Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) use clean hydrogen to generate electricity onboard, emitting only water vapor. They offer fast refueling and long range, making them a promising alternative to battery electric vehicles for sustainable transportation.

Imagine driving a car that runs on hydrogen, refuels in minutes, travels hundreds of miles, and leaves behind nothing but water droplets. No smog, no engine noise, no long waits at charging stations. That’s not science fiction—it’s hydrogen fuel cell vehicle technology in action. While electric vehicles (EVs) have dominated the clean transportation conversation, hydrogen-powered cars are quietly emerging as a powerful alternative with unique advantages.

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles, or FCEVs, use a chemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen to produce electricity, which powers an electric motor. Unlike battery electric vehicles that store energy in large, heavy batteries, FCEVs generate their own electricity on demand. This means they can travel farther and refuel faster—two major pain points for current EV owners. And because the only byproduct is water vapor, FCEVs are among the cleanest vehicles on the road today.

But how exactly does this technology work? And why isn’t every car on the highway running on hydrogen? In this guide, we’ll break down the science, explore the benefits and challenges, and look at real-world applications of hydrogen fuel cell vehicle technology. Whether you’re a curious driver, a tech enthusiast, or someone planning a greener future, understanding FCEVs is essential in the evolving landscape of sustainable mobility.

Key Takeaways

- Zero tailpipe emissions: Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles produce only water vapor as exhaust, making them truly clean on the road.

- Fast refueling: FCEVs can be refueled in 3–5 minutes, similar to gasoline cars, unlike battery EVs that take 30+ minutes even with fast chargers.

- Long driving range: Most hydrogen cars offer 300–400 miles per tank, ideal for long-distance travel and commercial use.

- Onboard electricity generation: Unlike battery EVs, FCEVs generate power as they drive using a fuel cell stack, not just stored energy.

- Green hydrogen potential: When produced using renewable energy, hydrogen becomes a fully sustainable fuel source.

- Infrastructure challenges: Limited hydrogen refueling stations remain a barrier, though expansion is growing in key regions.

- Ideal for heavy transport: FCEVs are especially suited for trucks, buses, and trains where battery weight and charging time are limiting factors.

📑 Table of Contents

How Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles Work

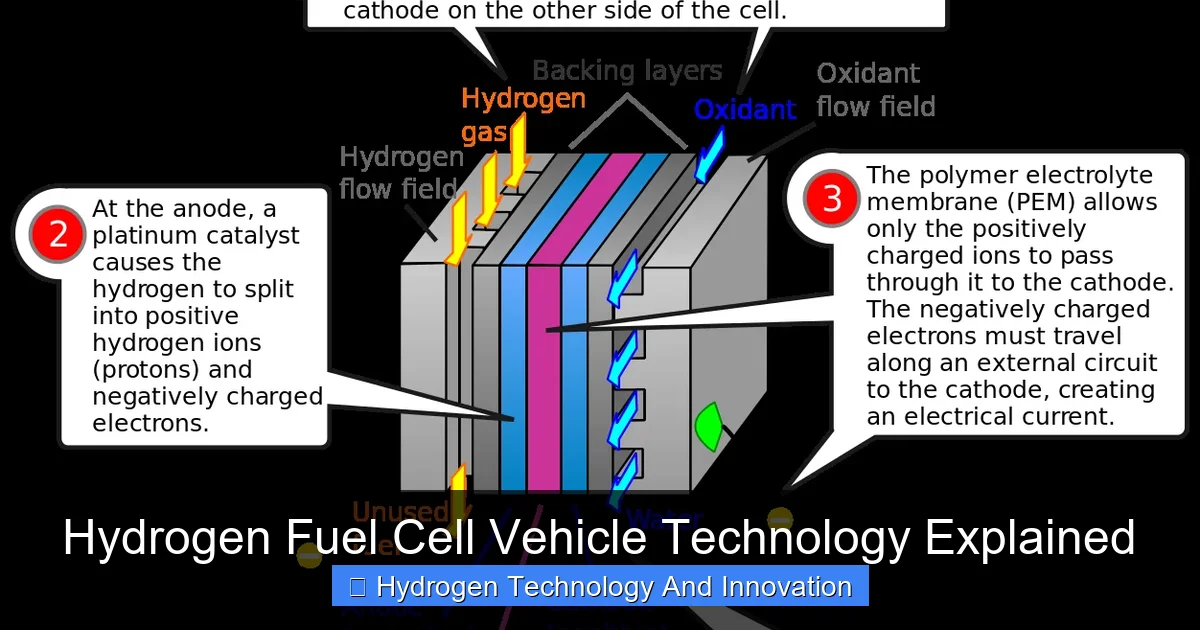

At the heart of every hydrogen fuel cell vehicle is the fuel cell stack—a compact, high-tech system that converts hydrogen into electricity. Think of it as a mini power plant under your hood. The process begins when compressed hydrogen gas is fed from the vehicle’s onboard tank into the fuel cell. Inside the stack, hydrogen molecules are split into protons and electrons using a catalyst, typically platinum. The protons pass through a special membrane, while the electrons are forced to travel through an external circuit, creating an electric current. This electricity powers the car’s motor and recharges a small auxiliary battery used for acceleration and startup.

Meanwhile, oxygen from the air enters the fuel cell and combines with the protons and electrons on the other side of the membrane, forming water—H₂O—as the only emission. This entire reaction happens silently and continuously as long as hydrogen and oxygen are supplied. The result? A smooth, quiet, and emission-free driving experience.

The Role of the Fuel Cell Stack

The fuel cell stack is the engine of an FCEV. It’s made up of hundreds of individual fuel cells layered together, each about the thickness of a credit card. These layers work in parallel to generate enough power—typically between 100 and 150 kilowatts—to move a passenger car. Modern stacks are highly efficient, converting over 60% of the hydrogen’s energy into electricity, compared to about 20–30% for internal combustion engines.

Manufacturers like Toyota, Hyundai, and Honda have spent decades refining this technology. For example, the Toyota Mirai uses a proprietary fuel cell system that’s not only powerful but also durable, designed to last over 100,000 miles with minimal degradation. The stack is also compact, fitting neatly under the floor of the car, which helps maintain interior space and balance.

Hydrogen Storage and Safety

Storing hydrogen safely is one of the biggest engineering challenges—and achievements—in FCEV design. Hydrogen is the lightest and smallest molecule, which makes it prone to leakage and requires high-pressure containment. Most hydrogen cars store fuel in carbon-fiber-reinforced tanks at 700 bar (over 10,000 psi), about three times the pressure of a scuba tank.

These tanks are rigorously tested for safety. They’re designed to withstand extreme impacts, fires, and punctures. In fact, hydrogen tanks are often safer than gasoline tanks in collisions because hydrogen disperses quickly into the atmosphere, unlike liquid fuels that can pool and ignite. Plus, modern FCEVs are equipped with multiple sensors that detect leaks and automatically shut off the hydrogen supply if needed.

Electric Motor and Energy Management

Like battery EVs, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles use electric motors for propulsion. But instead of drawing power from a large battery pack, the motor is primarily powered by the fuel cell. A small lithium-ion battery, similar to those in hybrids, assists during acceleration and stores energy from regenerative braking. This hybrid approach improves efficiency and responsiveness.

The energy management system constantly balances power between the fuel cell and battery, ensuring optimal performance and longevity. For instance, during highway cruising, the fuel cell operates steadily at peak efficiency. When accelerating or climbing hills, the battery provides a burst of extra power. This smart integration makes FCEVs both efficient and fun to drive.

Environmental Benefits of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles

Visual guide about Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicle Technology Explained

Image source: 3.bp.blogspot.com

One of the strongest arguments for hydrogen fuel cell vehicle technology is its environmental impact—or lack thereof. When you drive an FCEV, the only thing coming out of the tailpipe is water vapor. No carbon dioxide (CO₂), no nitrogen oxides (NOx), no particulate matter. That means cleaner air in cities and a direct reduction in greenhouse gas emissions from transportation, which accounts for nearly a quarter of global CO₂ output.

But the full environmental picture depends on how the hydrogen is produced. Currently, about 95% of hydrogen is made from natural gas through a process called steam methane reforming, which does release CO₂. This “gray hydrogen” undermines the green promise of FCEVs. However, the shift toward “green hydrogen”—produced using renewable energy like wind or solar to split water via electrolysis—is gaining momentum.

Green Hydrogen: The Sustainable Future

Green hydrogen is the holy grail of clean energy. When renewable electricity powers the electrolysis of water (H₂O → H₂ + O₂), the resulting hydrogen is completely carbon-free. Countries like Germany, Japan, and Australia are investing billions in green hydrogen infrastructure. For example, Australia’s Asian Renewable Energy Hub aims to produce over 1 million tons of green hydrogen annually by 2030, much of it for export.

When FCEVs run on green hydrogen, their lifecycle emissions are comparable to or even lower than battery EVs, especially in regions where electricity grids are still coal-dependent. This makes hydrogen a versatile tool in the global decarbonization toolkit.

Lifecycle Emissions Compared to EVs

Critics often point out that battery EVs have lower lifecycle emissions because they don’t require energy-intensive hydrogen production. While this is true in areas with clean electricity, the balance shifts in regions with fossil-heavy grids. A 2022 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation found that FCEVs powered by green hydrogen can have 30–50% lower lifecycle emissions than battery EVs in countries like Poland or India.

Moreover, hydrogen production can be decentralized. Solar panels on a warehouse roof can generate electricity to make hydrogen on-site, reducing transmission losses and grid strain. This flexibility is a major advantage over centralized battery charging networks.

Water Usage and Resource Efficiency

A common misconception is that hydrogen cars waste water. In reality, the amount of water used in hydrogen production is minimal compared to other industries. Producing one kilogram of hydrogen via electrolysis requires about 9 liters of water—less than what’s used to manufacture a single smartphone. And since FCEVs emit water vapor, they actually return moisture to the atmosphere, completing a natural cycle.

As for materials, fuel cells use small amounts of platinum, but recycling programs and catalyst innovations are reducing reliance on rare metals. Meanwhile, hydrogen tanks use advanced composites that are lighter and more durable than steel, improving overall vehicle efficiency.

Performance and Practical Advantages

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles aren’t just clean—they’re also practical. One of the biggest frustrations with current EVs is charging time. Even with fast chargers, topping up a battery can take 30 minutes or more. With hydrogen, refueling is as quick as pumping gas—typically 3 to 5 minutes for a full tank. That’s a game-changer for long road trips, ride-sharing services, and commercial fleets.

Refueling Speed and Convenience

Imagine pulling into a hydrogen station, connecting a nozzle, and walking away five minutes later with a full tank. No waiting, no range anxiety. This speed makes FCEVs ideal for high-mileage drivers, taxi services, and delivery companies. For example, Toyota’s fuel cell buses in Tokyo can complete full-day routes with just one midday refuel.

Refueling is also simple and safe. The process is automated, with safety locks and leak detection built into the dispenser. Drivers don’t need to handle the hydrogen directly—just like at a gas station.

Driving Range and Efficiency

Most hydrogen cars offer a range of 300 to 400 miles on a single tank, comparable to gasoline vehicles and significantly better than many EVs. The Hyundai NEXO, for instance, boasts an EPA-estimated range of 380 miles. This makes FCEVs suitable for rural areas, cross-country travel, and regions with sparse charging infrastructure.

While hydrogen is less energy-efficient than batteries (due to losses in production, compression, and conversion), the high energy density of hydrogen compensates for this. A kilogram of hydrogen contains about three times more energy than a kilogram of gasoline, allowing for longer range without heavy batteries.

Quiet and Smooth Operation

Like all electric vehicles, FCEVs are whisper-quiet and offer instant torque for smooth acceleration. There’s no engine vibration, no gear shifts, and no noise pollution. This makes for a serene driving experience, especially in urban environments. Plus, the absence of combustion means no heat buildup, reducing the need for complex cooling systems.

Challenges and Limitations

Despite their promise, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles face significant hurdles. The biggest barrier is infrastructure. As of 2024, there are fewer than 200 public hydrogen refueling stations in the United States, mostly concentrated in California. In contrast, there are over 150,000 public EV charging ports nationwide. Without a reliable network, consumers are hesitant to adopt FCEVs.

Limited Refueling Infrastructure

Building hydrogen stations is expensive—each one costs $1–2 million, compared to $50,000–$100,000 for a fast EV charger. Stations require high-pressure storage, safety systems, and specialized equipment. Plus, hydrogen must be delivered by truck or pipeline, adding logistical complexity.

However, governments and private companies are investing in expansion. California plans to have 200 stations by 2025, and Europe is rolling out hydrogen corridors along major highways. Japan and South Korea are also leading in infrastructure development, with over 150 stations each.

High Production and Distribution Costs

Green hydrogen is still expensive to produce—around $4–6 per kilogram, compared to $1–2 for gray hydrogen. This makes FCEVs costlier to operate than gasoline or even battery EVs. However, costs are expected to drop as electrolyzer technology improves and renewable energy becomes cheaper. The U.S. Department of Energy aims to reduce green hydrogen costs to $1 per kilogram by 2030.

Distribution is another challenge. Hydrogen is difficult to transport due to its low density and high flammability. Liquefying it requires cooling to -253°C, which is energy-intensive. Most hydrogen is currently delivered by tube trailers, but pipelines and ammonia carriers are being explored for long-distance transport.

Public Perception and Awareness

Many people still associate hydrogen with the Hindenburg disaster, despite modern safety advances. Education is key to changing perceptions. Automakers are working to highlight the safety, reliability, and environmental benefits of FCEVs. Test drives, public demos, and partnerships with fleets can help build trust.

Real-World Applications and Success Stories

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles aren’t just prototypes—they’re already on the road. Toyota’s Mirai, launched in 2014, has sold over 20,000 units worldwide. Hyundai’s NEXO has won multiple awards for its design and efficiency. And in commercial sectors, FCEVs are proving their worth.

Passenger Cars: Mirai and NEXO

The Toyota Mirai is one of the most advanced FCEVs available. The second-generation model features a sleeker design, improved range (402 miles), and a more efficient fuel cell system. It’s available in select markets, including California, Japan, and parts of Europe. Hyundai’s NEXO offers similar performance with a focus on luxury and safety, earning a 5-star Euro NCAP rating.

Commercial and Heavy-Duty Vehicles

Where FCEVs truly shine is in heavy transport. Buses, trucks, and trains benefit from hydrogen’s high energy density and fast refueling. For example, the city of Aberdeen, Scotland, operates a fleet of hydrogen buses that have logged over 2 million miles. In the U.S., companies like Nikola and Hyzon are developing hydrogen-powered semi-trucks for long-haul freight.

Trains are another promising application. Alstom’s Coradia iLint, a hydrogen-powered passenger train, operates in Germany and emits only steam and condensed water. It can travel up to 620 miles on a single tank, making it ideal for non-electrified rail lines.

Industrial and Backup Power

Beyond transportation, fuel cells are used in warehouses for forklifts, in data centers for backup power, and in remote areas for off-grid electricity. Amazon and Walmart use hydrogen forklifts in their distribution centers because they refuel in minutes and don’t require charging downtime.

The Future of Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicle Technology

The future of hydrogen fuel cell vehicle technology is bright, but it will take time, investment, and collaboration. Governments are setting ambitious targets: the European Union aims for 10 million tons of renewable hydrogen by 2030, while the U.S. has launched the Hydrogen Shot initiative to cut costs by 80%.

Innovation in Fuel Cell Design

Researchers are developing next-gen fuel cells that use less platinum, operate at lower temperatures, and last longer. Solid oxide fuel cells (SOFCs) and proton exchange membrane (PEM) improvements are pushing efficiency beyond 70%. New catalysts made from non-precious metals could drastically reduce costs.

Integration with Renewable Energy

Hydrogen can act as a “green battery,” storing excess solar and wind energy for later use. Excess electricity from a wind farm can power electrolyzers to produce hydrogen, which is then stored and used to generate power when the wind isn’t blowing. This creates a flexible, resilient energy system.

Global Expansion and Policy Support

Countries are forming hydrogen alliances to share technology and build infrastructure. Japan’s “Basic Hydrogen Strategy” and South Korea’s “Hydrogen Economy Roadmap” are leading the way. In the U.S., the Inflation Reduction Act offers tax credits for clean hydrogen production, accelerating adoption.

As the technology matures and costs fall, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles could become a mainstream option—especially for long-range, high-utilization applications. While battery EVs will dominate personal urban transport, FCEVs will likely play a critical role in decarbonizing freight, aviation, and heavy industry.

Conclusion

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicle technology represents a bold step toward a cleaner, more sustainable transportation future. With zero emissions, fast refueling, and long range, FCEVs offer a compelling alternative to both gasoline cars and battery EVs. While challenges remain—especially in infrastructure and cost—the progress made in recent years is undeniable.

From passenger cars like the Toyota Mirai to hydrogen-powered buses and trains, real-world applications are proving the technology’s viability. And as green hydrogen production scales up, the environmental benefits will only grow. The road ahead may be long, but with continued innovation and support, hydrogen could become a cornerstone of the global clean energy transition.

Whether you’re a driver, policymaker, or simply someone who cares about the planet, understanding hydrogen fuel cell vehicles is essential. They’re not just a niche technology—they’re a key piece of the puzzle in building a zero-emission world.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does a hydrogen fuel cell vehicle differ from a battery electric vehicle?

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles generate electricity onboard using hydrogen and oxygen, emitting only water vapor. Battery electric vehicles store electricity in large batteries and must be recharged from an external power source. FCEVs refuel faster and have longer range, while EVs are more energy-efficient.

Is hydrogen fuel safe for everyday use?

Yes, hydrogen is safe when handled properly. Modern FCEVs use high-strength tanks and multiple safety systems to prevent leaks. Hydrogen disperses quickly in air, reducing fire risk, and is rigorously tested to meet strict safety standards.

Where can I refuel a hydrogen car?

Hydrogen refueling stations are currently limited, with most located in California, Japan, South Korea, and parts of Europe. Expansion is underway, with plans to build hundreds more stations in the coming years.

How much does it cost to fuel a hydrogen car?

As of 2024, hydrogen costs about $12–$16 per kilogram in the U.S., with most cars using 0.8–1 kg per 60–70 miles. This makes fueling comparable to gasoline, though prices are expected to drop as production scales up.

Can hydrogen be produced sustainably?

Yes, green hydrogen made using renewable energy (like wind or solar) is completely sustainable. While most hydrogen today comes from natural gas, the shift to green hydrogen is accelerating globally.

Will hydrogen cars replace electric cars?

Not entirely. Battery EVs will likely dominate personal urban transport due to efficiency and infrastructure. Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are better suited for long-range, heavy-duty, and commercial applications where fast refueling and high energy density are critical.