Hydrogen and electric vehicles represent two leading paths toward sustainable transportation, each with unique strengths and challenges. This article dives deep into their technological differences, from energy storage and refueling to environmental impact and real-world usability, helping you understand which might dominate the future of green mobility.

Key Takeaways

- Energy Source and Storage: Electric vehicles (EVs) store energy in lithium-ion batteries, while hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) generate electricity onboard using compressed hydrogen gas.

- Refueling Time: FCEVs can refuel in 3–5 minutes, similar to gasoline cars, whereas EVs typically take 30 minutes to several hours depending on charger type.

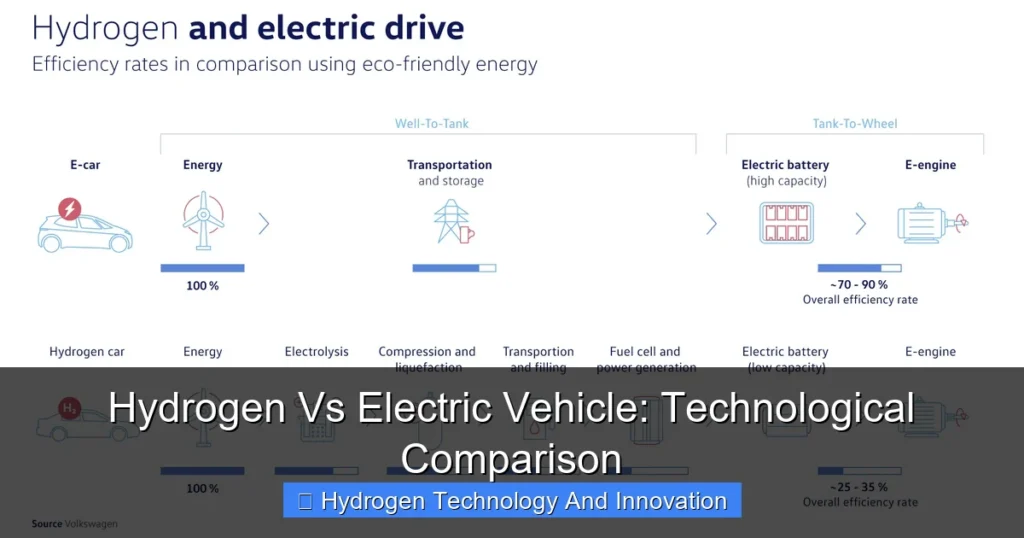

- Range and Efficiency: EVs are more energy-efficient (70–90% from grid to wheel), while FCEVs lose more energy in conversion (25–35% efficiency).

- Infrastructure Availability: EV charging stations are widespread and growing rapidly; hydrogen refueling stations are scarce, mostly limited to California and parts of Europe.

- Environmental Impact: Both produce zero tailpipe emissions, but the carbon footprint depends on how electricity or hydrogen is generated—renewables make both cleaner.

- Vehicle Cost and Maintenance: EVs are generally cheaper to buy and maintain; FCEVs have higher upfront costs and complex fuel cell systems requiring specialized servicing.

- Future Potential: EVs currently lead in adoption and innovation, but hydrogen may excel in heavy-duty transport like trucks, ships, and aviation.

📑 Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Green Mobility Revolution

- How They Work: The Core Technologies

- Energy Efficiency: From Source to Wheel

- Refueling and Charging: Convenience Matters

- Environmental Impact: Beyond Tailpipe Emissions

- Cost and Ownership: What’s the Real Price?

- Applications and Future Outlook

- Conclusion: Choosing the Right Path Forward

Introduction: The Green Mobility Revolution

The race to decarbonize transportation is heating up, and two technologies are at the forefront: electric vehicles (EVs) and hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs). As climate change accelerates and governments push for net-zero emissions, automakers and consumers alike are asking: which technology will power the cars of tomorrow? Both EVs and FCEVs offer zero tailpipe emissions, but they achieve this in fundamentally different ways. Understanding these differences is key to making informed decisions—whether you’re buying a car, investing in infrastructure, or shaping policy.

Electric vehicles have surged in popularity over the past decade. Companies like Tesla, Rivian, and legacy automakers such as Ford and GM have poured billions into EV development. Charging networks are expanding, battery prices are falling, and governments are offering incentives. Meanwhile, hydrogen vehicles remain a niche player, with only a handful of models available—like the Toyota Mirai and Hyundai NEXO—and limited refueling options. Yet, hydrogen holds promise, especially for applications where battery weight and charging time are deal-breakers.

How They Work: The Core Technologies

Visual guide about Hydrogen Vs Electric Vehicle: Technological Comparison

Image source: bacancysystems.com

At first glance, both EVs and FCEVs look like ordinary cars—but under the hood, their engineering tells a different story. Let’s break down how each system generates and uses energy.

Electric Vehicles: Batteries and Motors

Electric vehicles rely on rechargeable lithium-ion batteries to store electrical energy. When you plug in your EV, electricity from the grid (or a home solar system) charges these batteries. Once charged, the stored energy powers an electric motor, which turns the wheels. It’s a straightforward process: electricity in, motion out.

Modern EVs use advanced battery management systems to monitor temperature, voltage, and charge levels. This ensures safety and longevity. For example, Tesla’s 4680 battery cells offer higher energy density and faster charging, while companies like CATL are developing sodium-ion batteries as a cheaper, more sustainable alternative to lithium.

One major advantage of EVs is regenerative braking. When you slow down, the motor acts as a generator, converting kinetic energy back into electricity and feeding it into the battery. This improves efficiency and extends range.

Hydrogen Fuel Cell Vehicles: Chemistry in Motion

Hydrogen vehicles take a different approach. Instead of storing electricity, they carry compressed hydrogen gas in high-pressure tanks. Inside the vehicle, a fuel cell stack combines hydrogen with oxygen from the air in a chemical reaction that produces electricity, water, and heat. This electricity then powers an electric motor—just like in an EV.

The byproduct? Pure water vapor—nothing more. That’s why FCEVs are often called “zero-emission” vehicles. But here’s the catch: the hydrogen must be produced, compressed, transported, and stored—all of which consume energy.

Fuel cells use a catalyst—usually platinum—to split hydrogen into protons and electrons. The protons pass through a membrane, while the electrons create an electric current. This process is clean and quiet, but it’s also complex and expensive. The fuel cell stack is sensitive to temperature and humidity, and it requires precise control systems to operate efficiently.

Energy Efficiency: From Source to Wheel

When comparing green technologies, efficiency is king. How much of the original energy actually makes it to the wheels? Let’s follow the energy journey for both EVs and FCEVs.

EV Efficiency: The Clear Winner

Electric vehicles are remarkably efficient. According to the U.S. Department of Energy, EVs convert about 77% of the electrical energy from the grid to power at the wheels. Even when accounting for charging losses and battery inefficiencies, the overall efficiency ranges from 70% to 90%.

This high efficiency comes from the simplicity of the system. There are fewer energy conversions: electricity goes into the battery, then directly to the motor. No combustion, no heat waste, no mechanical losses from gears and transmissions.

For example, a Tesla Model 3 uses about 25 kWh of electricity to travel 100 miles. If charged from a clean grid (like one powered by wind or solar), its carbon footprint is minimal. Even on a coal-heavy grid, EVs still outperform gasoline cars in lifecycle emissions.

Hydrogen Efficiency: A Longer Chain

Hydrogen vehicles face a longer and less efficient energy chain. First, hydrogen must be produced—usually via electrolysis (splitting water using electricity) or steam methane reforming (using natural gas). Electrolysis is clean but energy-intensive; reforming is cheaper but emits CO₂.

Next, the hydrogen must be compressed to 700 times atmospheric pressure and cooled for storage. This process consumes significant energy. Then, it’s transported—often by truck—to refueling stations, which adds more energy loss.

Finally, inside the vehicle, the fuel cell converts hydrogen to electricity at about 60% efficiency. But when you factor in production, compression, transport, and conversion, the total well-to-wheel efficiency drops to just 25% to 35%.

In practical terms, it takes about three times more energy to power a hydrogen car the same distance as an EV. That’s a major drawback, especially as we strive to maximize renewable energy use.

Refueling and Charging: Convenience Matters

One of the biggest concerns for drivers is how easy it is to “fill up.” Range anxiety and downtime can make or break a technology’s adoption.

EV Charging: Speed and Infrastructure

Charging an EV depends on the type of charger:

– Level 1 (120V): Plugs into a standard outlet. Adds about 4–5 miles of range per hour. Best for overnight charging at home.

– Level 2 (240V): Common in homes, workplaces, and public stations. Adds 25–30 miles per hour. Most EVs can go from 20% to 80% in 4–8 hours.

– DC Fast Charging (Level 3): Found along highways. Can charge a battery to 80% in 20–40 minutes. Tesla Superchargers and Electrify America stations are leading the way.

The good news? EV charging infrastructure is growing fast. In the U.S., there are over 160,000 public charging ports, and companies like ChargePoint and EVgo are expanding networks. Home charging is convenient—just plug in when you get home, like a smartphone.

But challenges remain. Fast chargers aren’t available everywhere, and charging times can vary. Cold weather reduces battery efficiency, and long road trips require planning. Still, for most daily driving, EVs are more than capable.

Hydrogen Refueling: Fast but Rare

Here’s where hydrogen shines: refueling time. A hydrogen car can be filled in 3–5 minutes—just like a gasoline vehicle. That’s a huge advantage for long-haul trucking, taxis, or fleet vehicles that can’t afford downtime.

However, the infrastructure is almost nonexistent outside a few regions. As of 2024, the U.S. has fewer than 100 hydrogen refueling stations, almost all in California. Europe and Japan have more, but still far fewer than EV chargers.

Building hydrogen stations is expensive—each can cost $1–2 million. They require high-pressure storage, safety systems, and a reliable hydrogen supply. Plus, hydrogen is tricky to transport. It’s the smallest molecule, so it leaks easily and requires specialized pipelines or trucks.

For now, hydrogen refueling is only practical in limited areas. But if infrastructure scales, it could become a game-changer for certain applications.

Environmental Impact: Beyond Tailpipe Emissions

Both EVs and FCEVs produce zero emissions while driving. But the real environmental impact depends on how the energy is made.

EVs: Cleaner with Renewables

The carbon footprint of an EV depends on the electricity grid. In regions with lots of coal, EVs still emit CO₂—but less than gasoline cars. In places with clean energy (like Norway or Iceland), EVs are nearly carbon-free.

Battery production is another concern. Mining lithium, cobalt, and nickel has environmental and ethical issues. However, recycling programs and new battery chemistries (like lithium-iron-phosphate) are reducing these impacts.

Over time, as grids get greener and batteries last longer, EVs will become even cleaner. Studies show that over a 150,000-mile lifespan, an EV emits 50–70% less CO₂ than a gasoline car, even when accounting for manufacturing.

Hydrogen: The Green Hydrogen Question

Hydrogen’s environmental impact hinges on how it’s produced:

– Grey hydrogen: Made from natural gas via steam reforming. Emits CO₂—about 9–12 kg per kg of hydrogen. Not sustainable.

– Blue hydrogen: Same process, but CO₂ is captured and stored. Better, but still relies on fossil fuels.

– Green hydrogen: Made by electrolysis using renewable electricity. Zero emissions—but expensive and energy-intensive.

Currently, over 95% of hydrogen is grey or blue. Green hydrogen is growing, but it’s still a small fraction. Until green hydrogen becomes mainstream, FCEVs may not be as clean as they seem.

Moreover, hydrogen production uses a lot of water—about 9 liters per kg of hydrogen. In water-scarce regions, this could be a concern.

Cost and Ownership: What’s the Real Price?

Let’s talk money. Which technology offers better value for drivers and fleets?

Upfront and Operating Costs

EVs have higher upfront costs than gasoline cars, but prices are falling. The average EV now costs around $50,000, though models like the Chevrolet Bolt and Tesla Model 3 start under $40,000. Federal and state incentives can reduce this further.

Operating costs are low. Electricity is cheaper than gasoline—about $1 per gallon equivalent. Maintenance is simpler: no oil changes, fewer moving parts, and regenerative braking reduces wear on pads.

Hydrogen vehicles are much more expensive. The Toyota Mirai starts at around $50,000, and the Hyundai NEXO is similar. But hydrogen fuel costs about $16 per kg—and a Mirai gets about 67 miles per kg. That’s roughly $0.24 per mile, compared to $0.04–$0.06 for an EV.

Plus, hydrogen stations often offer free fuel for early adopters, but that won’t last. And maintenance is more complex—fuel cells degrade over time and may need replacement after 100,000–150,000 miles.

Resale Value and Market Trends

EVs are gaining resale value as demand grows. Tesla models, in particular, hold their value well. But battery degradation can be a concern—though modern EVs are designed to last 200,000+ miles with minimal capacity loss.

Hydrogen vehicles have poor resale value due to limited demand and infrastructure. Few buyers are willing to take the risk. This could change if hydrogen becomes mainstream, but for now, it’s a barrier.

Applications and Future Outlook

So, which technology wins? The answer isn’t black and white—it depends on the use case.

Where EVs Excel

Electric vehicles are ideal for:

– Personal cars: Daily commuting, city driving, short trips.

– Urban fleets: Delivery vans, taxis, ride-sharing.

– Home and workplace charging: Easy to integrate with solar panels and smart grids.

With rapid advancements in battery tech, charging speed, and autonomous driving, EVs are poised to dominate passenger transportation.

Where Hydrogen Shines

Hydrogen has potential in areas where batteries fall short:

– Long-haul trucking: Heavy loads, long distances, fast refueling.

– Aviation and shipping: High energy density needed; batteries are too heavy.

– Industrial use: Steel production, chemical manufacturing, backup power.

Companies like Nikola and Toyota are developing hydrogen trucks. Airbus is working on hydrogen-powered planes. These applications could drive demand for green hydrogen and justify infrastructure investment.

The Future: Coexistence, Not Competition

Rather than one technology replacing the other, the future may involve coexistence. EVs will likely dominate passenger vehicles, while hydrogen powers heavy transport and industrial sectors.

Governments and companies are investing in both. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act supports EV manufacturing and hydrogen hubs. The European Union has a Hydrogen Strategy. Japan and South Korea are betting big on fuel cells.

Innovation will continue. Solid-state batteries could make EVs even more efficient. Green hydrogen costs may fall with scaling and renewable energy growth. The key is to deploy the right technology in the right place.

Conclusion: Choosing the Right Path Forward

The hydrogen vs electric vehicle debate isn’t about picking a winner—it’s about understanding strengths, limitations, and real-world needs. Electric vehicles are efficient, increasingly affordable, and supported by growing infrastructure. They’re perfect for most drivers today.

Hydrogen vehicles offer fast refueling and high energy density, making them promising for heavy-duty and long-range applications. But they face steep challenges: low efficiency, high costs, and limited infrastructure.

As we transition to a clean energy future, both technologies have roles to play. The goal isn’t to choose one over the other, but to build a diversified, sustainable transportation system. Whether you’re buying a car, investing in energy, or shaping policy, the key is to stay informed and flexible. The road ahead is electric—and maybe a little bit hydrogen too.

Frequently Asked Questions

Which is more efficient: hydrogen or electric vehicles?

Electric vehicles are significantly more efficient, converting 70–90% of energy from source to wheel, while hydrogen vehicles achieve only 25–35% due to energy losses in production, compression, and conversion.

How long does it take to refuel a hydrogen car?

Hydrogen vehicles can be refueled in 3–5 minutes, similar to gasoline cars, making them much faster than most EV charging options.

Are hydrogen vehicles really zero-emission?

While they emit only water vapor from the tailpipe, the overall emissions depend on how the hydrogen is produced. Green hydrogen (from renewables) is clean, but most hydrogen today is made from fossil fuels.

Why aren’t there more hydrogen refueling stations?

Hydrogen stations are expensive to build and require specialized infrastructure. Currently, they’re only viable in limited regions like California and parts of Europe and Japan.

Can hydrogen be used in passenger cars?

Yes, models like the Toyota Mirai and Hyundai NEXO are available, but high costs, limited range, and lack of infrastructure make them less practical than EVs for most drivers.

Will hydrogen replace electric vehicles?

Unlikely. EVs are better suited for personal transportation, while hydrogen may complement them in heavy-duty sectors like trucking, shipping, and aviation.