Hydrogen refueling stations are emerging as a clean alternative to gas stations, but widespread replacement remains unlikely in the near term. While hydrogen offers zero-emission potential, high costs, limited infrastructure, and technological hurdles slow adoption. Gas stations will likely coexist with hydrogen for decades.

Key Takeaways

- Hydrogen fuel is clean but expensive: Producing, storing, and transporting hydrogen remains costly compared to gasoline, limiting rapid adoption.

- Infrastructure is still in early stages: As of 2024, fewer than 1,000 hydrogen refueling stations exist globally, mostly in California, Japan, and parts of Europe.

- Fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs) are niche: Only a few thousand FCEVs are on the road worldwide, far fewer than battery electric vehicles (BEVs).

- Hydrogen excels in heavy transport: Trucks, buses, and ships may adopt hydrogen faster than passenger cars due to longer range and faster refueling.

- Government support is critical: Subsidies, tax incentives, and policy mandates are driving early growth in key markets like South Korea and Germany.

- Gas stations aren’t disappearing soon: Traditional fueling will dominate for decades, especially in rural and developing regions.

- Hybrid future is more likely: A mix of electric, hydrogen, and conventional fuels will coexist, tailored to regional needs and vehicle types.

📑 Table of Contents

- The Rise of Hydrogen: A Clean Fuel on the Horizon

- How Hydrogen Refueling Stations Work

- The Current State of Hydrogen Infrastructure

- Hydrogen vs. Gasoline: A Head-to-Head Comparison

- Where Hydrogen Is Gaining Ground

- The Role of Government and Industry

- The Future: Coexistence, Not Replacement

- Conclusion

The Rise of Hydrogen: A Clean Fuel on the Horizon

Imagine pulling up to a fueling station, connecting a nozzle, and refueling your car in under five minutes—just like gasoline. But instead of emitting carbon dioxide, your vehicle releases only water vapor. That’s the promise of hydrogen fuel cell vehicles (FCEVs), and it’s no longer science fiction. Hydrogen refueling stations are beginning to appear in select cities around the world, offering a glimpse into a cleaner transportation future.

Hydrogen has long been hailed as a potential game-changer for decarbonizing transportation. When used in a fuel cell, hydrogen combines with oxygen to produce electricity, powering an electric motor. The only byproduct? Pure water. This makes hydrogen an attractive alternative to fossil fuels, especially as governments and industries push toward net-zero emissions. But despite the environmental benefits, the question remains: will hydrogen refueling stations actually replace traditional gas stations?

The answer isn’t a simple yes or no. While hydrogen holds promise, especially for certain types of vehicles and industries, it faces significant challenges that prevent it from overtaking gasoline anytime soon. From high production costs to limited infrastructure, the road to hydrogen dominance is long and winding. Still, progress is being made—and in some sectors, hydrogen is already gaining traction.

How Hydrogen Refueling Stations Work

Visual guide about Will Hydrogen Refueling Stations Replace Traditional Gas Stations?

Image source: hydrogenfuelnews.com

To understand whether hydrogen stations can replace gas stations, it helps to know how they function. Hydrogen refueling stations, also known as hydrogen fueling stations or H2 stations, are designed to deliver compressed hydrogen gas to vehicles equipped with fuel cells. The process is surprisingly similar to filling up with gasoline—just faster and cleaner.

The Refueling Process

When you pull up to a hydrogen station, you’ll typically find a dispenser that looks much like a gas pump. After verifying your vehicle’s compatibility, you connect a nozzle to the fuel inlet. The station then pumps high-pressure hydrogen—usually at 350 or 700 bar—into the vehicle’s onboard storage tanks. Most FCEVs can be fully refueled in three to five minutes, matching or even beating the speed of gasoline refueling.

This quick turnaround is one of hydrogen’s biggest advantages over battery electric vehicles (BEVs), which can take 30 minutes to several hours to recharge, depending on the charger type. For drivers who need to get back on the road fast—like delivery trucks or long-haul freight drivers—hydrogen offers a compelling alternative.

Types of Hydrogen Stations

Not all hydrogen stations are created equal. There are two main types:

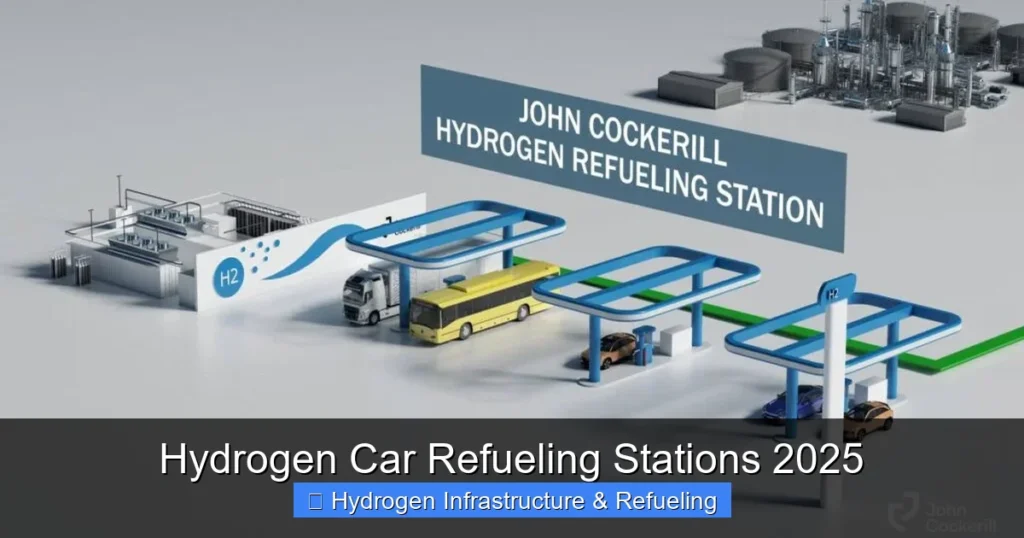

- Centralized stations: These are large facilities that receive hydrogen via pipeline or tanker trucks from off-site production plants. They’re common in regions with established hydrogen supply chains, like California and Japan.

- On-site production stations: These stations generate hydrogen directly on location, often using electrolysis—splitting water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. If the electricity comes from renewable sources like wind or solar, this method produces “green hydrogen,” which is fully carbon-free.

On-site stations reduce transportation costs and emissions but require more space and upfront investment. They’re ideal for areas with abundant renewable energy and limited hydrogen delivery infrastructure.

Safety and Storage

Hydrogen is highly flammable and lighter than air, which raises safety concerns. However, modern hydrogen stations are designed with multiple safety features, including leak detection systems, automatic shut-off valves, and flame arrestors. Vehicles also have reinforced tanks made of carbon fiber that can withstand high pressures and impacts.

In fact, studies show that hydrogen vehicles are as safe—or safer—than gasoline-powered cars in crashes. The gas disperses quickly into the atmosphere, reducing the risk of fire compared to liquid fuels that can pool and ignite.

The Current State of Hydrogen Infrastructure

Despite the technological promise, hydrogen refueling infrastructure remains in its infancy. As of 2024, there are fewer than 1,000 hydrogen refueling stations worldwide. To put that in perspective, there are over 150,000 gas stations in the United States alone.

Global Distribution

The majority of hydrogen stations are concentrated in a handful of countries:

- United States: Over 60 stations, almost all in California. The state has invested heavily in hydrogen infrastructure as part of its zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate.

- Japan: Around 160 stations, supported by government initiatives and partnerships with automakers like Toyota and Honda.

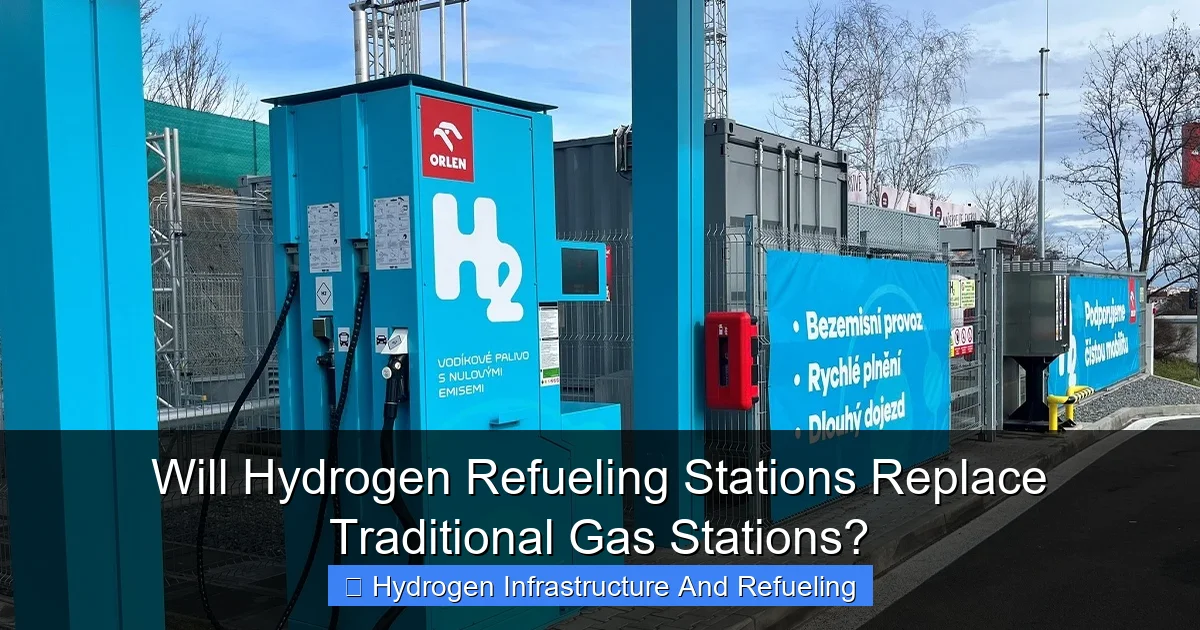

- Germany: More than 100 stations, part of a national hydrogen strategy aimed at decarbonizing industry and transport.

- South Korea: Approximately 200 stations, with aggressive plans to expand to 1,200 by 2040.

- China: Rapidly growing, with over 300 stations built in the past five years, primarily for buses and trucks.

These numbers may seem small, but they represent significant progress. In 2015, there were fewer than 100 hydrogen stations globally. The growth rate is encouraging, but it’s still far from the scale needed to challenge gasoline.

Challenges to Expansion

Building a hydrogen refueling network isn’t just about installing pumps. It requires a complete supply chain, from production to distribution. And that’s where the biggest hurdles lie.

First, hydrogen production is energy-intensive. Most hydrogen today is made from natural gas through a process called steam methane reforming, which emits carbon dioxide. This “gray hydrogen” undermines the environmental benefits. While “green hydrogen” from renewable energy is cleaner, it’s also much more expensive—currently two to three times the cost of gray hydrogen.

Second, transporting hydrogen is difficult. It’s a small, light molecule that can leak easily and requires high-pressure tanks or cryogenic temperatures to store as a liquid. Pipelines exist in some industrial areas, but building new ones is costly and faces regulatory and public acceptance challenges.

Third, demand is low. With only a few thousand FCEVs on the road, there’s little economic incentive for private companies to invest in hydrogen stations. It’s a classic chicken-and-egg problem: without more stations, consumers won’t buy FCEVs; without more FCEVs, companies won’t build stations.

Hydrogen vs. Gasoline: A Head-to-Head Comparison

To assess whether hydrogen can replace gasoline, it’s helpful to compare the two side by side across key factors: cost, convenience, environmental impact, and scalability.

Cost

Hydrogen fuel is significantly more expensive than gasoline. In California, where most U.S. hydrogen stations are located, the average price is around $16 per kilogram. A typical FCEV like the Toyota Mirai has a range of about 400 miles and uses roughly 1 kg of hydrogen per 70 miles. That means a full tank costs about $90—compared to $60–$80 for a gasoline-powered car with similar range.

Production costs are a major factor. Green hydrogen currently costs $4–$6 per kg, while gray hydrogen is $1–$2 per kg. Gasoline, by contrast, costs less than $1 per liter to produce (not including taxes and distribution). Until hydrogen production becomes cheaper—through scaling, innovation, or cheaper renewables—it will struggle to compete on price.

Convenience

Here, hydrogen has a clear edge. Refueling takes minutes, not hours. You don’t need to plug in or wait for a charge. For drivers who value time—especially commercial fleets—this is a huge advantage.

But convenience also depends on availability. If you live outside a major city or travel long distances, finding a hydrogen station can be nearly impossible. Gas stations, on the other hand, are everywhere. Even in rural areas, you’re rarely more than 20 miles from a pump.

Environmental Impact

Hydrogen wins on emissions—if it’s green. When produced using renewable energy, hydrogen is truly zero-emission from well to wheel. But if it’s made from fossil fuels, the carbon footprint can be worse than gasoline.

A 2021 study by the International Council on Clean Transportation found that gray hydrogen can produce up to 20% more lifecycle emissions than diesel. Only green hydrogen offers a clear environmental benefit.

Gasoline, of course, is a major contributor to climate change. Burning one gallon emits about 8.9 kg of CO₂. Over a vehicle’s lifetime, that adds up to tens of tons of greenhouse gases.

Scalability

Gasoline infrastructure is mature and deeply embedded. Refineries, pipelines, tankers, and gas stations form a global network that’s hard to replicate. Transitioning to hydrogen would require rebuilding much of this system from scratch.

Hydrogen, by contrast, is still in the pilot phase. While it’s scalable in theory, it would need massive investment—estimated in the hundreds of billions of dollars—to reach nationwide coverage.

Where Hydrogen Is Gaining Ground

While passenger cars may not be the fastest adopters of hydrogen, other sectors are embracing the technology.

Heavy-Duty Transportation

Trucks, buses, and trains are prime candidates for hydrogen. These vehicles travel long distances, carry heavy loads, and need to refuel quickly. Battery electric trucks are emerging, but their large batteries reduce payload and require long charging times.

Hydrogen fuel cell trucks, like those being developed by Hyundai, Toyota, and Nikola, offer a solution. They can travel 500–800 miles on a single tank and refuel in 15–30 minutes. Several pilot programs are underway, including a hydrogen truck corridor between Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

Public Transit and Fleets

Cities are turning to hydrogen buses to reduce urban pollution. London, for example, operates a fleet of hydrogen double-decker buses. In China, thousands of hydrogen buses are in service, supported by government subsidies.

Fleet operators—like delivery companies and logistics firms—are also testing hydrogen vehicles. Amazon and Walmart have invested in hydrogen-powered forklifts and delivery vans, citing faster refueling and longer range as key benefits.

Maritime and Aviation

Shipping and aviation are hard to decarbonize with batteries due to energy density limitations. Hydrogen, especially in the form of liquid hydrogen or ammonia, is being explored as a fuel for ships and planes.

Companies like Airbus are developing hydrogen-powered aircraft, with test flights expected in the late 2020s. While still experimental, these efforts show hydrogen’s potential beyond road transport.

The Role of Government and Industry

The future of hydrogen refueling stations depends heavily on policy and investment.

Government Support

Countries leading in hydrogen have strong government backing. South Korea’s Hydrogen Economy Roadmap aims to create a hydrogen society by 2050, with $20 billion in public and private investment. Germany’s National Hydrogen Strategy includes €9 billion in funding for production, infrastructure, and research.

In the U.S., the Inflation Reduction Act (2022) includes tax credits for clean hydrogen production, potentially reducing costs by 50% or more. California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard also incentivizes hydrogen use in transportation.

These policies are crucial for kickstarting the market. Without them, private investment would be too risky.

Industry Collaboration

Automakers, energy companies, and tech firms are forming partnerships to advance hydrogen. Toyota and Shell have co-developed hydrogen stations in California. Hyundai has partnered with Ineos to supply hydrogen trucks in Europe.

Oil and gas giants like BP and TotalEnergies are also investing in hydrogen, seeing it as a way to diversify their energy portfolios. BP plans to build a large green hydrogen plant in the UK by 2030.

These collaborations help share costs and accelerate deployment, but they also highlight the scale of the challenge. Building a hydrogen economy requires coordination across industries—something that takes time.

The Future: Coexistence, Not Replacement

So, will hydrogen refueling stations replace traditional gas stations? The short answer is: not anytime soon. But they will likely become a significant part of the energy mix—especially for specific applications.

A Multi-Fuel Future

The most realistic scenario is a hybrid transportation ecosystem. Battery electric vehicles will dominate passenger cars in urban areas, where charging infrastructure is growing rapidly. Hydrogen will gain ground in heavy transport, long-haul freight, and regions with abundant renewable energy.

Gas stations won’t disappear overnight. In fact, many are already adapting. Some are adding EV chargers or hydrogen pumps alongside gasoline and diesel. Others are converting to multi-fuel hubs that serve a variety of vehicles.

This transition will take decades. Gasoline will remain dominant in developing countries and rural areas where infrastructure investment is limited. But in cities and industrial corridors, hydrogen and electricity will gradually take over.

Timeline and Projections

Experts predict that hydrogen could supply 10–15% of global transport energy by 2050, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA). That’s a significant share—but still far from replacing gasoline.

By 2030, we may see thousands of hydrogen stations worldwide, primarily in urban centers and along major highways. FCEV sales could reach 1–2 million annually, up from just a few thousand today.

But for hydrogen to truly compete, costs must fall. Green hydrogen needs to reach $2 per kg or less—a target that may be achievable by 2035 with scaling and innovation.

What You Can Do Today

If you’re interested in hydrogen, there are ways to get involved:

- Stay informed: Follow developments in hydrogen technology and policy. News outlets, government reports, and industry publications are good sources.

- Support clean energy: Advocate for renewable energy and green hydrogen in your community. Public pressure can drive policy change.

- Consider your vehicle needs: If you drive long distances or operate a fleet, hydrogen might be worth exploring. For city driving, a BEV may be more practical.

- Plan for the future: Even if hydrogen isn’t here yet, the shift to clean transport is underway. Preparing now can help you adapt later.

Conclusion

Hydrogen refueling stations represent a bold step toward a cleaner, more sustainable transportation system. They offer fast refueling, zero emissions, and the potential to decarbonize sectors that are hard to electrify. But they are not a silver bullet.

High costs, limited infrastructure, and slow vehicle adoption mean hydrogen won’t replace gas stations in the near future. Instead, we’re likely to see a diverse energy landscape where hydrogen, electricity, and fossil fuels coexist—each playing a role based on geography, vehicle type, and economic factors.

The journey to a hydrogen future is just beginning. With continued innovation, investment, and policy support, hydrogen could become a cornerstone of clean transport. But for now, gas stations aren’t going anywhere. The real question isn’t whether hydrogen will replace them—it’s how we can build a smarter, cleaner system that works for everyone.

Frequently Asked Questions

Are hydrogen refueling stations safe?

Yes, hydrogen refueling stations are designed with multiple safety features, including leak detection and automatic shut-off systems. Hydrogen disperses quickly into the air, reducing fire risk compared to gasoline.

How much does it cost to refuel a hydrogen car?

In the U.S., hydrogen fuel costs about $16 per kilogram. A full tank for a typical FCEV costs around $90, which is more expensive than gasoline but offers similar range and faster refueling.

Can I install a hydrogen refueling station at home?

Currently, home hydrogen refueling is not practical due to safety regulations, high costs, and lack of infrastructure. Most hydrogen is dispensed at public or commercial stations.

What vehicles use hydrogen fuel?

Hydrogen is used in fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs) like the Toyota Mirai, Hyundai NEXO, and certain buses and trucks. It’s not compatible with gasoline or battery electric vehicles.

Is hydrogen better for the environment than gasoline?

Only if it’s produced using renewable energy (green hydrogen). Most hydrogen today is made from natural gas and has a higher carbon footprint than gasoline.

Will hydrogen stations be available nationwide?

Unlikely in the near term. Expansion depends on government support, falling production costs, and increased vehicle adoption. Growth will likely be regional, starting in urban and industrial areas.