Hydrogen fuel cell technology offers clean energy potential but comes with notable risks. From flammability and storage issues to high costs and infrastructure gaps, understanding these challenges is key to safer, smarter adoption.

Key Takeaways

- Safety concerns exist due to hydrogen’s high flammability and low ignition energy. Proper handling, storage, and detection systems are essential to prevent leaks and explosions.

- Hydrogen storage is complex and energy-intensive. Compressing or liquefying hydrogen requires significant energy and specialized tanks, increasing costs and risks.

- Infrastructure for hydrogen distribution is underdeveloped. Limited refueling stations and transport networks hinder widespread adoption, especially compared to electric vehicles.

- Production methods often rely on fossil fuels. Most hydrogen today comes from natural gas, which undermines its environmental benefits unless green hydrogen scales up.

- High costs remain a major barrier. Fuel cells, storage systems, and infrastructure require expensive materials like platinum, keeping prices high.

- Durability and performance can degrade over time. Fuel cells face challenges from contamination, temperature extremes, and mechanical stress.

- Regulatory and standardization gaps persist. Inconsistent safety codes and lack of global standards slow innovation and public trust.

📑 Table of Contents

- Introduction: The Promise and Peril of Hydrogen Fuel Cells

- Safety Risks: Flammability, Leaks, and Explosion Hazards

- Storage and Transportation Challenges

- Infrastructure Gaps: The Chicken-and-Egg Problem

- Environmental and Production Concerns

- Economic and Material Challenges

- Durability, Performance, and Reliability Issues

- Regulatory and Standardization Gaps

- Conclusion: Balancing Risk and Reward

Introduction: The Promise and Peril of Hydrogen Fuel Cells

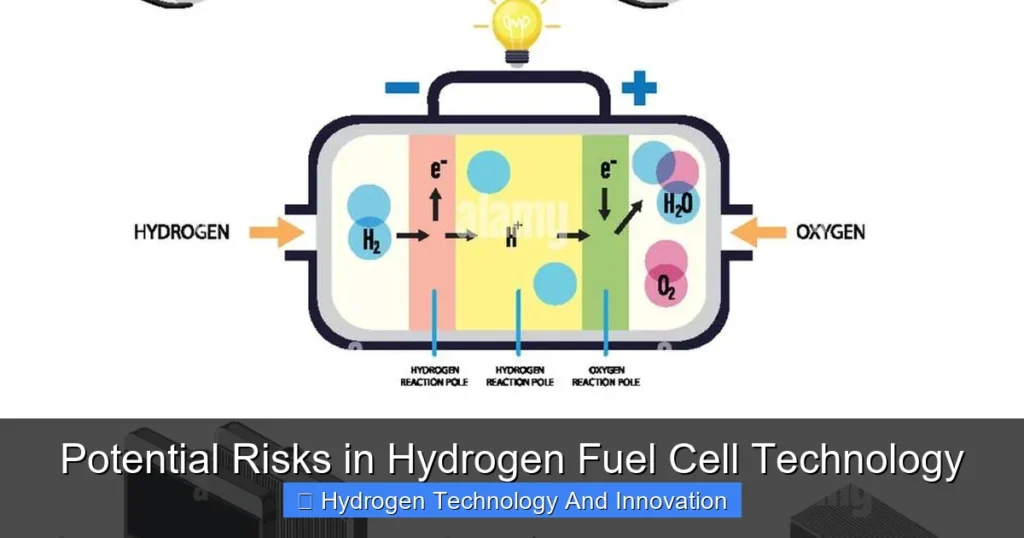

Hydrogen fuel cell technology has long been hailed as a game-changer in the clean energy revolution. Imagine vehicles that emit only water vapor, industrial processes powered without carbon emissions, and energy systems that store renewable power efficiently. That’s the vision fuel cells promise. They convert hydrogen and oxygen into electricity through an electrochemical reaction, producing zero greenhouse gases at the point of use. From cars and buses to backup power systems and even spacecraft, hydrogen fuel cells are being tested and deployed across industries.

But like any emerging technology, hydrogen fuel cells come with their share of challenges. While the benefits are compelling, the risks involved can’t be ignored. These aren’t just technical hurdles—they’re real-world concerns that affect safety, cost, scalability, and public acceptance. As governments and companies invest billions into hydrogen infrastructure, it’s crucial to understand not just the potential, but the pitfalls. After all, a technology that’s too risky or too expensive won’t gain public trust, no matter how clean it is.

Safety Risks: Flammability, Leaks, and Explosion Hazards

Visual guide about Potential Risks in Hydrogen Fuel Cell Technology

Image source: aeologic.com

One of the most pressing concerns with hydrogen fuel cell technology is safety. Hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant element in the universe, but that also makes it tricky to handle. It’s highly flammable, with a wide flammability range—meaning it can ignite at concentrations as low as 4% in air. Compare that to gasoline, which requires a much narrower range to burn. Hydrogen also has a low ignition energy; even a small spark from static electricity can trigger combustion.

Hydrogen’s Unique Combustion Properties

Unlike gasoline or natural gas, hydrogen burns with a nearly invisible flame. This makes leaks or fires hard to detect with the naked eye, especially in daylight. In enclosed spaces like garages or tunnels, a small leak can quickly accumulate and create an explosive atmosphere. While hydrogen disperses rapidly into the air due to its low density, this only helps in open environments. Indoors or in poorly ventilated areas, the risk increases significantly.

There have been real-world incidents that highlight these dangers. In 2019, a hydrogen explosion at a fueling station in Norway injured two people and damaged nearby vehicles. The cause? A faulty valve led to a hydrogen leak that ignited. While no fatalities occurred, the event raised alarms about the safety of hydrogen infrastructure. Similarly, in 2021, a hydrogen leak at a research facility in South Korea caused a fire, underscoring the need for rigorous safety protocols.

Mitigation Strategies and Safety Systems

So, how do we manage these risks? The answer lies in engineering controls, detection systems, and strict operational procedures. Modern hydrogen systems are equipped with multiple layers of protection. For example, hydrogen sensors are installed in storage areas, fueling stations, and vehicles to detect leaks early. These sensors can trigger alarms, shut off valves, or activate ventilation systems automatically.

Materials used in hydrogen systems are also carefully selected. Tanks and pipelines must withstand high pressures and resist hydrogen embrittlement—a phenomenon where hydrogen atoms penetrate metal, making it brittle and prone to cracking. Composite materials, such as carbon fiber-reinforced tanks, are now standard in fuel cell vehicles because they’re both strong and lightweight.

Another key strategy is ventilation. Hydrogen fueling stations and maintenance facilities are designed with open layouts and high ceilings to allow any leaked gas to rise and disperse quickly. In vehicles, hydrogen tanks are often placed in protected areas, like under the floor or behind reinforced panels, to minimize damage in a crash.

Despite these safeguards, human error remains a factor. Training for technicians, emergency responders, and operators is essential. Firefighters, for instance, need special training to handle hydrogen fires, which require different tactics than gasoline fires. Instead of smothering the flame, they often let it burn out safely while cooling surrounding structures.

Storage and Transportation Challenges

Storing and transporting hydrogen is one of the biggest technical hurdles in fuel cell technology. Unlike gasoline or diesel, hydrogen can’t be stored in simple tanks at ambient conditions. It’s a gas at room temperature and pressure, and to store enough of it for practical use—like powering a car for 300 miles—you need to compress it or turn it into a liquid.

Compression and Liquefaction: Energy-Intensive Processes

Compressed hydrogen gas (CGH2) is the most common method for vehicle fueling. Tanks are pressurized to 350 or 700 bar (5,000 to 10,000 psi)—that’s over 300 times atmospheric pressure. While this allows for reasonable range, the compression process itself consumes a lot of energy. Compressing hydrogen to 700 bar can use up to 10–15% of the energy content of the hydrogen itself. That’s a significant efficiency loss.

Liquefied hydrogen (LH2) offers higher energy density, but it comes with its own challenges. To liquefy hydrogen, it must be cooled to -253°C (-423°F)—colder than liquid nitrogen. This requires massive refrigeration systems and highly insulated tanks, similar to those used for liquid natural gas (LNG). The energy cost is even higher: liquefaction can consume 30% or more of the hydrogen’s energy content.

Both methods require specialized infrastructure. High-pressure compressors, cryogenic pumps, and vacuum-insulated storage tanks are expensive and complex to maintain. For example, Toyota’s Mirai and Hyundai’s NEXO use compressed hydrogen tanks, but they require regular inspections and certifications to ensure safety. Any failure in the tank or valve system could lead to rapid depressurization or rupture.

Transportation: Pipelines, Trucks, and Future Solutions

Transporting hydrogen from production sites to fueling stations is another bottleneck. Currently, most hydrogen is moved by truck—either as compressed gas in tube trailers or as liquid in cryogenic tankers. This method is costly, inefficient, and limited in range. A single truck can carry only a few hundred kilograms of hydrogen, enough to fuel a handful of vehicles.

Pipelines offer a more scalable solution, but the existing natural gas pipeline network isn’t fully compatible with hydrogen. Hydrogen can cause embrittlement in steel pipes and increase leakage rates through seals and joints. Retrofitting pipelines or building new hydrogen-specific ones is expensive and time-consuming. Countries like Germany and the Netherlands are piloting hydrogen pipeline projects, but widespread adoption is still years away.

Emerging technologies aim to solve these issues. One promising approach is chemical hydrogen storage, where hydrogen is bound to a carrier like ammonia or liquid organic hydrogen carriers (LOHCs). These substances are easier to transport and store, and hydrogen can be released on demand. However, the release process often requires heat or catalysts, adding complexity.

Another idea is on-site hydrogen production using electrolysis powered by renewable energy. This eliminates the need for long-distance transport but requires space, water, and reliable electricity. While feasible for large industrial users, it’s less practical for small fueling stations or rural areas.

Infrastructure Gaps: The Chicken-and-Egg Problem

Even if hydrogen fuel cells are safe and efficient, they can’t succeed without infrastructure. Right now, the lack of refueling stations is a major barrier. In the U.S., there are fewer than 100 public hydrogen fueling stations, mostly in California. Compare that to over 150,000 gas stations or 50,000 electric vehicle chargers. This scarcity makes it hard for consumers to adopt hydrogen vehicles, even if they want to.

Limited Refueling Networks

The infrastructure gap creates a classic chicken-and-egg problem. Automakers are hesitant to mass-produce hydrogen vehicles because there aren’t enough fueling stations. Meanwhile, energy companies are reluctant to build stations because there aren’t enough vehicles to justify the investment. This cycle slows adoption and keeps costs high.

California is the exception, with state incentives and partnerships between automakers, energy firms, and government agencies. The California Fuel Cell Partnership has helped deploy over 60 hydrogen stations and hundreds of fuel cell vehicles. But even there, the network is patchy. Drivers often face long drives between stations, and some stations experience downtime due to maintenance or supply issues.

In Europe, countries like Germany, France, and the Netherlands are investing in hydrogen corridors—routes with multiple fueling stations for trucks and buses. Japan and South Korea are also pushing hydrogen as part of their national energy strategies. But globally, progress is uneven. Developing countries often lack the capital and regulatory frameworks to support hydrogen infrastructure.

Cost of Building and Maintaining Stations

Building a hydrogen fueling station isn’t cheap. A single station can cost between $1 million and $3 million, depending on size and technology. That’s significantly more than a fast-charging EV station, which might cost $100,000 to $500,000. The high cost comes from specialized equipment: compressors, storage tanks, dispensers, and safety systems.

Maintenance is another expense. Hydrogen systems require regular inspections, leak testing, and component replacements. Technicians need specialized training, and spare parts may be hard to source. In remote areas, the lack of skilled labor can lead to prolonged downtime.

To make matters worse, hydrogen stations often operate at a loss. With low vehicle adoption, they can’t generate enough revenue to cover costs. Some stations rely on government subsidies or corporate partnerships to stay open. Without long-term funding, many may shut down, further discouraging investment.

Environmental and Production Concerns

One of the biggest ironies of hydrogen fuel cell technology is that most hydrogen today isn’t green. Despite its clean-burning reputation, over 95% of hydrogen is produced from fossil fuels—primarily through steam methane reforming (SMR) of natural gas. This process releases carbon dioxide, undermining the environmental benefits of fuel cells.

Grey, Blue, and Green Hydrogen: What’s the Difference?

Hydrogen is often categorized by color based on its production method:

– Grey hydrogen is made from natural gas without capturing emissions. It’s the most common and cheapest form but has a high carbon footprint.

– Blue hydrogen also uses natural gas, but the CO2 is captured and stored (carbon capture and storage, or CCS). It’s cleaner than grey but still relies on fossil fuels and isn’t emission-free.

– Green hydrogen is produced using renewable electricity to split water into hydrogen and oxygen via electrolysis. It’s the only truly sustainable option, but it’s currently expensive and energy-intensive.

Right now, green hydrogen makes up less than 1% of global production. The main barrier is cost. Electrolyzers are expensive, and renewable electricity must be abundant and cheap. In regions with high solar or wind potential, like Australia or Chile, green hydrogen is becoming more viable. But in most places, it’s still not competitive with grey hydrogen.

The Lifecycle Emissions Question

Even if a hydrogen vehicle emits only water, the full lifecycle emissions matter. If the hydrogen comes from natural gas, the overall carbon footprint can be similar to or worse than gasoline vehicles. A 2021 study by Cornell and Stanford researchers found that blue hydrogen could have a higher greenhouse gas footprint than burning natural gas directly, due to methane leaks and energy use in CCS.

This doesn’t mean hydrogen is inherently bad—it means we need to be honest about how it’s made. For fuel cells to be truly sustainable, the entire supply chain must shift to renewables. That includes not just production, but also electricity for compression, liquefaction, and transportation.

Economic and Material Challenges

Cost is a major obstacle to hydrogen fuel cell adoption. From the fuel cells themselves to the infrastructure, everything is expensive. A single fuel cell stack for a car can cost thousands of dollars, largely due to the use of platinum as a catalyst. Platinum is rare, costly, and subject to supply chain risks.

High Material and Manufacturing Costs

Platinum is essential for the electrochemical reaction in proton exchange membrane (PEM) fuel cells, the most common type used in vehicles. While researchers are working on reducing or replacing platinum with cheaper alternatives like iron-nitrogen-carbon catalysts, these are not yet ready for mass production.

Other components, such as membranes, gas diffusion layers, and bipolar plates, also require precision manufacturing. The production process is complex and not easily scalable. Unlike lithium-ion batteries, which have benefited from economies of scale in the EV industry, fuel cells haven’t seen the same level of mass production.

Lack of Economies of Scale

Because demand is low, manufacturers can’t spread fixed costs over large volumes. This keeps prices high. For example, the Toyota Mirai starts at around $50,000, and hydrogen fuel costs about $16 per kilogram—equivalent to $4–5 per gallon of gasoline. While some states offer rebates, the total cost of ownership remains higher than for battery electric vehicles.

Until production scales up, costs will stay high. But scaling requires demand, which depends on infrastructure, policy support, and consumer confidence—creating another chicken-and-egg dilemma.

Durability, Performance, and Reliability Issues

Fuel cells aren’t just expensive—they can also degrade over time. Unlike batteries, which store energy, fuel cells generate it through a continuous chemical reaction. This process puts stress on materials, leading to wear and performance loss.

Contamination and Degradation

Fuel cells are sensitive to impurities. Even small amounts of carbon monoxide, sulfur, or ammonia in the hydrogen supply can poison the catalyst, reducing efficiency. Air pollutants can also affect the cathode side of the cell. Over time, this leads to voltage decay and shorter lifespan.

Temperature extremes are another issue. Fuel cells work best at moderate temperatures (60–80°C). In cold climates, startup can be slow, and water management becomes tricky—ice can block gas flow. In hot environments, cooling systems must work harder, increasing energy use.

Mechanical stress from vibration, pressure cycles, and thermal expansion can also damage components. In vehicles, this is especially concerning. A fuel cell in a car experiences constant movement, temperature changes, and potential impacts. Ensuring long-term reliability requires robust design and rigorous testing.

Real-World Performance Gaps

In ideal lab conditions, fuel cells can last 5,000 to 10,000 hours. But in real-world applications, lifespan is often shorter. For example, fuel cell buses in transit fleets have shown degradation after just a few years of service. Maintenance, fuel quality, and operating conditions all play a role.

Improving durability is a key focus for researchers. Advances in materials science, better water and thermal management, and improved system controls are helping. But until fuel cells can match the reliability of internal combustion engines or batteries, widespread adoption will remain a challenge.

Regulatory and Standardization Gaps

Finally, the lack of consistent regulations and standards slows progress. Safety codes for hydrogen vary by country and even by state. In the U.S., regulations are set by agencies like OSHA, NFPA, and DOT, but they’re not always aligned. In Europe, the EU has harmonized some standards, but implementation differs across member states.

Need for Global Standards

Without common standards, manufacturers face uncertainty. A fuel cell vehicle approved in Japan may not meet U.S. safety requirements. This complicates global trade and increases development costs.

Efforts are underway to create international standards through organizations like ISO and IEC. For example, ISO/TS 19887 covers safety for hydrogen fueling stations. But adoption is voluntary, and enforcement is inconsistent.

Stronger, globally recognized standards would boost confidence, reduce costs, and accelerate innovation. They would also help emergency responders, insurers, and regulators understand and manage the risks.

Conclusion: Balancing Risk and Reward

Hydrogen fuel cell technology holds immense promise. It could decarbonize transportation, industry, and energy storage in ways that batteries alone cannot. But the risks—safety, storage, infrastructure, cost, and sustainability—are real and must be addressed.

The path forward requires a balanced approach. We need continued investment in research, stronger safety protocols, supportive policies, and public education. Green hydrogen must become the norm, not the exception. Infrastructure must expand beyond niche markets. And costs must come down through innovation and scale.

With careful planning and collaboration, the risks can be managed. Hydrogen won’t replace all other clean technologies, but it can play a vital role in a diversified energy future. The key is to move forward with eyes wide open—embracing the potential while respecting the pitfalls.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is hydrogen fuel cell technology safe?

Yes, when proper safety measures are in place. Hydrogen is flammable, but modern systems include leak detection, ventilation, and robust materials to minimize risks. Incidents are rare and often result from human error or equipment failure.

Why is hydrogen storage so difficult?

Hydrogen has low energy density by volume, so it must be compressed or liquefied to store enough for practical use. Both methods require high energy input and specialized, expensive equipment.

Can hydrogen be produced without fossil fuels?

Yes, through electrolysis powered by renewable energy, known as green hydrogen. However, it’s currently more expensive than fossil-based methods and makes up a small fraction of global production.

Why aren’t there more hydrogen fueling stations?

High construction costs, low vehicle adoption, and lack of investment create a chicken-and-egg problem. Building stations is risky without demand, and demand won’t grow without infrastructure.

Are hydrogen vehicles more expensive than electric ones?

Generally, yes. Fuel cell vehicles cost more upfront, and hydrogen fuel is pricier per mile than electricity. However, they offer faster refueling and longer range in some cases.

Will hydrogen replace batteries in clean transportation?

Unlikely. Batteries are better for short-range vehicles, while hydrogen may excel in heavy transport like trucks and ships. Both technologies will likely coexist in a clean energy future.