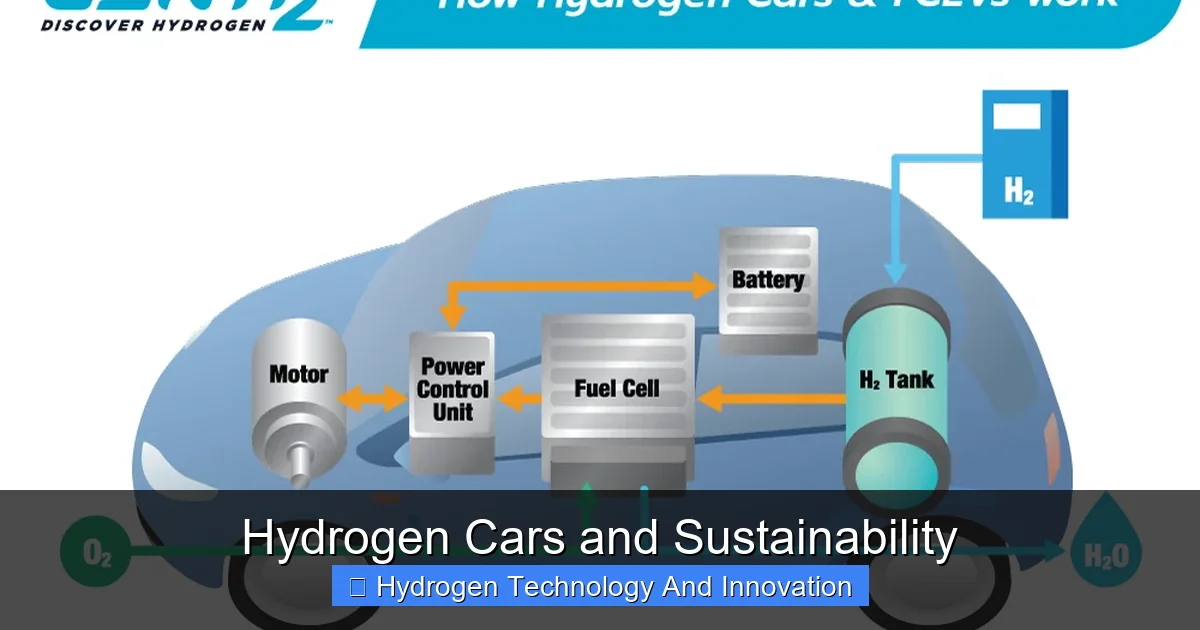

How Hydrogen Cars Work

At the heart of every hydrogen car is a fuel cell stack—a compact, high-tech engine that converts hydrogen gas into electricity. Here’s how it works in simple terms: hydrogen from the car’s tank flows into the fuel cell, where it splits into protons and electrons. The protons pass through a membrane, while the electrons are forced to travel through an external circuit, creating an electric current. This electricity powers the car’s motor. Meanwhile, oxygen from the air enters the fuel cell and combines with the protons and electrons to form water—the only byproduct.

This process is incredibly efficient and quiet. Unlike internal combustion engines, which waste a lot of energy as heat, fuel cells convert up to 60% of the energy in hydrogen into usable power. Compare that to gasoline engines, which typically operate at around 20–30% efficiency, and the advantage becomes clear.

Types of Hydrogen Fuel Cells

Not all fuel cells are the same. The most common type used in vehicles is the Proton Exchange Membrane Fuel Cell (PEMFC). It operates at relatively low temperatures (around 80°C), starts quickly, and is compact—perfect for cars and buses. Other types, like Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFC), are better suited for stationary power generation due to their high operating temperatures.

PEMFCs use a thin plastic membrane coated with a platinum-based catalyst. While platinum is expensive and rare, researchers are working to reduce or replace it with cheaper materials. Recent advances have cut platinum usage by over 80%, helping to lower costs and improve sustainability.

Hydrogen Storage: A Technical Challenge

Storing hydrogen safely and efficiently is one of the biggest engineering hurdles. Hydrogen is the lightest element and highly flammable, so it must be compressed or liquefied for use in vehicles. Most hydrogen cars store gas in high-strength carbon-fiber tanks at pressures of 700 bar (over 10,000 psi). These tanks are designed to withstand crashes and leaks, but they add weight and cost.

Liquid hydrogen is another option, but it requires cryogenic temperatures (-253°C), which demands heavy insulation and energy-intensive cooling. For now, compressed gas is the preferred method for passenger vehicles, while liquid hydrogen is more common in aerospace and some heavy-duty applications.

The Sustainability Equation: Green vs. Gray Hydrogen

Visual guide about Hydrogen Cars and Sustainability

Image source: genh2hydrogen.com

Here’s where the sustainability of hydrogen cars gets complicated. Not all hydrogen is created equal. The environmental impact depends entirely on how it’s produced.

Currently, about 95% of hydrogen is made from fossil fuels—primarily natural gas—through a process called steam methane reforming (SMR). This method releases carbon dioxide, making it far from clean. This “gray hydrogen” undermines the environmental benefits of hydrogen cars, especially when compared to battery EVs powered by renewable energy.

But there’s a cleaner alternative: green hydrogen. This is hydrogen produced using renewable electricity—like wind, solar, or hydropower—to split water into hydrogen and oxygen via electrolysis. The process emits no greenhouse gases, making it truly sustainable. When green hydrogen powers a fuel cell vehicle, the entire lifecycle—from production to driving—can be nearly carbon-free.

The Rise of Green Hydrogen

Green hydrogen is still a small fraction of global production, but it’s growing fast. Countries like Germany, Australia, and Chile are investing billions in electrolyzer plants and renewable energy projects to scale up green hydrogen. The European Union’s Hydrogen Strategy aims to install 40 gigawatts of electrolyzers by 2030, enough to produce 10 million tons of green hydrogen annually.

In the U.S., the Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits for clean hydrogen production, incentivizing companies to shift toward renewable-powered electrolysis. Similarly, Japan and South Korea are building hydrogen economies, with plans to import green hydrogen from Australia and the Middle East.

Blue Hydrogen: A Middle Ground?

Some argue that “blue hydrogen”—produced from natural gas but with carbon capture and storage (CCS)—can be a transitional solution. While it reduces emissions compared to gray hydrogen, it’s not zero-carbon. Critics point out that CCS is expensive, energy-intensive, and not yet deployed at scale. Moreover, methane leaks during natural gas extraction can offset the climate benefits.

For true sustainability, green hydrogen is the gold standard. But until it becomes widely available and affordable, blue hydrogen may play a role in bridging the gap.

Environmental Benefits and Limitations

Hydrogen cars shine in several environmental areas. First and foremost, they produce zero tailpipe emissions. Unlike gasoline or diesel vehicles, they don’t release nitrogen oxides (NOx), particulate matter, or carbon dioxide while driving. This makes them ideal for improving air quality in cities, where pollution from vehicles contributes to respiratory diseases and climate change.

They also offer energy diversification. Hydrogen can be produced domestically from renewable sources, reducing dependence on imported oil. This enhances energy security and supports local job creation in clean energy sectors.

Energy Efficiency: A Trade-Off

However, hydrogen cars are less energy-efficient than battery electric vehicles. The well-to-wheel efficiency—the total energy used from production to propulsion—is around 30–35% for hydrogen cars, compared to 70–80% for EVs. This is because producing, compressing, transporting, and converting hydrogen into electricity involves multiple energy losses.

For example, generating electricity from solar panels, using it to produce hydrogen via electrolysis, compressing and transporting the gas, and then converting it back to electricity in a fuel cell results in significant energy waste. In contrast, charging a battery EV directly from the grid is far more efficient.

This doesn’t mean hydrogen cars are useless—just that they’re better suited for specific applications where batteries fall short.

Lifecycle Emissions Matter

A full lifecycle analysis (LCA) considers emissions from manufacturing, fuel production, vehicle use, and disposal. Studies show that hydrogen cars powered by green hydrogen have lifecycle emissions similar to or lower than battery EVs, especially in regions with clean electricity grids.

But if the hydrogen comes from fossil fuels, the emissions can be higher than even gasoline cars. This underscores the importance of clean production methods.

Infrastructure and Accessibility

One of the biggest barriers to hydrogen car adoption is infrastructure. Unlike electric charging stations, which are becoming common in homes, workplaces, and public areas, hydrogen refueling stations are rare and expensive to build.

As of 2024, there are fewer than 1,000 hydrogen refueling stations worldwide, with most concentrated in California, Japan, Germany, and South Korea. In the U.S., California leads with over 60 stations, but many are clustered in Los Angeles and the Bay Area. Rural and suburban areas have little to no access.

Building a Hydrogen Network

Expanding infrastructure requires massive investment. A single hydrogen station can cost $1–2 million to build, compared to $50,000–$100,000 for a fast EV charger. The high cost is due to the need for high-pressure storage, safety systems, and specialized equipment.

Governments and private companies are working to close the gap. Toyota, Hyundai, and Honda have partnered with energy firms to build stations. In Europe, the H2ME project aims to deploy 300 stations across eight countries by 2025. Australia is developing a hydrogen highway along its east coast, targeting long-haul trucking routes.

Home Refueling: A Future Possibility?

Imagine refueling your hydrogen car at home, just like charging an EV. While technically possible, home hydrogen refueling is not yet practical. Small-scale electrolyzers exist, but they’re expensive and require a reliable source of renewable electricity. Safety concerns and regulatory hurdles also limit adoption.

For now, centralized stations are the norm. But as technology improves and costs fall, decentralized hydrogen production could become viable—especially in remote areas with abundant solar or wind power.

Cost and Market Adoption

Hydrogen cars are still a niche market. As of 2024, global sales are in the tens of thousands, compared to over 10 million EVs sold annually. The main reason? Cost.

The Toyota Mirai and Hyundai NEXO, the two most popular hydrogen cars, start around $60,000–$70,000—significantly more than comparable EVs like the Tesla Model 3 or Hyundai Ioniq 5. High costs stem from expensive fuel cells, platinum catalysts, and low production volumes.

Total Cost of Ownership

While the upfront price is high, operating costs can be lower. Hydrogen fuel is currently expensive—around $16 per kilogram in the U.S., which translates to about $0.12–$0.15 per mile. That’s more than electricity for EVs ($0.04–$0.08 per mile) but less than gasoline in many regions.

However, hydrogen prices are expected to drop as production scales up. The U.S. Department of Energy aims to reduce the cost of green hydrogen to $1 per kilogram by 2031—a goal known as the “Hydrogen Shot.” If achieved, hydrogen could become competitive with gasoline and electricity.

Leasing and Incentives

To boost adoption, manufacturers often include free hydrogen fuel for several years with vehicle leases. In California, buyers can receive up to $15,000 in state and federal incentives. Similar programs exist in Japan and Europe.

But without broader infrastructure and lower costs, mass-market adoption will remain a challenge.

Hydrogen Beyond Passenger Cars

While hydrogen cars grab attention, the real promise of hydrogen may lie in heavier applications. Buses, trucks, trains, ships, and even airplanes are exploring hydrogen as a clean fuel.

Heavy-Duty Transport

Battery electric trucks face limitations: heavy batteries reduce payload, and long charging times disrupt logistics. Hydrogen fuel cells offer a solution. They’re lighter, refuel faster, and provide longer range—ideal for freight and delivery.

Companies like Nikola, Hyundai, and Toyota are developing hydrogen-powered trucks. In Europe, the H2Haul project is testing hydrogen trucks in real-world conditions. In California, the Port of Long Beach is piloting hydrogen drayage trucks to reduce emissions from cargo transport.

Public Transit and Aviation

Hydrogen buses are already in service in cities like London, Aberdeen, and Tokyo. They offer zero emissions and quiet operation, improving urban air quality.

In aviation, startups like ZeroAvia and Airbus are working on hydrogen-powered planes. While still in early stages, hydrogen could enable short-haul flights with zero emissions—something batteries can’t yet achieve due to weight constraints.

The Road Ahead: Challenges and Opportunities

The future of hydrogen cars depends on overcoming key challenges: cost, infrastructure, and clean production. But the opportunities are vast.

Policy and Investment

Government support is critical. Countries investing in hydrogen include:

– Japan: Aiming for 800,000 hydrogen vehicles by 2030.

– Germany: Building a national hydrogen network with 100 stations by 2025.

– South Korea: Targeting 200,000 hydrogen cars and 600 stations by 2030.

– U.S.: The Bipartisan Infrastructure Law includes $8 billion for hydrogen hubs.

These investments could accelerate innovation and drive down costs.

Technological Breakthroughs

Researchers are exploring alternatives to platinum catalysts, such as iron-nitrogen-carbon materials, which could slash fuel cell costs. New electrolyzer designs are improving efficiency and durability. Solid-state hydrogen storage could make tanks safer and lighter.

If these advances succeed, hydrogen cars could become more affordable and practical.

A Complementary Future

Hydrogen won’t replace battery EVs—it will complement them. For short commutes and urban driving, EVs are ideal. For long-distance travel, heavy transport, and regions with limited charging, hydrogen offers a viable alternative.

A sustainable transportation future will likely include both technologies, each playing to its strengths.

Conclusion

Hydrogen cars represent a bold step toward sustainable mobility. With zero tailpipe emissions, fast refueling, and the potential for clean energy integration, they offer a compelling vision for a greener future. But their sustainability hinges on one critical factor: the source of hydrogen. Only green hydrogen—produced from renewables—can deliver on the promise of true environmental benefits.

While challenges remain—high costs, limited infrastructure, and energy inefficiencies—the momentum is growing. Governments, automakers, and energy companies are investing in hydrogen technology, recognizing its role in decarbonizing transport, especially in sectors where batteries fall short.

As innovation continues and green hydrogen becomes more accessible, hydrogen cars could transition from niche curiosities to mainstream solutions. They may not dominate the roads like EVs, but they’ll play a vital role in a diversified, sustainable transportation ecosystem. The journey is just beginning, but the destination—cleaner air, lower emissions, and energy independence—is worth the ride.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are hydrogen cars really zero-emission?

Yes, hydrogen cars produce only water vapor as a byproduct during operation. However, the overall environmental impact depends on how the hydrogen is produced. If made from fossil fuels, emissions occur upstream.

How long does it take to refuel a hydrogen car?

Refueling a hydrogen car takes about 3–5 minutes, similar to gasoline vehicles. This is much faster than charging most electric vehicles, making hydrogen convenient for long trips.

Can I refuel a hydrogen car at home?

Currently, home refueling is not practical due to high costs, safety concerns, and lack of small-scale infrastructure. Most drivers rely on public hydrogen stations.

Are hydrogen cars safe?

Yes, hydrogen cars are designed with multiple safety features, including leak detection, ventilation systems, and crash-resistant tanks. Hydrogen disperses quickly in air, reducing fire risk compared to gasoline.

Why aren’t hydrogen cars more popular?

High costs, limited refueling stations, and competition from electric vehicles have slowed adoption. However, growing investment and technological advances may change this in the coming years.

Will hydrogen cars replace electric vehicles?

Unlikely. Hydrogen and battery electric vehicles serve different needs. EVs are better for short-range, urban driving, while hydrogen excels in long-haul and heavy-duty applications. Both will likely coexist in a sustainable transport future.