Hydrogen fuel cells generate clean electricity by combining hydrogen and oxygen, producing only water and heat as byproducts. This article breaks down the chemistry behind fuel cells, their types, efficiency, and why they’re a game-changer for sustainable energy.

Key Takeaways

- Hydrogen fuel cells produce electricity through an electrochemical reaction, not combustion. This makes them highly efficient and emission-free at the point of use.

- The core chemistry involves splitting hydrogen into protons and electrons at the anode, then recombining them with oxygen at the cathode. This process generates a flow of electrons—electricity—while producing only water.

- Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) fuel cells are the most common type for vehicles and portable applications. They operate at low temperatures and respond quickly to power demands.

- Fuel cells are more efficient than internal combustion engines, converting up to 60% of hydrogen’s energy into electricity. Combined with waste heat recovery, efficiency can exceed 80%.

- Hydrogen must be produced sustainably—via electrolysis using renewable energy—to be truly green. Current production often relies on fossil fuels, which limits environmental benefits.

- Challenges include hydrogen storage, infrastructure, and cost, but innovation is rapidly advancing. New materials and scaling are making fuel cells more viable every year.

- Applications range from cars and buses to backup power systems and even spacecraft. The versatility of fuel cells makes them a key player in the clean energy transition.

📑 Table of Contents

Introduction: Powering the Future with Hydrogen

Imagine a car that emits nothing but water vapor, a backup generator that runs silently during a blackout, or a spacecraft powered by clean, efficient energy. These aren’t scenes from a sci-fi movie—they’re real-world applications of hydrogen fuel cells. At the heart of this technology is a simple yet powerful chemical process that turns hydrogen and oxygen into electricity, heat, and water. No smoke, no fumes, no carbon emissions. Just clean energy.

Hydrogen fuel cells are often called the “holy grail” of clean energy because they offer a way to generate power without burning fossil fuels. Unlike batteries, which store energy, fuel cells produce electricity continuously as long as they’re supplied with fuel—in this case, hydrogen and oxygen. This makes them ideal for applications where long runtimes and quick refueling are essential, such as in heavy-duty trucks, buses, and industrial equipment.

But how exactly does this magic happen? What’s going on inside a fuel cell that turns gas into usable electricity? The answer lies in electrochemistry—the science of chemical reactions that produce electricity. In this article, we’ll dive deep into the chemistry of hydrogen fuel cells, explain how they work step by step, explore different types, and discuss their real-world uses and challenges. Whether you’re a student, a tech enthusiast, or just curious about clean energy, this guide will make the science clear and accessible.

What Is a Hydrogen Fuel Cell?

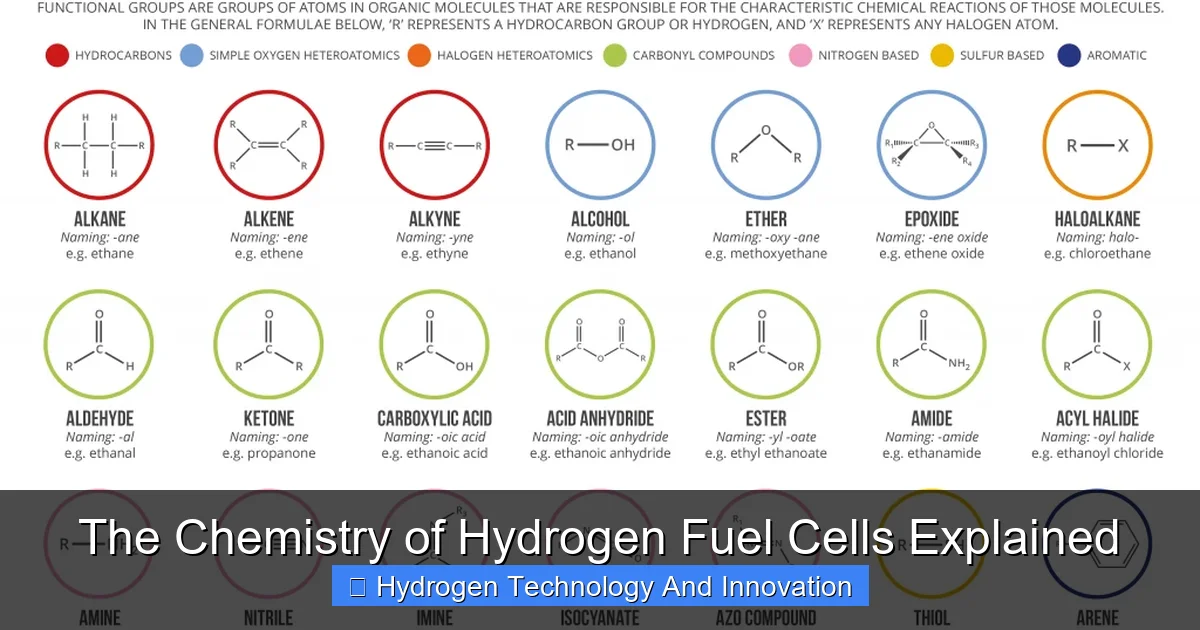

Visual guide about The Chemistry of Hydrogen Fuel Cells Explained

Image source: compoundchem.com

At its core, a hydrogen fuel cell is an electrochemical device that converts the chemical energy of hydrogen and oxygen into electrical energy. Think of it like a battery that never runs out—as long as you keep feeding it fuel. But unlike a battery, which stores energy in chemicals and eventually needs recharging, a fuel cell generates power through a continuous reaction.

The basic structure of a fuel cell includes three main parts: an anode (negative electrode), a cathode (positive electrode), and an electrolyte in between. The electrolyte is a special material that allows ions to pass through but blocks electrons. This separation forces electrons to take a different path—through an external circuit—creating an electric current that can power devices.

Hydrogen gas (H₂) is fed into the anode side of the fuel cell. There, a catalyst—usually platinum—splits each hydrogen molecule into two protons (H⁺) and two electrons (e⁻). The protons travel through the electrolyte to the cathode, while the electrons are forced to flow through an external wire, generating electricity. On the cathode side, oxygen (usually from air) combines with the incoming protons and electrons to form water (H₂O). That’s it. No combustion. No pollution. Just clean, quiet power.

How Does the Reaction Work?

Let’s break down the chemical reactions step by step. At the anode, hydrogen molecules are split:

Anode Reaction:

2H₂ → 4H⁺ + 4e⁻

This means two hydrogen molecules lose their electrons and become four positively charged protons. The electrons are released into the external circuit, creating an electric current.

At the cathode, oxygen from the air reacts with the protons and electrons to form water:

Cathode Reaction:

O₂ + 4H⁺ + 4e⁻ → 2H₂O

So, one oxygen molecule combines with four protons and four electrons to produce two water molecules. The overall reaction is:

Overall Reaction:

2H₂ + O₂ → 2H₂O + electricity + heat

This reaction is the reverse of water electrolysis—the process of splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. In a fuel cell, we’re essentially running that process backward to generate power.

Why Is This Reaction So Efficient?

One of the biggest advantages of fuel cells is their high efficiency. Traditional internal combustion engines—like those in gasoline cars—convert only about 20–30% of the fuel’s energy into useful work. The rest is lost as heat. In contrast, hydrogen fuel cells can convert 40–60% of the hydrogen’s energy into electricity. When waste heat is captured and used (for heating buildings, for example), the total efficiency can exceed 80%.

This efficiency comes from the direct conversion of chemical energy to electrical energy, bypassing the mechanical steps that cause energy loss in engines. There’s no pistons, no crankshafts, no exhaust—just a quiet, steady flow of electrons.

The Role of the Electrolyte and Membrane

The electrolyte is the unsung hero of the fuel cell. It’s the barrier that separates the anode and cathode while allowing only specific particles—like protons—to pass through. Without it, the reaction wouldn’t work properly, and the cell wouldn’t generate electricity.

Different types of fuel cells use different electrolytes, which determine their operating temperature, efficiency, and applications. The most common type for vehicles and portable devices is the Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) fuel cell. It uses a solid polymer membrane as the electrolyte, which allows protons to move from the anode to the cathode but blocks electrons.

How the PEM Membrane Works

The PEM membrane is made of a special plastic-like material, often Nafion, that becomes conductive when hydrated. It’s designed to let protons (H⁺) pass through but not electrons. This forces the electrons to travel through an external circuit, creating usable electricity.

The membrane must stay moist to function properly. If it dries out, proton conductivity drops, and the fuel cell loses efficiency. That’s why PEM fuel cells often include humidification systems to maintain the right moisture levels.

Other Types of Electrolytes

While PEM is the most common, other fuel cell types use different electrolytes:

– Alkaline Fuel Cells (AFC): Use a liquid potassium hydroxide solution. They were used in NASA’s Apollo missions but are sensitive to carbon dioxide, which can degrade performance.

– Phosphoric Acid Fuel Cells (PAFC): Use liquid phosphoric acid. They operate at higher temperatures (150–200°C) and are used in stationary power plants.

– Molten Carbonate Fuel Cells (MCFC): Use a molten carbonate salt mixture. They run at very high temperatures (600–700°C) and can use natural gas as fuel, making them good for large-scale power generation.

– Solid Oxide Fuel Cells (SOFC): Use a solid ceramic electrolyte. They’re highly efficient and can run on various fuels, including hydrogen, methane, and biogas. But they require high temperatures (800–1000°C), which limits their use in vehicles.

Each type has its strengths and weaknesses, but PEM remains the top choice for transportation due to its fast start-up, compact size, and low operating temperature.

Hydrogen Production: The Source of the Fuel

A fuel cell is only as clean as the hydrogen that powers it. If hydrogen is produced using fossil fuels, the environmental benefits are reduced. That’s why how we make hydrogen matters just as much as how we use it.

Currently, about 95% of hydrogen is produced from natural gas through a process called steam methane reforming (SMR). In this method, methane (CH₄) reacts with high-temperature steam to produce hydrogen and carbon dioxide:

CH₄ + H₂O → CO + 3H₂ (followed by CO + H₂O → CO₂ + H₂)

While this method is efficient and cheap, it releases significant amounts of CO₂—about 10 kg of CO₂ per kg of hydrogen. This “gray hydrogen” isn’t truly sustainable.

Green Hydrogen: The Clean Alternative

The future of hydrogen lies in “green hydrogen”—hydrogen produced using renewable energy. This is done through electrolysis, a process that splits water (H₂O) into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity:

2H₂O → 2H₂ + O₂

When the electricity comes from solar, wind, or hydropower, the process emits no greenhouse gases. The result is clean, renewable hydrogen that can power fuel cells with zero emissions from production to use.

Electrolyzers—the devices that perform electrolysis—are becoming more efficient and affordable. Countries like Germany, Australia, and Japan are investing heavily in green hydrogen infrastructure. For example, the HyDeal Ambition project in Europe aims to produce green hydrogen at scale for under $1.50 per kg by 2030—making it competitive with fossil fuels.

Other Hydrogen Colors

Hydrogen is often described by color to indicate its production method:

– Blue hydrogen: Made from natural gas, but with carbon capture and storage (CCS) to reduce emissions.

– Turquoise hydrogen: Produced via methane pyrolysis, which splits methane into hydrogen and solid carbon (no CO₂).

– Yellow hydrogen: Made using solar power.

– Purple hydrogen: Produced using nuclear energy.

Each has trade-offs, but green hydrogen is the gold standard for sustainability.

Applications of Hydrogen Fuel Cells

Hydrogen fuel cells are versatile and used in a growing number of applications. Their ability to provide long-range, fast refueling, and zero emissions makes them ideal for sectors where batteries fall short.

Transportation

The most visible use of fuel cells is in vehicles. Companies like Toyota (Mirai), Hyundai (NEXO), and Honda have launched hydrogen-powered cars. These vehicles can travel 300–400 miles on a single tank and refuel in under five minutes—far faster than charging an electric car.

Buses and trucks are also adopting fuel cells. For example, the city of Aberdeen in Scotland operates a fleet of hydrogen buses that reduce urban pollution. In the U.S., companies like Nikola and Toyota are developing hydrogen-powered semi-trucks for long-haul freight.

Stationary Power

Fuel cells provide reliable backup power for hospitals, data centers, and remote locations. They can run continuously as long as hydrogen is supplied, making them more dependable than diesel generators. In Japan, over 300,000 homes use residential fuel cell systems called “Ene-Farm,” which generate electricity and heat from natural gas or hydrogen.

Portable and Emergency Power

Small fuel cells power drones, military equipment, and emergency response tools. They’re lighter and last longer than batteries, making them ideal for field operations. For example, the U.S. military uses portable fuel cells to power communication devices in remote areas.

Aerospace and Maritime

NASA has used fuel cells in spacecraft since the 1960s. The Apollo missions and Space Shuttle relied on them for electricity and drinking water. Today, companies like Airbus are developing hydrogen-powered aircraft for commercial flights. In shipping, fuel cells offer a clean alternative to diesel engines for cargo ships and ferries.

Challenges and Future Outlook

Despite their promise, hydrogen fuel cells face several challenges that must be overcome for widespread adoption.

Hydrogen Storage and Transport

Hydrogen is the lightest element and has low energy density by volume. Storing it requires high pressure (700 bar in vehicles), low temperature (as a liquid at -253°C), or advanced materials like metal hydrides. Each method has trade-offs in cost, safety, and efficiency.

Transporting hydrogen is also complex. Pipelines can be used, but they require special materials to prevent leaks and embrittlement. Trucks and ships are currently the main transport methods, but they’re expensive and energy-intensive.

Cost and Infrastructure

Fuel cells are still more expensive than batteries or engines, mainly due to the use of platinum catalysts and specialized membranes. However, costs are falling as manufacturing scales up and new materials are developed.

Hydrogen refueling stations are scarce. As of 2023, there are fewer than 1,000 worldwide, mostly in California, Japan, and Europe. Building a global hydrogen infrastructure will require massive investment—but governments and companies are stepping up.

Safety Concerns

Hydrogen is flammable and can ignite easily. However, it’s also lighter than air and disperses quickly, reducing explosion risk. Modern fuel cell systems include safety features like leak detectors, automatic shutoffs, and reinforced tanks. In fact, hydrogen vehicles have passed rigorous safety tests and are considered as safe as conventional cars.

The Road Ahead

The future of hydrogen fuel cells is bright. Advances in catalysts (like non-platinum materials), membranes, and storage are making them more efficient and affordable. Green hydrogen production is scaling up, and governments are setting ambitious targets. The European Union’s Hydrogen Strategy aims for 40 GW of electrolyzer capacity by 2030. The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act includes tax credits for clean hydrogen.

As renewable energy becomes cheaper and climate goals tighten, hydrogen fuel cells will play a key role in decarbonizing transportation, industry, and power generation.

Conclusion: A Clean Energy Revolution

The chemistry of hydrogen fuel cells is elegant in its simplicity: combine hydrogen and oxygen, produce electricity and water. No combustion. No emissions. Just clean, efficient power. From cars to spacecraft, these devices are proving that a sustainable future is not only possible—it’s already here.

While challenges remain, the pace of innovation is accelerating. With continued investment in green hydrogen, infrastructure, and technology, fuel cells could become a cornerstone of the global clean energy system. Understanding the science behind them helps us appreciate their potential and push for a world powered by hydrogen—one clean electron at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions

How does a hydrogen fuel cell produce electricity?

A hydrogen fuel cell generates electricity through an electrochemical reaction between hydrogen and oxygen. Hydrogen is split into protons and electrons at the anode, and the electrons flow through a circuit to create current, while protons move to the cathode to form water.

Are hydrogen fuel cells really emission-free?

Yes, at the point of use, fuel cells emit only water and heat. However, the environmental impact depends on how the hydrogen is produced. Green hydrogen, made with renewable energy, is truly emission-free.

What are the main types of hydrogen fuel cells?

The most common types include Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM), Alkaline (AFC), Phosphoric Acid (PAFC), Molten Carbonate (MCFC), and Solid Oxide (SOFC) fuel cells. PEM is best for vehicles due to its low temperature and fast response.

How efficient are hydrogen fuel cells compared to engines?

Fuel cells are much more efficient than internal combustion engines. They convert 40–60% of hydrogen’s energy into electricity, compared to 20–30% for gasoline engines. With heat recovery, efficiency can exceed 80%.

Can hydrogen fuel cells be used in homes?

Yes, residential fuel cell systems like Japan’s Ene-Farm generate electricity and heat for homes. They can run on natural gas or hydrogen and reduce reliance on the grid.

What are the biggest challenges for hydrogen fuel cells?

Key challenges include high costs, limited hydrogen infrastructure, storage difficulties, and the need for sustainable hydrogen production. However, technology and policy are rapidly addressing these issues.