Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) are emerging as a powerful alternative to traditional gas-powered cars and even battery-electric vehicles. With zero tailpipe emissions, quick refueling times, and long driving ranges, FCEVs could play a major role in decarbonizing transportation—especially for heavy-duty and long-haul applications.

Key Takeaways

- Zero Emissions at the Tailpipe: Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles only emit water vapor, making them a clean transportation option when powered by green hydrogen.

- Fast Refueling, Long Range: FCEVs can refuel in 3–5 minutes and travel 300–400 miles on a single tank—similar to gasoline vehicles.

- Ideal for Heavy-Duty Transport: Trucks, buses, and trains benefit most from hydrogen due to high energy density and reduced downtime.

- Green Hydrogen is Key: True environmental benefits depend on producing hydrogen using renewable energy sources like wind and solar.

- Infrastructure Challenges Remain: Limited hydrogen refueling stations and high production costs are current barriers to widespread adoption.

- Government Support is Growing: Countries like Japan, Germany, and the U.S. are investing heavily in hydrogen infrastructure and FCEV incentives.

- Future Mobility Ecosystem: Hydrogen could complement electric vehicles in a diversified, sustainable transportation model.

📑 Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Road to Cleaner Transportation

- How Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles Work

- Environmental Impact: Are FCEVs Truly Green?

- Current Market and Real-World Examples

- Challenges and Barriers to Adoption

- The Role of Government and Industry

- The Future of Transportation: A Multi-Technology Approach

- Conclusion: Driving Toward a Hydrogen-Powered Future

Introduction: The Road to Cleaner Transportation

Imagine a car that runs quietly, emits nothing but water vapor, and refuels in less time than it takes to grab a coffee. That’s not science fiction—it’s the promise of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs). As the world races to cut carbon emissions and combat climate change, transportation remains one of the biggest challenges. Cars, trucks, ships, and planes account for nearly a quarter of global CO₂ emissions. While electric vehicles (EVs) have made impressive strides, they’re not the only solution—especially when it comes to long-distance travel, heavy loads, or regions with limited charging infrastructure.

Enter hydrogen. This lightweight, abundant element has been used in industrial processes for decades, but only recently has it gained serious attention as a clean fuel for transportation. Unlike gasoline or diesel, hydrogen doesn’t burn. Instead, it powers vehicles through a chemical reaction in a fuel cell, producing electricity to drive the motor—and only water as a byproduct. This makes FCEVs a compelling option for a future where clean, efficient, and reliable transportation is non-negotiable.

How Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles Work

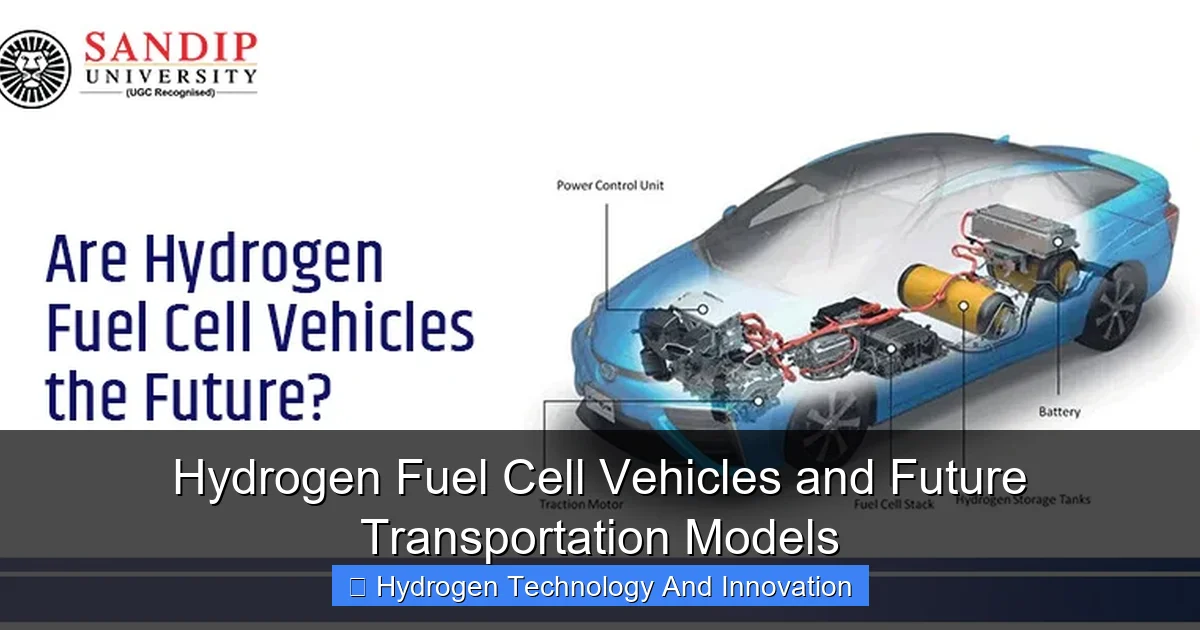

Visual guide about Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles and Future Transportation Models

Image source: facultyblog.sandipuniversity.edu.in

At first glance, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles might seem complex, but the core technology is surprisingly elegant. Let’s break it down in simple terms.

The Fuel Cell: Heart of the Vehicle

The fuel cell is where the magic happens. It’s a device that combines hydrogen gas from the onboard tank with oxygen from the air. This reaction produces electricity, water, and a bit of heat—no combustion, no smoke, no noise. The electricity generated powers the electric motor, just like in a battery-electric vehicle. But instead of storing energy in a large, heavy battery, FCEVs generate it on demand.

Most FCEVs use a type of fuel cell called a proton exchange membrane (PEM). These are compact, efficient, and work well at low temperatures—perfect for everyday driving. The hydrogen is stored in high-pressure tanks (usually around 700 bar), and the fuel cell stack converts it into usable power with impressive efficiency.

Refueling: Quick and Convenient

One of the biggest advantages of FCEVs over battery-electric vehicles is refueling time. While EVs can take 30 minutes to several hours to recharge—depending on the charger and battery size—hydrogen vehicles can be refilled in just 3 to 5 minutes. That’s about the same as filling up a gas tank. This makes FCEVs especially appealing for drivers who need to get back on the road quickly, like delivery trucks, taxis, or long-haul freight operators.

For example, the Toyota Mirai, one of the most well-known FCEVs, can travel up to 400 miles on a full tank and refuels in under five minutes. Compare that to a Tesla Model S, which might take 20–30 minutes at a Supercharger for an 80% charge—and even longer for a full tank. For commercial fleets or road-tripping families, that time difference adds up fast.

Energy Density: Why Hydrogen Wins for Heavy Loads

Another key benefit of hydrogen is its high energy density. By weight, hydrogen contains about three times more energy than gasoline. That means you need less of it to go the same distance—especially important for vehicles that carry heavy loads or travel long distances.

This is why hydrogen is being explored for applications where batteries fall short: freight trucks, city buses, trains, and even ships. A battery-electric semi-truck would need an enormous, heavy battery pack to match the range of a diesel truck, reducing cargo capacity and increasing costs. But a hydrogen-powered truck can carry more, go farther, and refuel quickly—making it a practical choice for logistics and public transit.

Environmental Impact: Are FCEVs Truly Green?

It’s easy to assume that because hydrogen vehicles emit only water, they’re automatically eco-friendly. But the real environmental impact depends on how the hydrogen is produced.

The Color Code of Hydrogen

Not all hydrogen is created equal. The industry uses a color-coded system to describe how it’s made:

- Grey hydrogen: Produced from natural gas through a process called steam methane reforming. This is the most common method today, but it releases CO₂—so it’s not truly clean.

- Blue hydrogen: Also made from natural gas, but the CO₂ emissions are captured and stored (carbon capture and storage, or CCS). It’s cleaner than grey, but still relies on fossil fuels.

- Green hydrogen: Produced using renewable energy (like wind or solar) to split water into hydrogen and oxygen via electrolysis. This method emits no greenhouse gases and is the gold standard for sustainable hydrogen.

For FCEVs to deliver on their environmental promise, they must run on green hydrogen. Otherwise, the benefits are significantly reduced. Fortunately, the shift is already underway. Countries like Germany, Australia, and Canada are investing heavily in green hydrogen production, and costs are expected to drop as technology improves and renewable energy becomes cheaper.

Lifecycle Emissions: A Fair Comparison

When comparing FCEVs to battery-electric vehicles (BEVs), it’s important to look at the full lifecycle—from production to disposal. While BEVs have zero tailpipe emissions, manufacturing their large lithium-ion batteries requires mining rare earth metals and significant energy. FCEVs, on the other hand, use smaller batteries and rely on platinum-based catalysts, which also have environmental costs.

However, studies show that over their lifetime, both FCEVs and BEVs produce far fewer emissions than gasoline cars—especially when powered by renewable energy. The exact advantage depends on the local electricity grid and hydrogen source. In regions with abundant solar or wind power, green hydrogen FCEVs can be among the cleanest options available.

Current Market and Real-World Examples

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are still a niche market, but they’re gaining momentum—especially in specific sectors.

Passenger Vehicles: Pioneers Leading the Way

Today, only a handful of FCEVs are available to consumers. The most notable include:

- Toyota Mirai: One of the first mass-produced FCEVs, the Mirai offers a sleek design, 400-mile range, and a smooth, quiet ride. Toyota has sold thousands worldwide, with strong adoption in California and Japan.

- Hyundai NEXO: Hyundai’s flagship hydrogen SUV boasts advanced safety features, a 414-mile range, and a futuristic interior. It’s available in select markets, including the U.S. and Europe.

- Honda Clarity Fuel Cell: Though discontinued in 2021, the Clarity was a popular lease-only model in California, praised for its comfort and efficiency.

These vehicles are often leased rather than sold outright, due to high upfront costs and limited refueling infrastructure. But for early adopters and fleet operators, they offer a glimpse into a cleaner driving future.

Commercial and Public Transit: Where Hydrogen Shines

While passenger FCEVs are still rare, hydrogen is making bigger waves in commercial transportation.

- Trucks: Companies like Hyundai, Nikola, and Toyota are developing hydrogen-powered semi-trucks. Hyundai’s XCIENT Fuel Cell trucks are already in operation in Switzerland and California, hauling goods across long distances with zero emissions.

- Buses: Cities like London, Berlin, and Tokyo are deploying hydrogen buses for public transit. These vehicles can carry dozens of passengers, refuel quickly, and operate all day without range anxiety.

- Trains: In Germany, hydrogen-powered trains (like the Coradia iLint by Alstom) are replacing diesel locomotives on non-electrified rail lines. They’re quieter, cleaner, and just as reliable.

- Shipping and Aviation: While still in early stages, companies like Airbus and Maersk are exploring hydrogen for future planes and cargo ships. These sectors are hard to electrify with batteries, making hydrogen a promising alternative.

These applications highlight a key trend: hydrogen isn’t trying to replace all EVs. Instead, it’s filling gaps where batteries struggle—long range, heavy loads, and fast turnaround times.

Challenges and Barriers to Adoption

Despite their potential, hydrogen fuel cell vehicles face several hurdles before they can go mainstream.

Limited Refueling Infrastructure

The biggest obstacle is infrastructure. As of 2024, there are fewer than 1,000 hydrogen refueling stations worldwide—most concentrated in California, Japan, and parts of Europe. Compare that to over 100,000 public EV charging stations in the U.S. alone. Without a reliable network, consumers and businesses can’t adopt FCEVs at scale.

Building hydrogen stations is expensive—each one can cost $1–2 million due to the need for high-pressure storage, safety systems, and specialized equipment. And because demand is still low, private companies are hesitant to invest without government support.

High Production and Distribution Costs

Green hydrogen is still more expensive to produce than grey or blue hydrogen. Electrolyzers (the machines that split water into hydrogen and oxygen) are costly, and renewable energy prices—while falling—still make green hydrogen 2–3 times pricier than fossil-based alternatives.

Transporting hydrogen is also tricky. It’s a tiny, leak-prone molecule that requires high-pressure tanks or cryogenic temperatures to store and move. Pipelines exist for industrial use, but building a new hydrogen grid would require massive investment.

Public Awareness and Perception

Many people still associate hydrogen with the Hindenburg disaster—a misconception that persists despite modern safety standards. In reality, hydrogen is no more dangerous than gasoline when handled properly. FCEVs undergo rigorous crash tests, and hydrogen tanks are designed to withstand extreme conditions.

Still, public education is needed. Consumers need to understand how FCEVs work, where they can refuel, and why they’re a smart choice for certain uses.

The Role of Government and Industry

The future of hydrogen transportation depends heavily on policy and investment.

Government Incentives and Policies

Countries around the world are launching hydrogen strategies to accelerate adoption:

- United States: The Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits for green hydrogen production, and the Department of Energy is funding hydrogen hubs across the country.

- European Union: The EU’s Hydrogen Strategy aims to install 40 GW of electrolyzers by 2030 and support FCEVs in transport.

- Japan and South Korea: Both nations are global leaders in hydrogen technology, with national roadmaps, subsidies, and public-private partnerships.

- China: Rapidly expanding hydrogen production and FCEV fleets, especially for buses and trucks.

These efforts are critical for scaling up production, lowering costs, and building infrastructure.

Industry Collaboration and Innovation

Automakers, energy companies, and tech firms are teaming up to advance hydrogen technology. Toyota and Shell, for example, have partnered to build hydrogen stations in California. Hyundai is working with logistics companies to deploy hydrogen trucks. And startups are developing more efficient electrolyzers and fuel cells.

Innovation is also happening in storage and distribution. Researchers are exploring liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs) and underground salt caverns for large-scale storage. These advancements could make hydrogen more practical and affordable in the coming years.

The Future of Transportation: A Multi-Technology Approach

It’s unlikely that hydrogen will replace all other forms of clean transportation. Instead, the future will likely be a mix of technologies, each suited to different needs.

Complementary, Not Competitive

Battery-electric vehicles are ideal for short- to medium-range trips, urban driving, and passenger cars. They’re already cost-competitive, widely available, and supported by growing charging networks.

Hydrogen, on the other hand, excels in long-haul freight, public transit, and industrial applications. It’s not about choosing one over the other—it’s about using the right tool for the job.

Think of it like this: EVs are the electric screwdriver—great for everyday tasks. Hydrogen is the power drill—needed for heavy-duty jobs. Both have a place in a modern, sustainable toolkit.

A Vision for 2030 and Beyond

By 2030, we could see:

- Thousands of hydrogen refueling stations across major economies.

- Hydrogen-powered trucks dominating freight corridors.

- City buses and delivery vans running on green hydrogen.

- Trains and ships using hydrogen to cut emissions.

- Green hydrogen production scaling up, driven by falling renewable energy costs.

This future isn’t guaranteed—it will require continued investment, innovation, and policy support. But the pieces are falling into place.

Conclusion: Driving Toward a Hydrogen-Powered Future

Hydrogen fuel cell vehicles are more than a futuristic concept—they’re a practical, clean solution for parts of the transportation sector that are hard to decarbonize. With zero emissions, fast refueling, and long range, FCEVs offer unique advantages that complement battery-electric vehicles. While challenges remain—especially in infrastructure and cost—the momentum is building.

The key to success lies in producing green hydrogen at scale and deploying it where it makes the most sense: heavy transport, public transit, and long-distance travel. With strong government support, industry collaboration, and public awareness, hydrogen could become a cornerstone of sustainable mobility.

The road ahead is long, but every mile driven by a hydrogen-powered vehicle is a step toward cleaner air, lower emissions, and a healthier planet. The future of transportation isn’t just electric—it’s diverse, smart, and powered by innovation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are hydrogen fuel cell vehicles safe?

Yes, FCEVs are designed with multiple safety features, including reinforced hydrogen tanks, leak detection systems, and automatic shut-off valves. They undergo rigorous testing and are considered as safe as conventional vehicles.

How far can a hydrogen car go on one tank?

Most hydrogen fuel cell vehicles can travel between 300 and 400 miles on a full tank—similar to gasoline-powered cars—making them ideal for long-distance travel.

Where can I refuel a hydrogen car?

Hydrogen refueling stations are currently limited, with most located in California, Japan, Germany, and parts of South Korea. Expansion is underway in the U.S., Europe, and China.

Is hydrogen more expensive than gasoline or electricity?

Currently, hydrogen fuel is more expensive per mile than gasoline or electricity, but costs are expected to fall as production scales up and green hydrogen becomes more common.

Can hydrogen be used in cold weather?

Yes, FCEVs perform well in cold climates. Unlike some battery-electric vehicles, hydrogen fuel cells don’t lose significant efficiency in low temperatures.

Will hydrogen replace electric vehicles?

No, hydrogen is unlikely to replace EVs. Instead, it will likely complement them—especially in heavy-duty and long-haul applications where batteries are less practical.